Currently browsing: Articles

“The Story of “ETA”: Blue/Green Ragged Island” Ideation in Art and Design

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Art and design, though they seem to make strange bedfellows, work hand in glove, and, along with literature, carve out space for exceptional spatial and design shifts that move people into new possibilities. The 2018 iteration of the annual regional collaborative project “Double Dutch” titled “Hot Water,” combines the work of Plastico Fantastico (PF) and Expo 2020 team from University of The Bahamas. The teams spent a week travelling to and from Ragged Island researching what it might look like to rebuild in stronger and more resilient ways in the wake of Hurricane Irma. The project combined students and faculty, as well as members from PF and we interviewed committee and community members and spent hours and then days creating and distilling ideas for the exhibition. What finally stands in the Ballroom of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) is weeks of contact and ideation, with that, a lot of experimentation to see how best to construct and meet new demands.

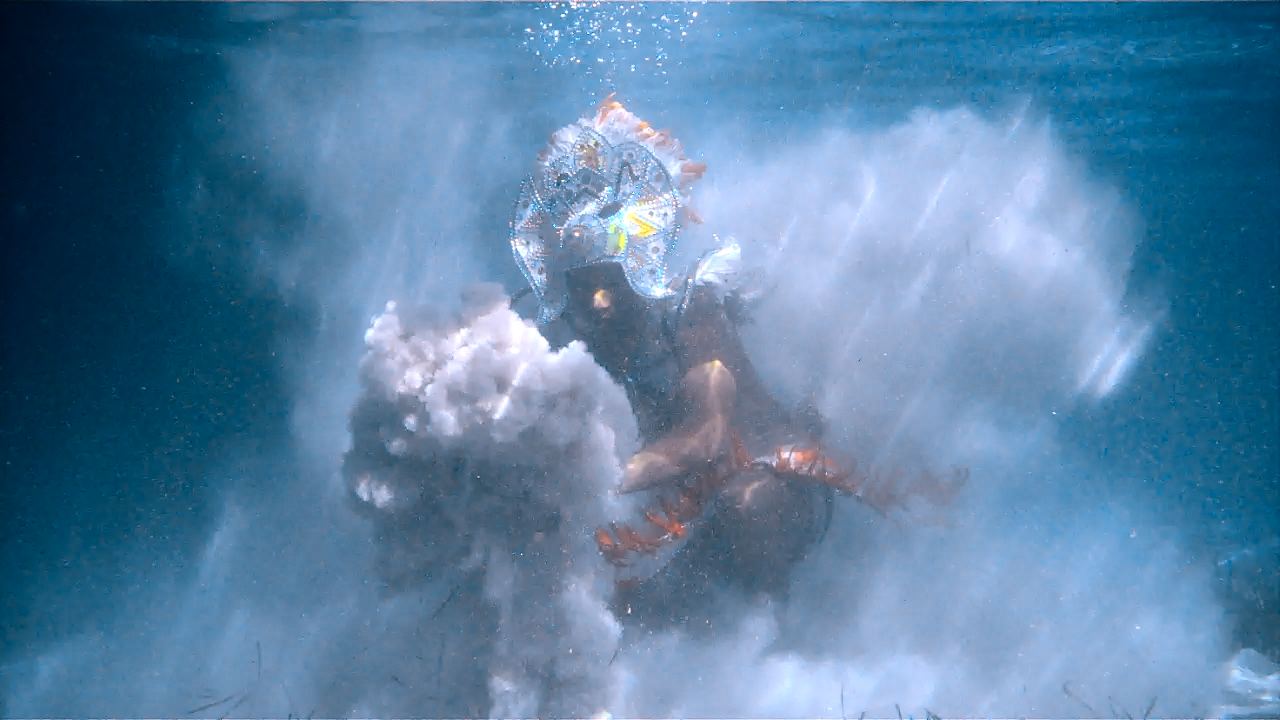

Murky Histories and Futures: “Digging Upward in the Sand” (2018) by Plastico Fantastico

By Natalie Willis. Forward, onward, digging upward in the sand, together. The 2018 “Double Dutch,” the 7th in the series of paired exhibitions, brings us questions on the future, on climate change, on what it means to govern a chain of 700 islands, and on what it means to lose an island’s culture from lack of infrastructure and intervention. “Digging Upward in the Sand” (2018) by the Plastico Fantastico Collective, stirs up these queries, worries, and troubling presents for us.

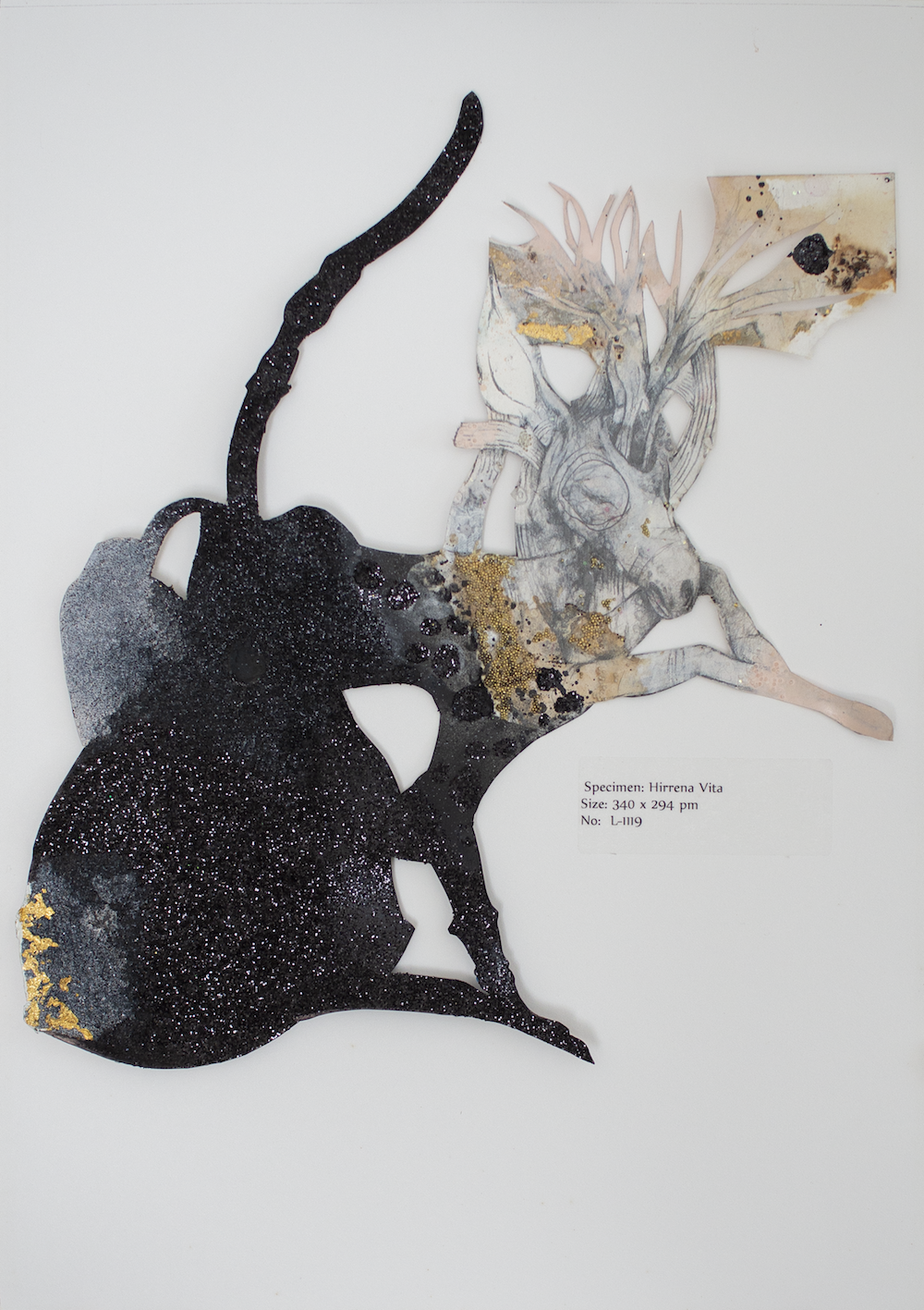

Strange Darknesses: Lavar Munroe’s Sinister Fantasy Creatures

By Natalie Willis. They may appear to be things of fantasy, with their glittering feathered wings, beads, embellishments, and horns adorning those who look to be less than the usual hooved suspects, but Lavar Munroe’s “Specimens” series find their footing in the real world through their presentation, and indeed through their representation. By investigating through fantasy and myth the repercussions and implications of the waves of colonialism on this landscape, first with Columbus, but also alluding to British colonialism with the museum-style classifications and taxonomies of these fair and strange imagined beasts, Munroe’s “specimens” give us a moment to really think beyond the horrific impact on humans and into the broader ecology of The Bahamas.

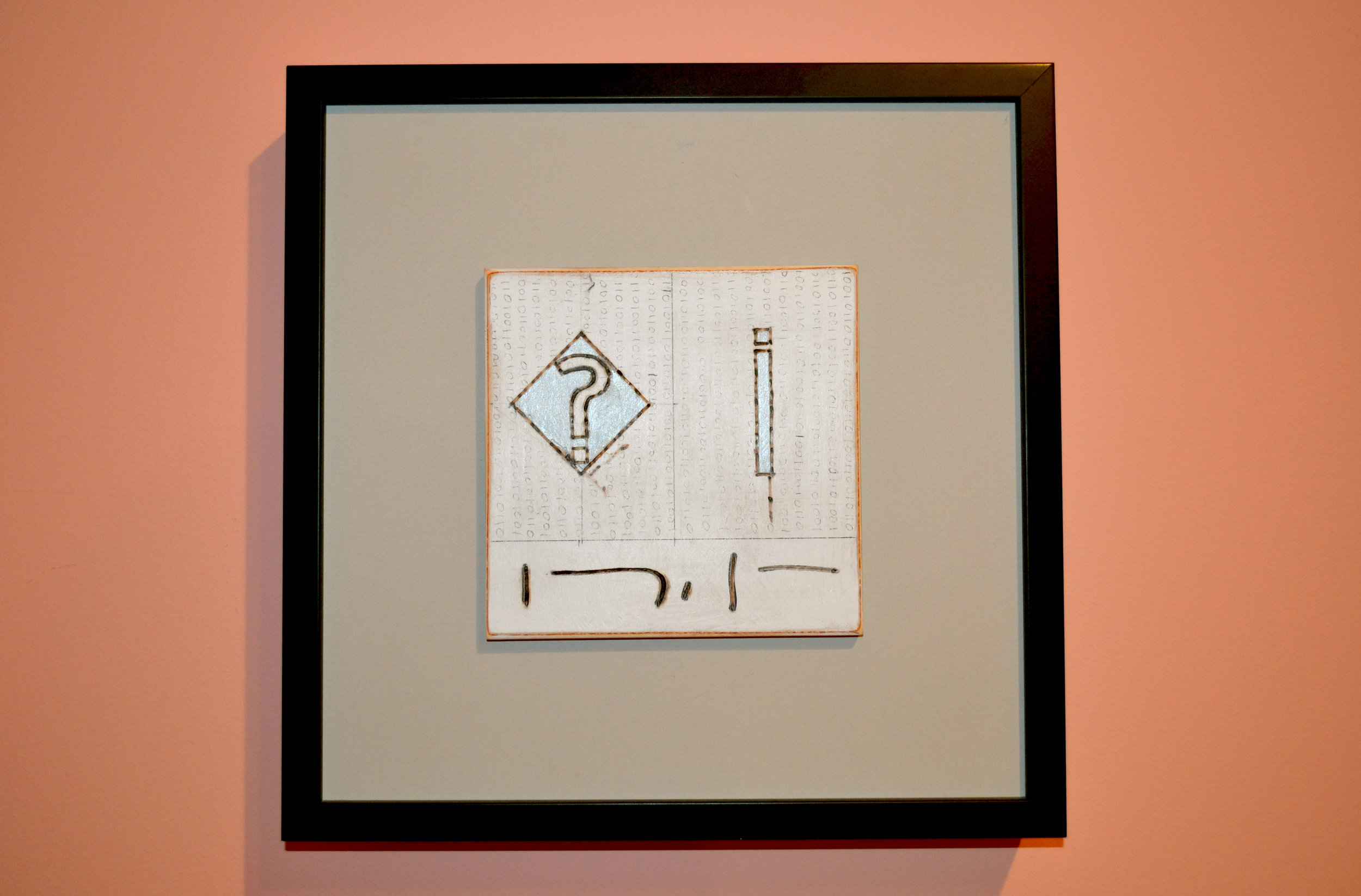

“Who the Hell Do I Think I Am?” (2012) by Margot Bethel

By Natalie Willis. Writer, artist, craftswoman, gallerist, designer, filmmaker, potcake lover, and any other number of titles and markers possible. How do we begin to identify ourselves? Artist is a simple enough term, easily applicable to whoever might be involved. But when we get into craftsman or craftswoman, things get a bit more tricky. Margot Bethel fits into all of the above, in addition to being a master carpenter ( or should we say carpentress?), and her work in the current Permanent Exhibition at the NAGB delves into this idea of gendering and binary, and playfully hints at its futility in the world.

“Burma Road” (c2008) by Maxwell Taylor

By Natalie Willis. Maxwell Taylor is arguably the father of Bahamian art and his social critique of The Bahamas gives us good reason to believe so. Though Brent Malone is often hailed as such, he often referred the title to Taylor and we like to believe this was less to do with Malone’s graciousness (though certainly he was) and more to do with his admiration of the man. Taylor, along with his contemporaries Kendal Hanna and Brent Malone, all served particular functions in helping us to break down what visual culture in The Bahamas, and particularly engagement with it, can and should mean. First and foremost, all were intensely dedicated in perfecting their craft but their approaches to our landscape – physical, social, and spiritual – are as wildly different as the men themselves.

The Aesthetics of Debt: Double Consciousness and Vision in the age new a new modernity

By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett, University of the Bahamas. We usually think of aesthetics in two ways: either the aesthetic pleasure of a work of art or the aesthetics of a period, style or artist. Time has moved on, however, and we are now forced to contemplate differently: the juxtaposition of unrelated ideas/concepts fit into a frame that gives them another meaning or gives us pause. It can be difficult to understand or grapple with the idea of oxymoronic contrast. However, in our daily lives we tend to witness the collapse of modernity in its premise of prosperity struck out by the super prosperous: the contrast between the local and the global.

The art of connectivity: Sinking our roots further down.

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Caribbean peoples have cultural links and subterranean rhizomes–a mass of roots– that connect the region to a larger reality. This is also articulated by Cuban poets and theorists like Nicolas Guillen and Antonio Benítez-Rojo. The ethnomusicologist and anthropologist Fernando Ortiz argues about transculturation and harmonious combined with deeply conflicting existences. We often flatten culture out into its artistic expression, removing any life from it; putting it in a museum and extracting its marrow. We thereby tend to fossilise and remove understanding of culture and its unique link to the place, time and people. So, Guillen, Ortiz and Glissant came up with understandings of culture that transcend limited material understanding. We also remove the multiplicity of experiences and histories from culture because so much of history and culture is limited to the official version as told by the coloniser.

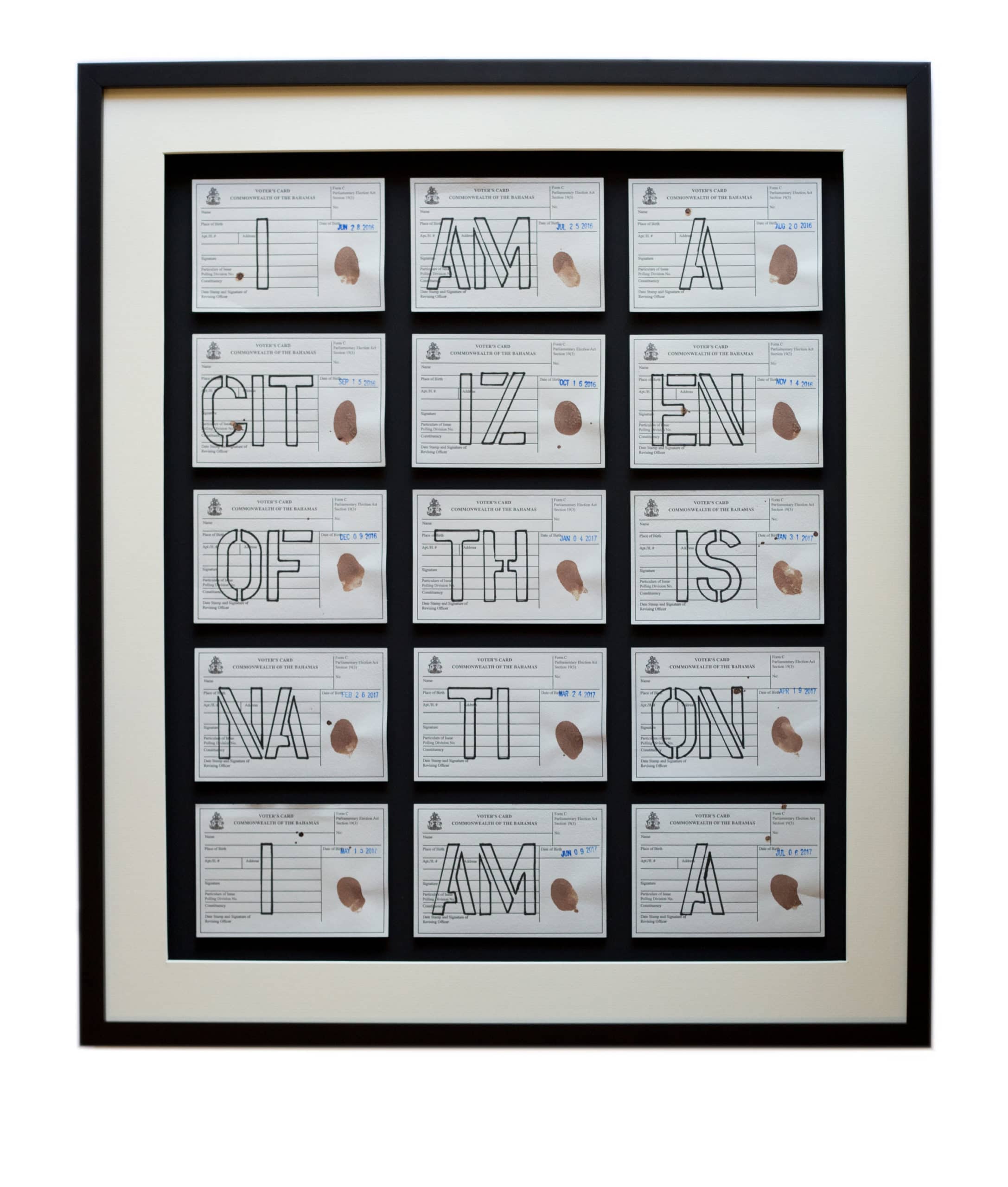

From the Collection: “Cycle of Abuse” (2017) by Sonia Farmer

By Natalie Willis. How does a referendum asking for men and women to be able to both gain rights in passing on citizenship, visibly backed by the government, still manage to fail? And what do we do in the aftermath? Sonia Farmer’s “Cycle of Abuse” (2017) is a paper work, but it is also time based, and the language employed is more than an exclamation, it is social commentary. She declares her status as a Bahamian citizen via text, and as a cisgendered woman she declares her womanhood through the monthly marking of blood upon these ballots. The blood represents not just her femininity and the rights denied her as a Bahamian woman, but also as a symbol of the various ways that violence is continued against women in this country.

The Art of Living in the Tropics, Part Three: Silence

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett, The University of The Bahamas. Culture is the art of living in a place that speaks of experiences, adaptation and resilience. Culture is the unique expression of spatial and temporal identity or vice versa where a people perform life based on their history and geography. As people are increasingly marginalised through the expansion of capitalist desire into the tropics, the art of living there shifts from a national or an indigenous-peoples-based art to art of magazines and design. How do these things meet so that peoples and their cultures can thrive alongside gated out-sourced post-nationalist communities?