By Blake Belcher

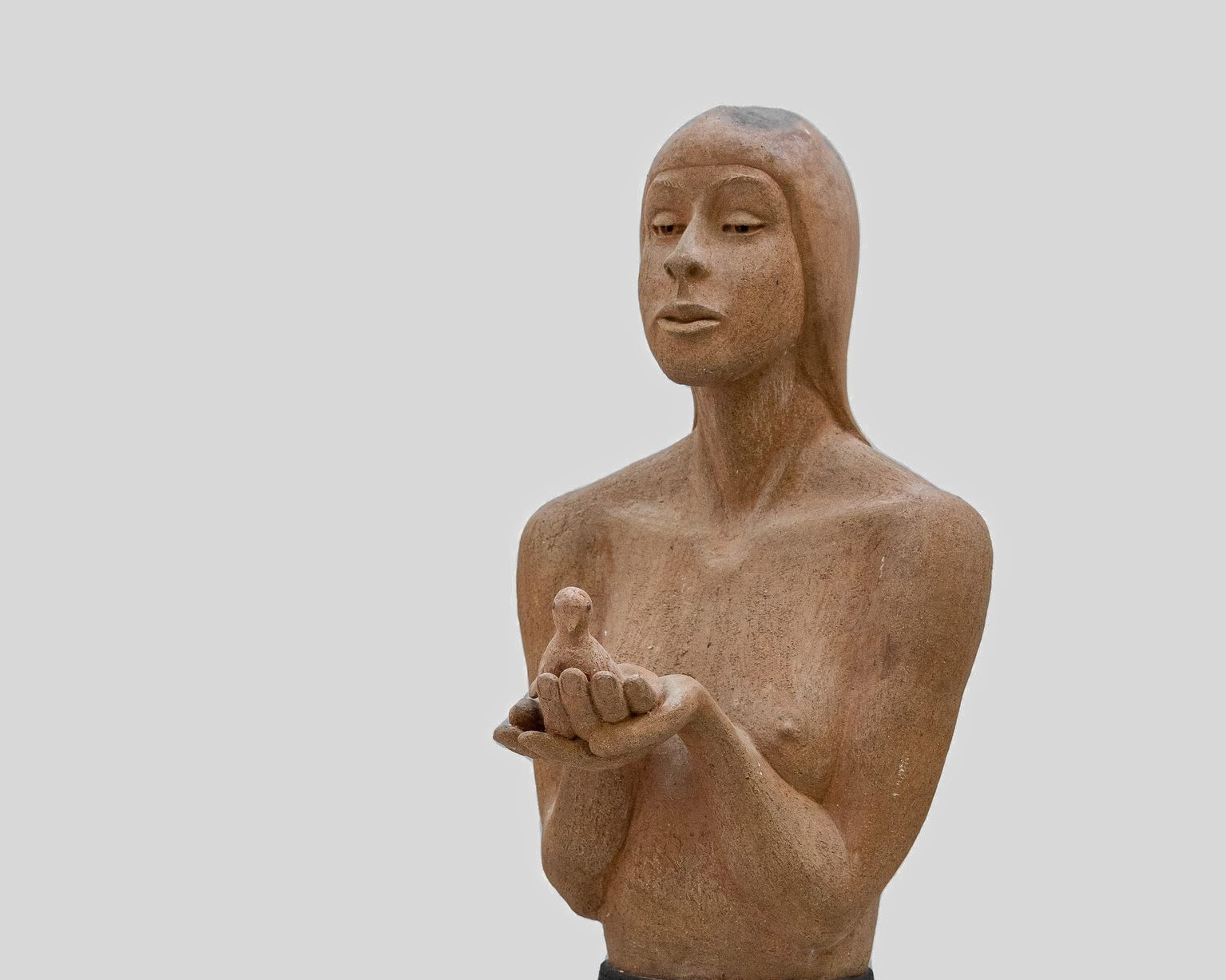

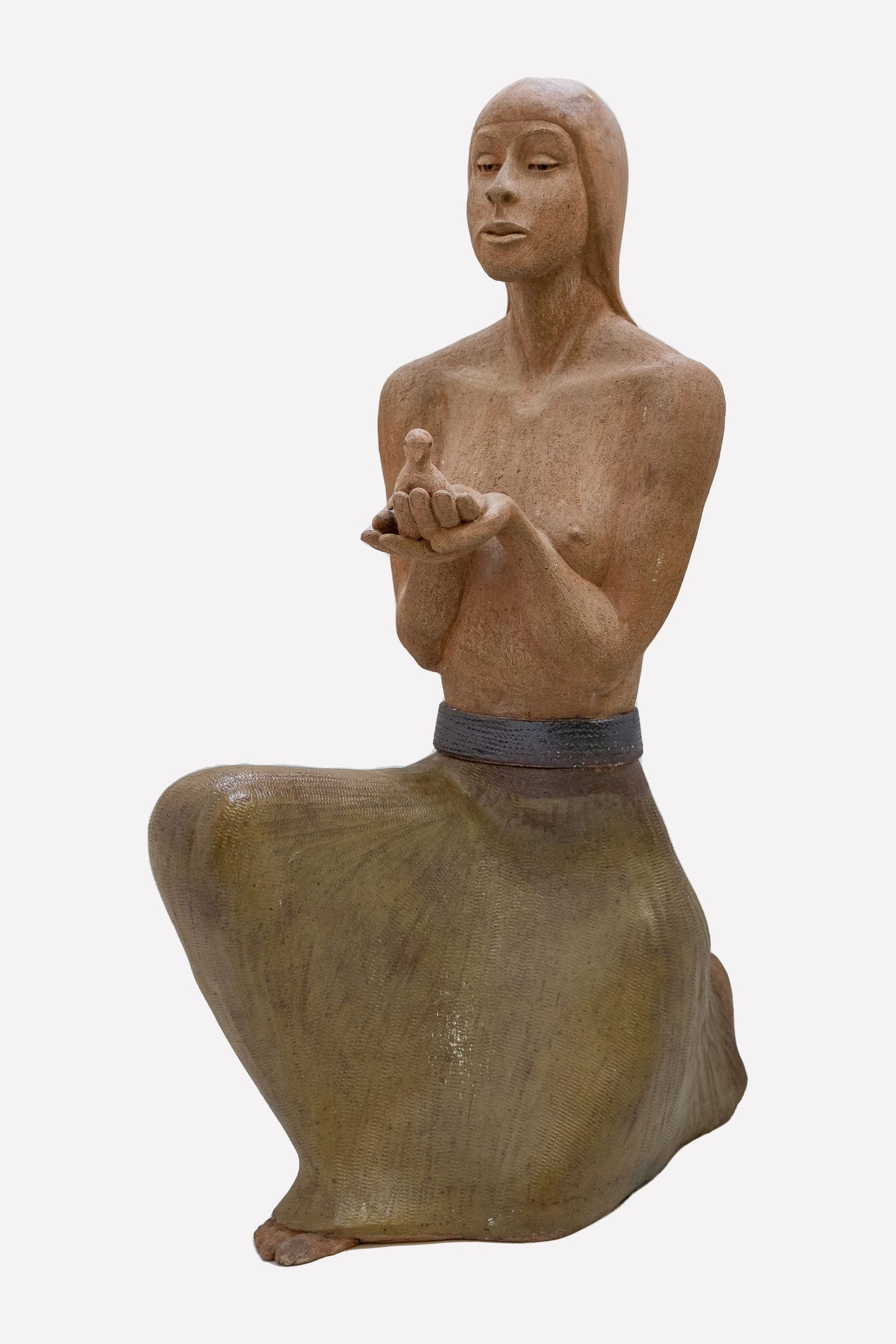

It’s refreshing to see Denis Knight’s Lucayan Woman (c. 2000) in our current permanent exhibition, From the Collection, as it has not been shown at the Gallery for quite some time. The ceramic sculpture depicts an indigenous woman kneeling, her lower half draped in a flowing skirt with ridges, while her upper body remains uncovered. But the surface quality itself is what stands out–her skin, highly textured with flecks of organic material, feels tactile and alive and is evidence of Knight’s preference of using locally sourced clay and low-tech firing without an electric kiln.

He once said every ceramicist should do two things during their lifetime: dig for local clay and fire without electricity. These techniques wouldn’t have been foreign to The Bahamas’ indigenous Lucayan people themselves. Shards of Palmetto ware, a style of Lucayan pottery, are still being recovered today in The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. Though only small fragments, pottery has been historically used to determine timelines, techniques, and ways of life.

Denis Knight (1926–2018) was a British-born artist and carpenter who moved to The Bahamas in 1959 with his first wife, June Knight. They came as teachers and initially settled in Governor’s Harbour, Eleuthera. Knight would go on to run a rehabilitation programme at Sandilands and in the 1960s he joined a group of artists at the Chelsea Pottery in Nassau. In 1989, he moved to Petty’s, Long Island, where he remained with his second wife, Marina Knight, until they both passed in 2018. There, he maintained a small pottery studio fitted with a kiln built for wood firing, partly by necessity due to the lack of electricity on the island. He continued to teach, having left lasting impressions on notable Bahamian ceramicists like Katrina Cartwright and Jessica Colebrooke.

We know that the Bahamian landscape is primarily made up of limestone. It’s dry, porous, and pale – made up of thousands of years of calcified coral, shells, and marine sediment. These materials lack iron, which gives some clays their deep red hue. So where does the red clay come from? According to the Florida Museum of Natural History, this iron-rich dust travels thousands of miles from the Sahara Desert, carried across the Atlantic by wind.

That detail alone feels poetic in a practice that literally sources its medium from the land, and especially so in a region shaped by the violence of forced migration. Clay becomes more than a material, it becomes spiritual – imbued with the memories of the earth and the people who walked on it before us. The Lucayans were wiped out following Columbus’ arrival and the onset of enslavement and foreign diseases. In Lucayan Woman, the earth itself feels charged with this memory. Knight’s sculpture also takes on new meaning when we remember he lived and worked in Long Island (Yuma), one of the first islands reached by Columbus in 1492.

The woman’s skin appears rough, marked with nicks and flecks of organic material, but none of it feels haphazard or violent; it feels reverent. Knight isn’t idealising her; he’s grounding her with his intentional use of material and form.

Set in a cut-out of an old window from the original Villa Doyle, Lucayan Woman becomes a quiet but powerful guardian. She balances the weight of environmental histories and traumas in her body, but cradles a seemingly weightless bird in her hand, perhaps symbolising freedom, peace, or something more spiritual. It’s a gesture towards hope as she holds it gently, never quite letting go.