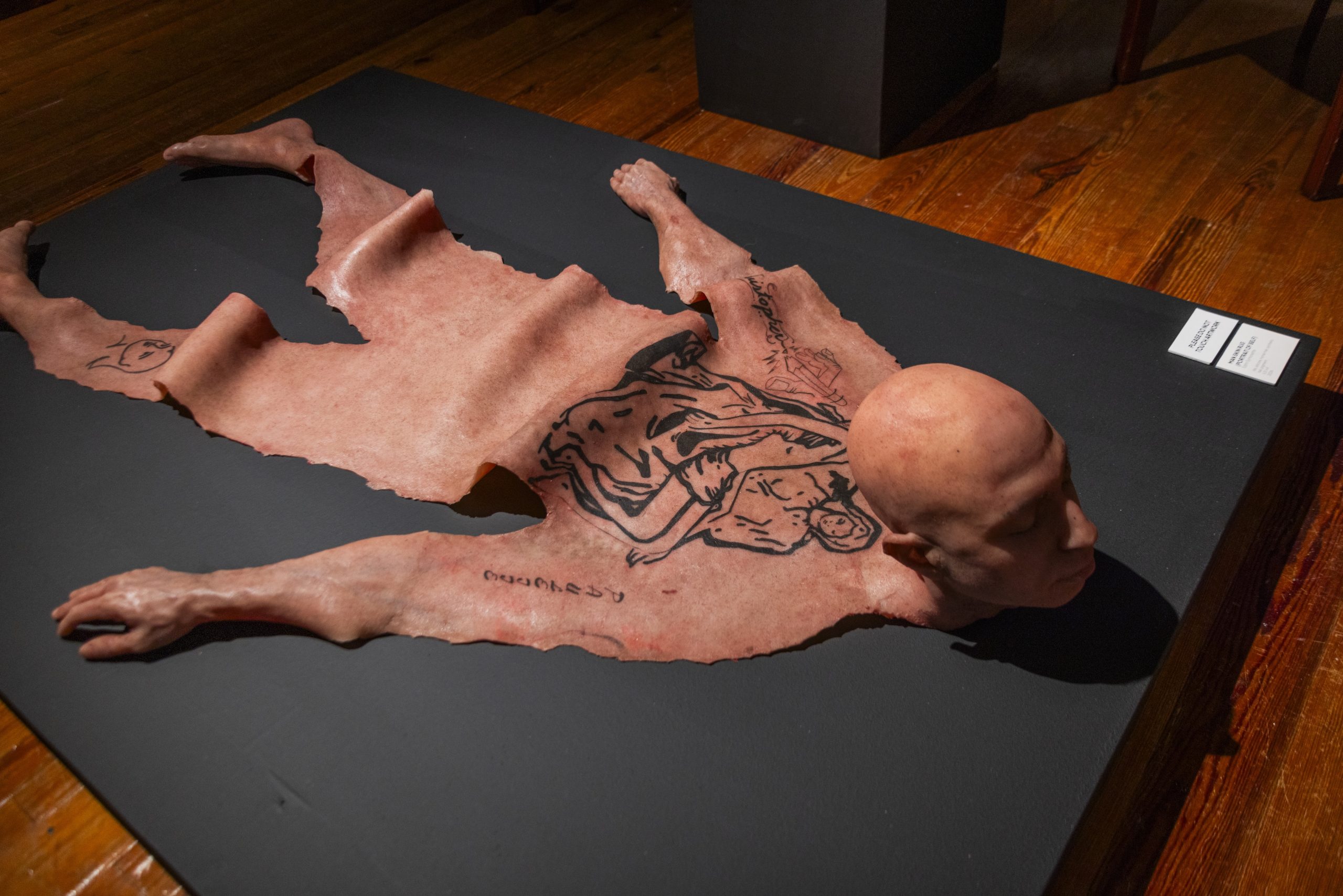

Many artworks compete for your attention in NELEVEN: INTO THE VOID, but none more so than Edrin Symonette’s Man-Skin Rug (2024). The sculpture is a silicone mold of the artist himself, splayed boneless in the middle of the gallery. Since the exhibition’s opening, we have had the joy of experiencing each visitor’s shock (horror? surprise?) at the sculpture. What is a man doing on the floor? And why does he have no bones?

NELEVEN: INTO THE VOID, has been open for about two months now, and as one of its curators, I hope it continues to capture the imaginations of visitors as they come through. Held every two years, the National Exhibition (NE) is a space for contemporary Bahamian artists to show new works that reflect the current climate of our country. It honours ambitious projects that challenge the bounds of artistic practices, dialogue, and social engagement. When my co-curator, Richardo Barrett, and I were considering the theme for the eleventh National Exhibition two years ago, we wanted to highlight the forward movement of contemporary Bahamian art and sought to encourage artists to think about our future as creatives in a nation currently negotiating its survival in a new ecological reality.

Man Skin Rug encapsulates this forward movement in our contemporary art scene. The craftmanship alone is something to be lauded: Edrin molded his own hands, feet, and face using silicone, adding intricate details like veins, tattoos, and naturalistic imperfections of skin using paint. He even went so far as to attach his own hair to the sculpture. The result is an uncanny mold of a man lying on the floor, staring you straight in the eyes as you enter the gallery.

Edrin himself says that he wanted the sculpture to inspire awe and shock the viewer. Despite being a new medium, this sculpture is not unlike his usual practice—Edrin usually plays around with the human form, marrying natural materials with the sculpture that he creates. For NE9, he made Residues of a Colonial Past, which was a sculpture of a man lying in the dirt in our sculpture garden, holding a flower. According to Edrin, he wanted this sculpture to get people talking—especially about colonialism, power, and how we as a Bahamian people need to reconnect with the earth. His motivations have not changed: Man Skin Rug is a critique of black masculinity under the colonial gaze, and steeped in honest emotion: the feeling of being hunted and put on display.

Next to the sculpture, two chairs invite the viewer to sit and touch the silicone skin, evoking immediate, visceral responses. Edrin’s sculpture makes us hyperaware of the historical exploitation of black bodies in colonial spaces. It is a tongue-in-cheek invitation for the visitor to participate in this performance. How do we confront this issue and protect black bodies? Do we simply stare in shock and in horror, or do we dare to look more closely?