Britain may have Sir David Attenborough, America might have Michelle Obama, but we, ladies and gentlemen of The Bahamas, have the wonder that is Darold Miller. Now, this is a bit facetious, as we have many a national hero to represent us, but the character (and, sometimes, caricature) that is the sensational Miller is something most Bahamians can appreciate. Blue Curry has, not with little care, immortalised Miller’s image in an artwork for us.

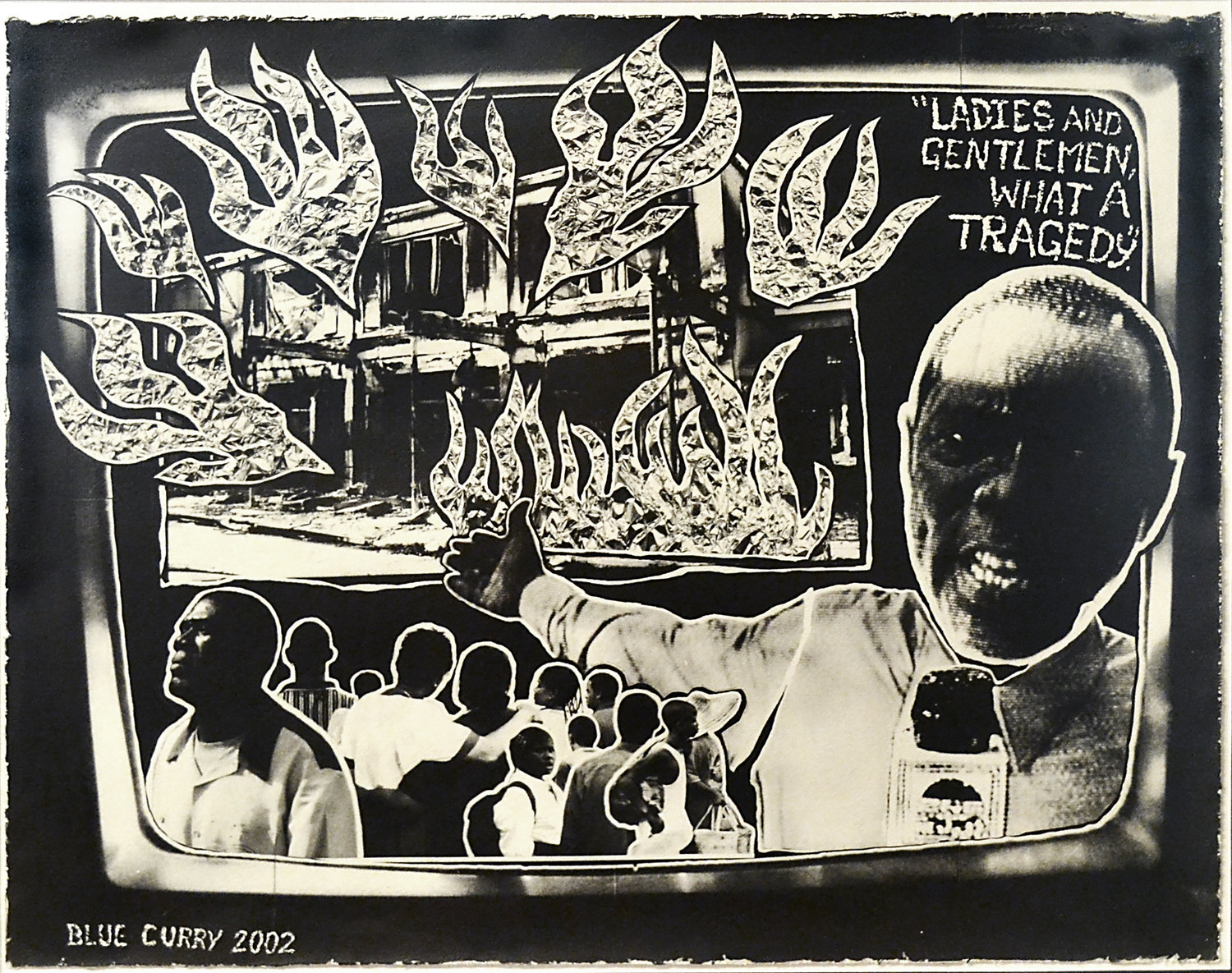

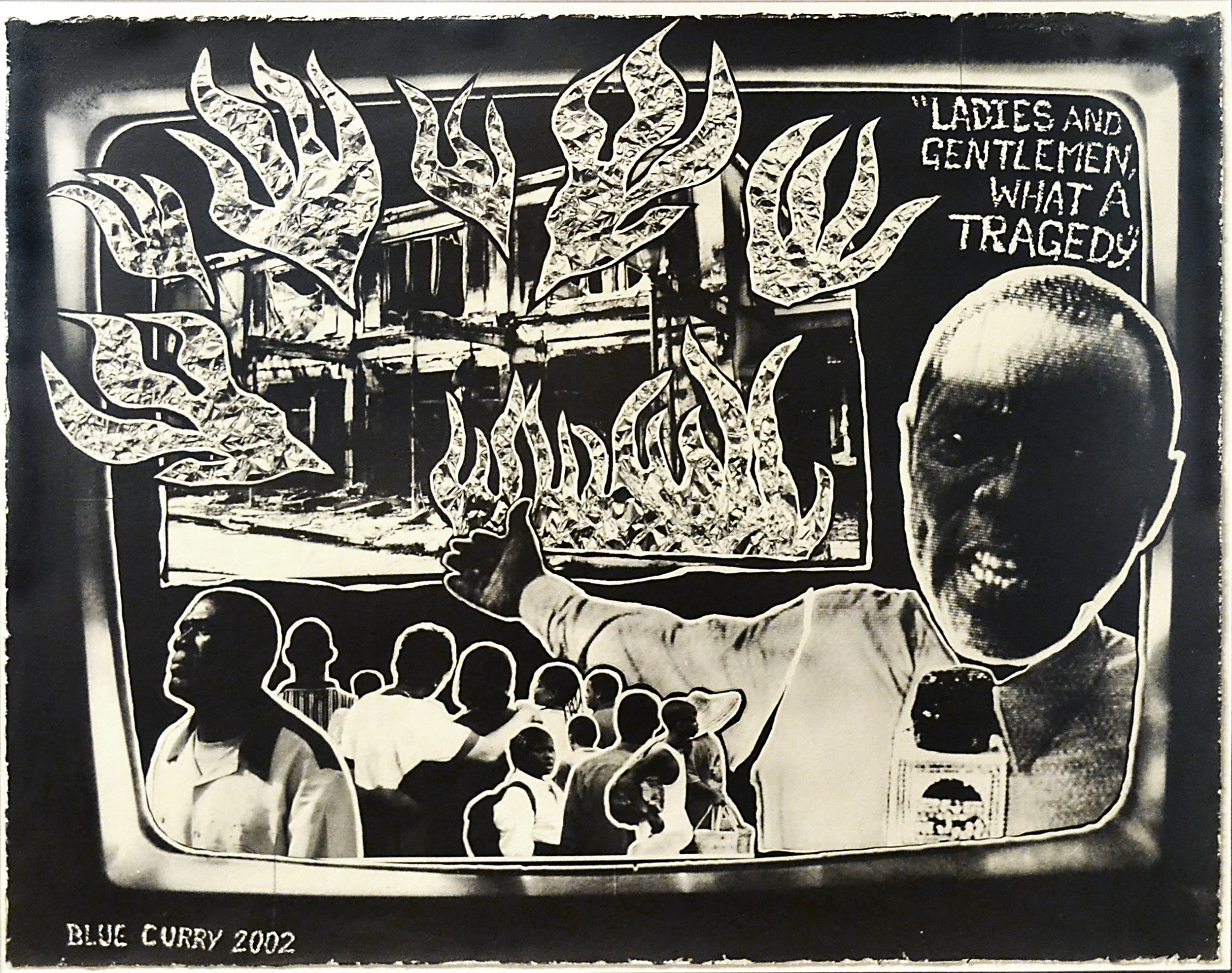

“Bay Street on Fire” (2002), Blue Curry, alternative photography, 24 x 30. Part of the National Collection, as seen in the current Permanent Exhibition “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics”.

For many of us, growing up with, or witnessing the enthusiastic delivery of Miller has been a joy, the start of many laughs and in-jokes for the Bahamian public. Whether you have a Greek surname particularly replete with consonants, or you experience a geographical tidal wave and tsunami of a certain hue, it’s beautiful to have these very specific experiences and characters depicted for us to speak about for generations to come.

Though based primarily in London , Blue Curry still exhibits here at home and throughout the Caribbean. Though he is considered an interdisciplinary contemporary artist who primarily works in sculpture and installation, in his early practice he also produced these ‘alternative photography’ pieces. Curry’s gamut of work usually involves some form of tongue-in-cheek critique of the tourism culture of The Bahamas, but this earlier work which stands in the National Collection from 2002 deals more with public response and representation than tourism as it is. The link is still there of course, as the Straw Market on Bay Street has been well known as a spot for tourist consumerism since the 1800’s, with the particular branding of the space that we know today coming out of a revamp in the 1920’s. Previously, however, the site was used as a market of a different kind, to process enslaved Africans to be sold later at the Vendue House.

“Ladies and gentlemen, what a tragedy” indeed. The lettering is scraped into the black of the paper, rudimentary looking, and the ‘tragedy’ here could easily stand for a number of things: the loss of this historic site, what happened at this site, the loss of livelihood for the vendors – and the straw trade has been going for years. The statement is open-ended, and the presenter, Miller, has his arm outstretched and delivering the message with undeniable fervor, as many of us can remember in seeing his coverage of the awful fire.

The enlargement of his head portrays him in a cartoonish manner, especially when juxtaposed to the bystanders depicted watching the scene – in horror, astonishment, curiosity, or arsonist’s pleasure, we can’t tell – all of whom are of a normal physiology with their bodies in the correct proportions. Knowing that many of us view Miller as a character, Curry is making visual the very thing we all think of when we look on the screen at Miller’s wild gesticulations and empassioned delivery of news.

Where photography and film is often seen to be a ‘true’ depiction of a time or a moment, (which isn’t accurate,, since images are a production of the gaze and minds behind the lens and subject to their own biases) we can take this ‘alternative photography’ to function as just that, an alternative way of looking at images and altering and framing images to tell the story intended by the maker. Most of the bystanders look on to the atrocity, but one turns his back on this. Could this be the peanut seller who started the blaze? Perhaps he is one of the few Bahamians who refused to crowd scenes of accident and incident, as we are usually so wont to do.

His delineation of the work as ‘alternative photography’ also functions in regards to the production of images of the islands for tourist consumption that we know so well – so to have a space that is of such historic value to us, turned into a tourist spectacle, which Curry is then re-interpreting serves as a way to critique the picturesque we have been trading on for over a hundred years. Film and photography, through their associations with depicting a moment in time deal with just that, the idea of time, which Curry plays with here in his use of black and white image.

Curry takes his alternative photography and through this use of black and white we are left to wonder if this real-life historic scene, made fanciful with flames of foil and cartoonish heads, is meant to be taken as historic in its own right. In a way, it is. Art objects serve as a way for us to view how people think of their time, times before them, times imagined, and in “Bay Street on Fire” (2002) Curry has captured a feeling of a moment, in a time capsule of sorts, for generations now to consider.