By Kelly Fowler, Guest Writer. Maxwell Taylor honours Black Bahamian mothers. As with many things, the concept of motherhood does not always translate neatly or equally cross-culturally. While it is not unusual for a society to have defined gender roles and to encounter expectations based on them, women of marginalised groups tend to face harsher criticism of their lifestyles for not meeting the concept of womanhood or motherhood that is associated with the “ideal.” Naturally, this would lead to feelings of inadequacy and questions of being good or good enough. Bahamian master artist, Maxwell Taylor, delves into this subject matter in much of his work, but his black and white woodcut print on paper entitled Ain’t I A Good Mother?, 2003 is one that addresses Black motherhood specifically.

All posts tagged: Collection

From the Collection: Rembrandt Taylor’s Madonna and Child

The Role of the Arts in Addressing Climate Change

By Blake Fox. Currently on display through June 2, 2019, at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB), the Permanent Exhibition “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean” focuses on how both verbal and visual language have shaped us as a country. One could argue that The Bahamas is a phonocentric culture, meaning speech is given precedence over written or visual work. Because of this emphasis on speech rather than written or visual work, it is no doubt that The Bahamas has a very rich oral culture. While Bahamians rely heavily on oral communication to pass down culture and traditions, visual and written works are just as crucial in communicating cultural beliefs and values in societies. This exhibition highlights Bahamian artwork that serves as a conduit to bridge the gap between our visual and oral culture in The Bahamas.

To Heal We Must Remember: Katrina Cartwright’s power figure uproots the past

By Letitia Pratt. It is a hopeful mission of the African diasporas to heal the ancestral pain that Black peoples have inherited. This healing will only come to us in the process of remembering. One of the primary ways to initiate this process is through the creation and consumption of art, which invites us to remember the past, take stock of the present, and come to terms with the complex histories that influence our current experiences as Black people. This process is especially needed for Black Bahamians, whose past traumas shape how we view ourselves. It is incumbent on our ability to tell truths about our past: we must recall times of slave rebellions, punishments, uprisings and revolts. We must remember the slaves that escaped the tyranny of Lord Rolle of Exuma – only to be recaptured and severely punished – and remember the tragedy of Poor Kate of Crooked Island who died from torture in the stocks for seventeen days. (The Morning Chronicle, 1929). It is these stories we need to remember. These are the stories that shaped our ancestors. These are the traumas we need to heal from. Katrina Cartwright’s Nkisi/Nkondi Figure: Prejudice is the Theory, Discrimination is the Practice, (2012) does just that: It forces us to remember, and it inspires us to heal.

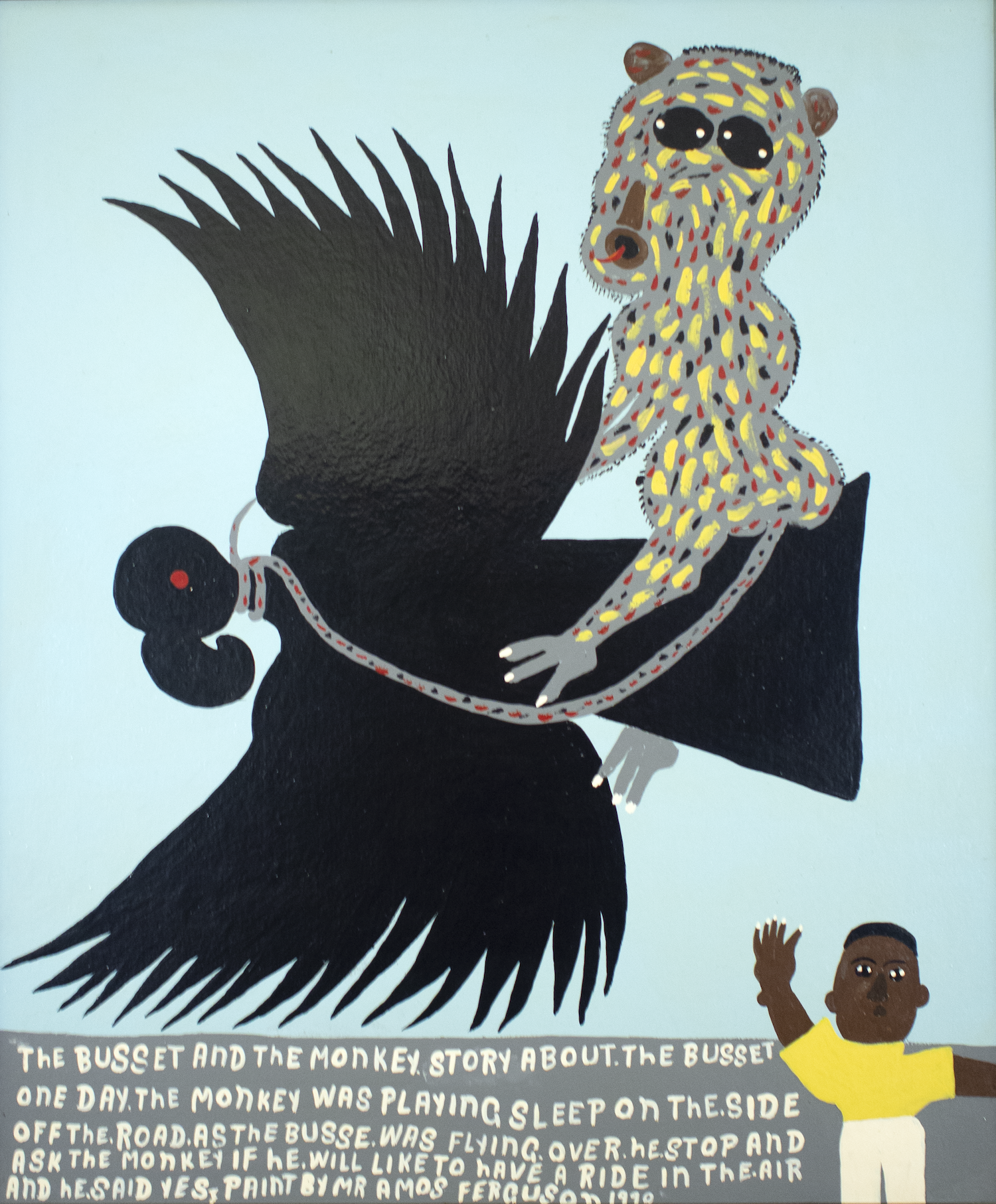

From the Collection: “The Bussett and the Monkey” (1991) by Amos Ferguson

The musical stylings of Bahamian favourite Phil Stubbs, no doubt inspired by the Nat King Cole classic, in this story of the monkey and the buzzard, speak to fable, myth and reality. Amos Ferguson was also quite clearly inspired by this story, as we see in his painting “The Bussett and the Monkey” (1991), currently on display in central Andros as part of the NAGB’s Inter-Island Traveling Exhibition “TRANS: A Migration of Identity”.

UBS Donates a National Treasure: The NAGB and the Bahamian people inherit a Malone masterpiece

By Malika Pryor-Martin. Art is a wondrous thing. It calls forth memories while speaking to our future self. A technician will produce something beautiful. A visionary – something transformative. R. Brent Malone was and accomplished both. He took Junkanoo, what he saw and correctly knew to be a rich, nuanced and electric expression and elevated an (already exquisite) art form, which for too many had been woefully under-appreciated and even mocked. Thanks to a recent act of incredible largesse by UBS, the NAGB was fortunate enough to add to the people’s collection, the National Collection. As Mary Rozell, Global Head UBS Art Collection, shared in a statement, “We are pleased to donate the Brent Malone mural, “Celebration: Spirit of Junkanoo”, originally commissioned for the lobby of the UBS office in Nassau, to the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas to make it available to the broader public in this region.” This massive canvas captures the movement, spirit and fiery intensity of the festival and the NAGB could not be more elated to announce this excellent news.

“Burma Road” (c2008) by Maxwell Taylor

By Natalie Willis. Maxwell Taylor is arguably the father of Bahamian art and his social critique of The Bahamas gives us good reason to believe so. Though Brent Malone is often hailed as such, he often referred the title to Taylor and we like to believe this was less to do with Malone’s graciousness (though certainly he was) and more to do with his admiration of the man. Taylor, along with his contemporaries Kendal Hanna and Brent Malone, all served particular functions in helping us to break down what visual culture in The Bahamas, and particularly engagement with it, can and should mean. First and foremost, all were intensely dedicated in perfecting their craft but their approaches to our landscape – physical, social, and spiritual – are as wildly different as the men themselves.

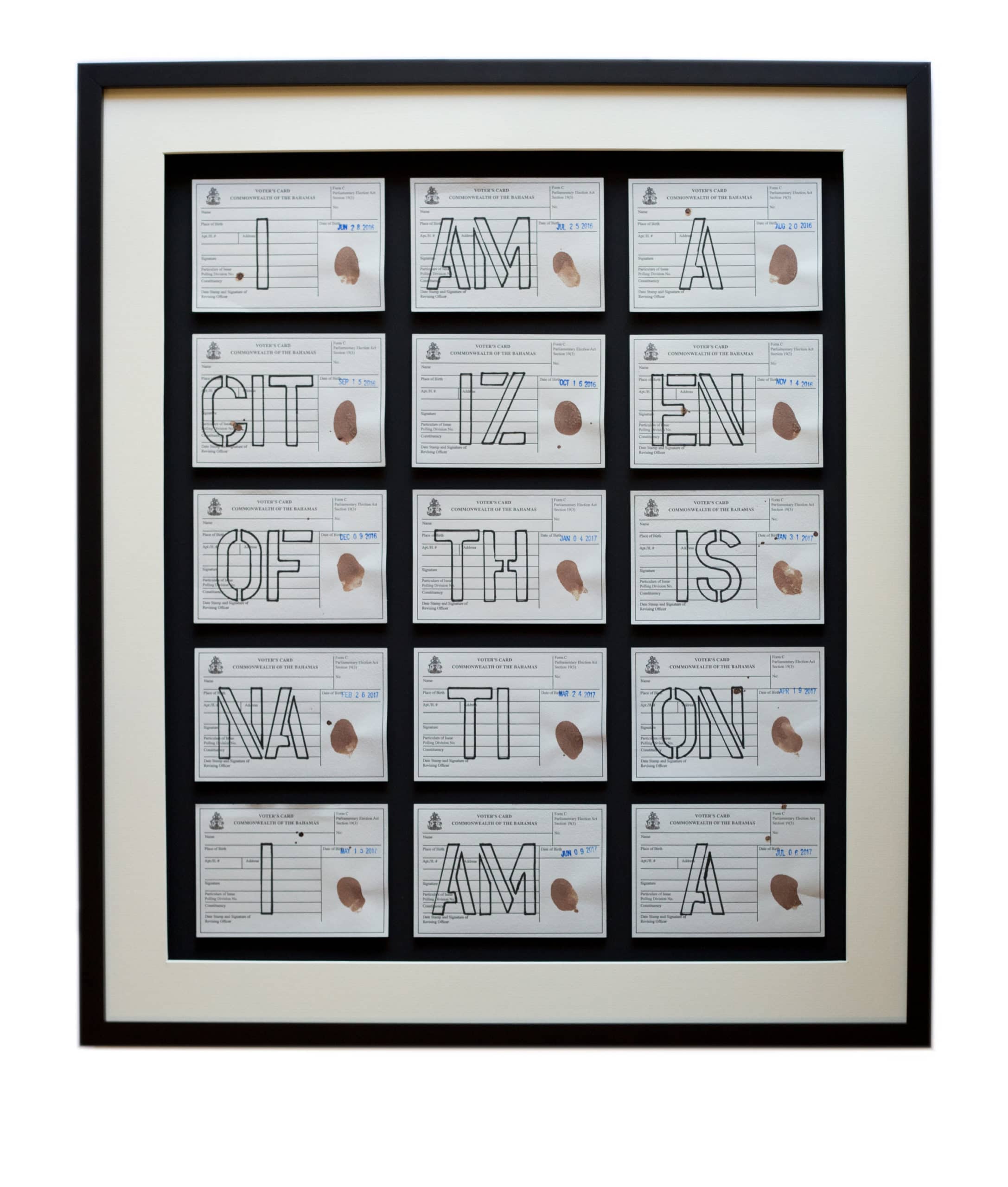

From the Collection: “Cycle of Abuse” (2017) by Sonia Farmer

By Natalie Willis. How does a referendum asking for men and women to be able to both gain rights in passing on citizenship, visibly backed by the government, still manage to fail? And what do we do in the aftermath? Sonia Farmer’s “Cycle of Abuse” (2017) is a paper work, but it is also time based, and the language employed is more than an exclamation, it is social commentary. She declares her status as a Bahamian citizen via text, and as a cisgendered woman she declares her womanhood through the monthly marking of blood upon these ballots. The blood represents not just her femininity and the rights denied her as a Bahamian woman, but also as a symbol of the various ways that violence is continued against women in this country.

From the Collection: “Untitled (Boat Scene)” (c.1920) by James “Doc” Sands

By Natalie Willis

One would imagine this a typical scene along the Nassau coastline in the 1920s, as so much of our history – painful or profitable – was tied to the sea’s comings and goings. “Doc” Sands gives us what appears to be commonplace, but when we situate this image in the context of its time, and in our broader Bahamian history, things begin to take an exciting turn. Bottles and barrels that appeared to be ordinary fare now begin to remind us of prohibition and bootlegging, and the men shaking hands could very well be in the middle of a handoff. Of course, much of the imagery photographed at this time was staged out of necessity – things needed to be reasonably still for a prolonged time for the image to be taken appropriately. Was Sands staging this image of prohibition and illicit-alcohol Nassau at its roaring start?

James Osborne “Doc” Sands was born in 1885 in Rock Sound, Eleuthera, and is noted one of the first Bahamian photographers. The second of six children, his parents moved him to Nassau for what they felt to be a better education, and at age 18 he was handed over the photo studio of his mentor, American photographer Jacob Frank Coonley. Coonley and his contemporary William Henry Jackson (also American) were well known for their work, and now historically for their contributions to building and framing the picturesque, tropical images of The Bahamas at the start of its tourism industry, and Sands took up the mantle at a somewhat tender age.

From the Collection: “Crawfish Lady” (c2000) by Wellington Bridgewater

By Natalie Willis

What does Bahamian fantasy and myth look like? What magic or horror happens when the divides between animal and human seem to dissolve? What then must Wellington Bridgewater have been thinking when he made the “Crawfish Woman” (c2000) who lies on the Southern steps of the NAGB’s Villa Doyle. Was he thinking that this lobster-lady was like the nefarious lusca, sucking water in and out of blue holes to capture unlucky divers and boats with the power of the oceans. Or was she more like the chickcharney, a generally benign beast who, once wronged, would cause you harm.