By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, University of The Bahamas

Centering woman, Tongue could cut, sharp, and leave lasting hurt. Switch does hurt, but that hurt soon gone. Tongue lashes stay decades, as scars welted into minds. Our tongues are inscribed with barbed-wire lyrics that inflict harm on bodies exposed to love and kindness. There shall be little love and less kindness, so you don’t become sof’.

Bahamian women are seen but should not be heard… in this case, the history of invisibility is played on in many of the works in the new incarnation of the Permanent Exhibition at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas(NAGB) called “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean.”

Know ya place. Know ya place, keep ya place. The scathing controls heaped on subject populations from slavery into colonialism is only lessened by a stinging and striking control imposed by respectability and post-colonial structures housed in and around freed bodies. Politics confines, invisibly.

A woman heard in public is worse than a sin. So, why does it seem that art challenges this fixed idea of women by a society that claims to celebrate them, but mostly celebrates their beauty and sexuality as young bodies and then, as youth leaves, their motherhood and grandmotherhood? Their ability to be people in their own right, though always challenged, is always mitigated by their supposed inferiority.

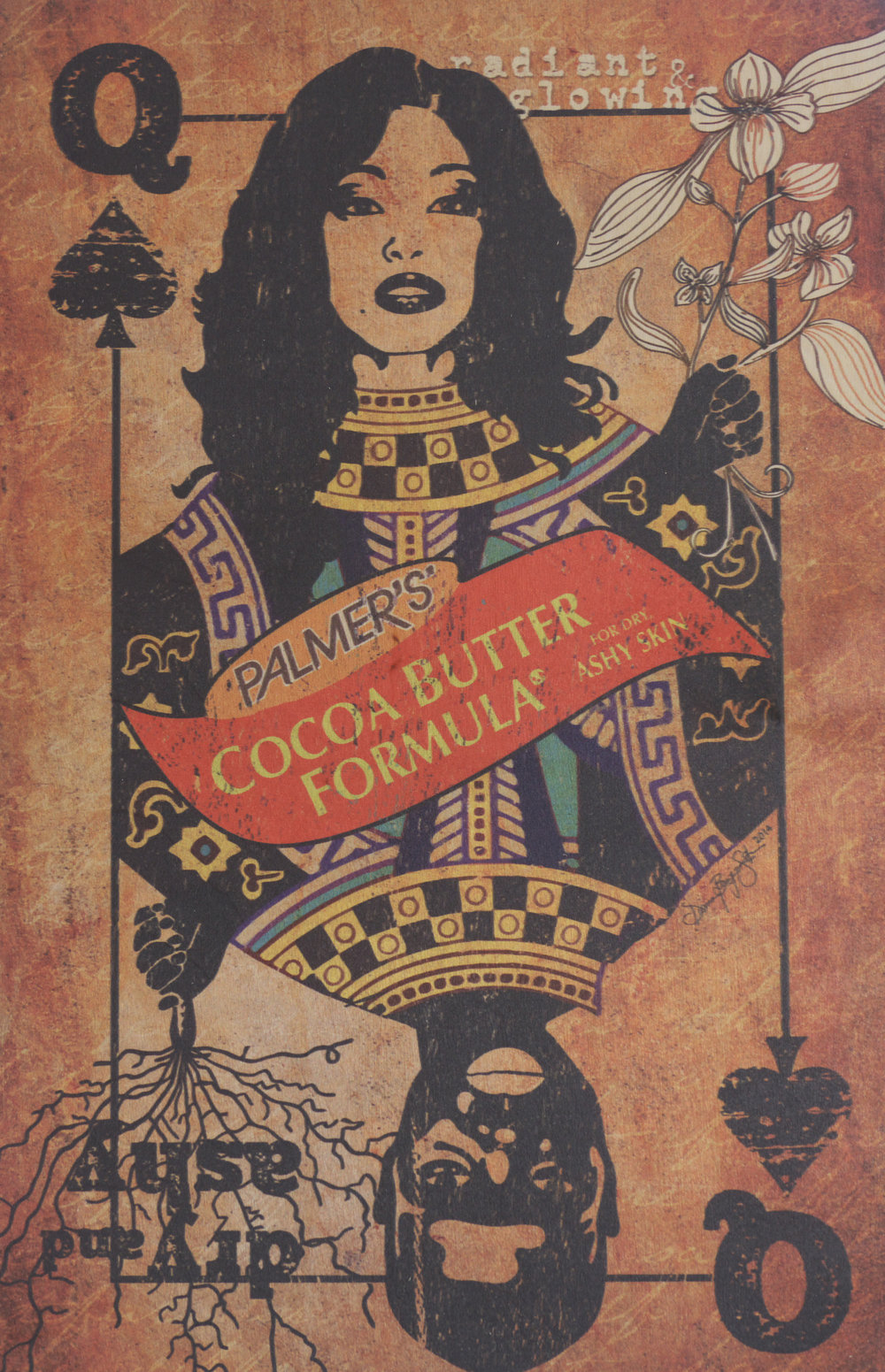

Collage of “Altars/Alters II-IV” (2014). Khia Poitier. Digital media, dimensions variable. Images courtesy of the artist.

Khia Poitier’s Altars/Alters (2014), a digital media work, provides an interesting point of entry into the gallery of women, a pink-walled room of works capturing presentations and concepts of femininity and womanhood in the Bahamian socio-cultural landscape. The work at once plays on the history of the mammy and deconstructs it, though the deconstruction is incomplete and there remains a stinging illustration of black women as wet nurses, objects of desire, work and derision.

Art speaks to the images and imaginings that societies hold. Sometimes, art is a response to or resistance of commonly held beliefs. When Jamaica Kincaid penned “Girl” which appeared in The New Yorker in 1978, she (some say) challenged the Caribbean ideal of femininity—always upheld by women and passed on from mother to daughter. This is the sanctum of machismo and marianismo, an aspect of the female gender role within the confines of Hispanic American folk culture based on the docile virtues of the Virgin Mary. The respectability politics of womanhood is rarely challenged because the struggle is so steep. The climb to respectability—bound up in race, colour and class politics, with a heavy dose of submission for best results—is uphill and mined with pitfalls imposed by the very women who would benefit from its change. Their focus remains affixed to “male provider” myth: should they become more independent, with a full set of rights and social parity, they’d need to go it alone.

Poitier’s Altars/Alters displays the re-contextualised time-lapsed woman: mammy, wife, wet nurse, and stone breaker, who nurses white babies, leaving her own, of which she is not a part, living apart, segregated from them, but providing the very stuff of life for them. Altars/Alters is a (mis)-adventure through the idiosyncrasies of art that collides with history in flashing ways but tells a story of which many young Bahamians are blissfully unaware. When it arises in their lives, they are bemused by it. Society celebrates women’s bodies, hails their virtue, but dismiss their ability/capacity to think as equals to men. Society harnesses their creativity into baby-making and reduces their beauty into a chemicalised pomade that must straighten out coarse kinks to render them culturally and socially acceptable, and a spoonful of bleach to smooth over darkness’s blemishes.

Reading Dionne Benjamin-Smith’s Beauty for Ashes (2014) –a work not exhibited in “Hard Mouth” but shown in the previous Permanent Exhibition “Revisiting: An Eye For the Tropics”–next to Poitier’s digital rendition, focuses on erased agency, yet an agency that belies a foundational role in a society that despises Blackness but cannot survive without it.

Dionne Benjamin-Smith. “Beauty for Ashes”, a series of four collages prepared for the National Exhibition 7 commenting on attempts of normalizing aspects of beauty. Image courtesy of the NAGB.

These artists employ images, historical concepts, and ideals of womanhood to draw attention to the celebration yet derision, the delimitation of possibility and purpose, exacted by writing and drawing over subject bodies. Poitier’s stinging ants, red ants, attacking the white baby being nursed by the mammy–a caricature of Black female identity in the Antebellum American South–who transcends the fixity of time becoming a fixture, though altered to keep pace with a changing idea of Blackness in the 21st century. We can read the flicker of images in two ways, at least, one that the very Blackness enslaved and derided by ‘polite’ and ‘respectable’ society contaminates baby and the other that there is no separation while the red ants’ feast.

The hard mouth woman is always under surveillance, “always eat your food in such a way that it won’t turn someone else’s stomach”; Kincaid’s Girl, (1978). Because you do not control you body, mind and soul, you must always be subservient to the man in the house, though he does little, although he is unable to survive, govern and manage without you.

The Bahamian visual-scape intersects with Kincaid’s juxtaposition of untamed, ruled and regulated respectable femininity, polite society requires of black women—who insist on it and simultaneously undermine and subvert while remaining imprisoned in it. As Kincaid reminds us:

“This is how to behave in the presence of men who don’t know you very well, and this way they won’t recognize the slut immediately I have warned you against becoming; be sure to wash every day, even if it is with your own spit; don’t squat down to play marbles—you are not a boy.” Girl, (1978)

You must always know what kind of woman you want to become and then control it. Understand that society controls women, the image of, the possibility for, success and reputation of. As in silence, there is always a hidden voice, understand that while the colonial frame may capture an ugliness, the desire so deeply etched on Black bodies always comes through the prism of hidden attraction, open repulsion.

“Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean” does so much to smile at and demonstrates how deeply we have traversed and packed away the fears of respectability and the utmost control it has on female bodies. Though society dictates otherwise, women’s bodies are always their own to manage, even while being dominated by the hidden verse of subservience and crippling misogyny. The struggle is hard, but rewards of self-awareness and self-acceptance are huge, as Bahamian women artists continue to work to deconstruct female submissive voices and visions into more honest and transgressive versions of truer, more authentic selves. Herein, self-assurance, sisters, and (her)story stand proudly. Unabashedly.

I am becoming my mother yet I will rise out of the depths of your misery, your sting, your poison, because your prison, your barbed-wired tongue, cannot contain, control, tame the hard mouth gyal from the tongue of the ocean…and so I rise, red ants and all.

The Permanent Exhibition “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean,” is currently on view at the NAGB through June 2019. On Sundays, and every Sunday from 12 – 5pm your NAGB is open and free to all Bahamian citizens and residents.