By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett.

Images can create wealth, or they can be used to create ideas of paradise that serve only to silence those who occupy the place of paradise. Can we begin to use new art or contextualized images to tell a story that sells a place to the world that builds local and resident brands instead of disempowering them?

In the late 90s, there was a noted shift to recapturing the image of empire in England and other parts of the world. The new shift was towards nostalgia of a past that was distant but close, a past that was great, a moment when Britain ruled the waves or was that Britannia, either way, it was the same. The move brought plantation living back to life and reframed race and the encounter differently.

Publications such as Islands Magazine did a few stories that were noteworthy for their re-presentation of what had been cleansed of its stigma and boutiqued by the passage of time and the slippage of memory. One story was on Antigua, and the nostalgia for slavery and the plantation and the other that I found informative was on Cat Island in The Bahamas, the island that time forgot. Both stories rendered the Caribbean this space that was utterly delightful for its backwardness and its charm, of course, the people were lovely and accommodating. We had learned well from our colonial days of submission and suppression.

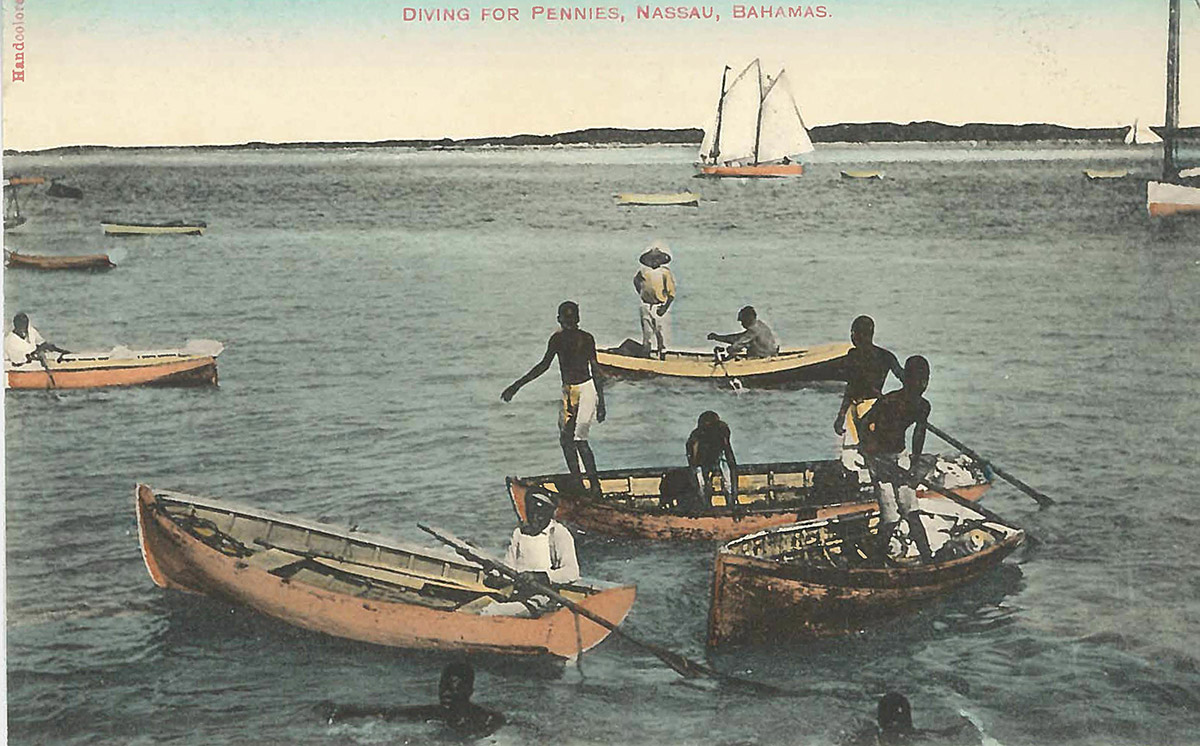

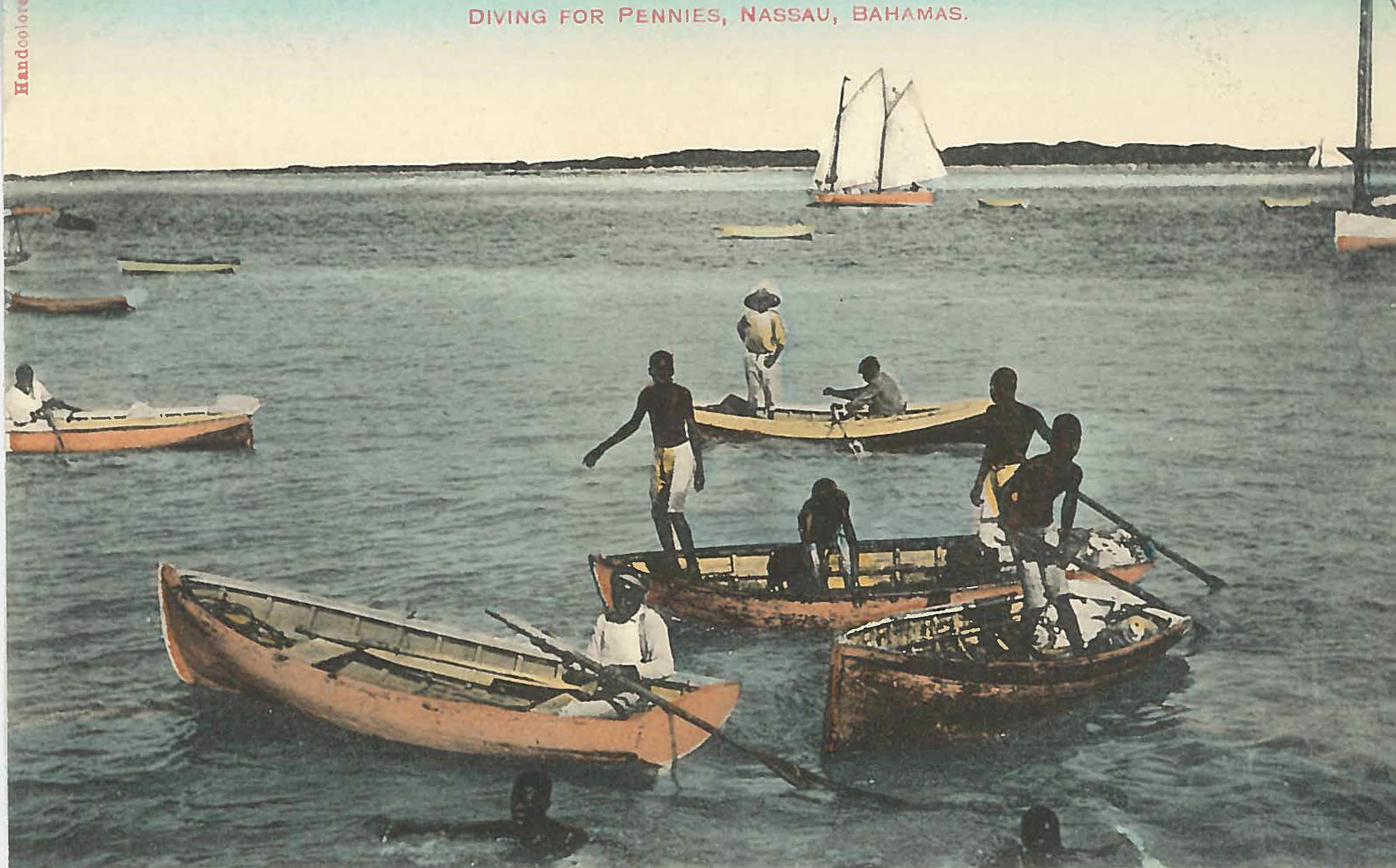

Diving for Pennies’ (estimated c.1870-1930), hand painted colonial era postcard. Photographer unknown. Images courtesy of the NAGB.

The ways in which art and especially photography captures this is significant because the gaze focuses in on an aspect that re-presents the entire culture or place while silencing everything else that was afoot then. So, exploitation, rape, and pillage were taken out of the text and what was seen was a happy native who smiled and was responsive to colonial projects.

The project to recreate nostalgic bliss in the hemisphere that was imperially controlled by the Europe plantation economy, and then by the US through the Monroe Doctrine without any mention of such devices, except to say how good those days were. This was instrumental in re-establishing a place of inequality and hierarchy where locals resided below, and international corporations resided above. The images left behind from those days, especially those black and white photos that render us happy with servitude are windows to how race and re-presentation become seriously troublesome by de-historicising and de-contextualising the image.

In hindsight, looking back on the new millennium seventeen years in, it no longer seems coincidental that at the same time the resort was taking off in the Caribbean those images of colonial subjectivity and bliss began to circulate in new and interesting ways. The resort was different in the way it ‘captured’ large swaths of land and gated them off from local communities. The image was also different because it was now us sending out those old images and offering ourselves as bait to entice fishers of men and women.

The old colonial office was now a tourism board, and the pith helmets were replaced by power suits or flowered shirts that sold us to them. We had gone from being rendered as darkies diving for pennies in Nassau harbour or ‘natives’ waiting for coppers in Grants Town, to a beautifully-landscaped and managed destination.

Tourism is not a problem! Tourism and culture when combined well can be an excellent driver of economic development and when locals and residents are involved as owners and entrepreneurs managers of their ownership. But when beaches are closed off to tourists, residents, and Bahamians who do not stay at a particular resort then it is damaging. It only becomes exploitative when sold as a foreign-owned enterprise that divests local development of any chance to focus on itself and creates absolute dependency. In fact, when it creates serious inequalities through disempowering both tourists and locals in favour of exploitative business practices is when everyone who visits and stays over suffers.

‘Colonial Basin and Harbour’ (estimated c.1870-1930), hand painted colonial era postcard. Photographer unknown. Images courtesy of the NAGB.

This is when resentments build and passions reignite. The images that begin to circulate allow this kind of festering resentment to build because rather than being depicted as equals, everyone who inhabits the space is re-presented as an exotic trope to a trolloping public, to use a term from the 19th century made famous by Anthony Trollop. Catherine Hall has worked with the ‘Going a –Trolloping: Imperial man travels the empire’ (1998) motif for a while, investigating the exploitative nature of this exploration and the ways in which masculinity was re-inscribed in different ways through the expansion of the empire.

The photographic image is a fabulous way to speak for and on behalf of a subject and to use the subject’s image to render the space open for business. It is also interesting that when the old images began to recirculate, they were never contextualized by present day images of progress and national development, but rather with mushrooming resorts and private playgrounds. Integration is missed.

The sale is of a romanticised old world existing in current day surroundings, much like the writer who claimed in the last three years that The Bahamas still did not come up to western standards of living. Rather we still inhabited cardboard huts and ramshackle, makeshift buildings that could be easily replaced when washed away. Perhaps Hurricane Matthew proved her wrong.

When projects like these create expectations of an Edenic paradise, they set the people up for failure. Culturally speaking, they render the entire culture subject to others, to cite Moira Ferguson’s title from her 1994 text. Bahamian culture and people are far more than a paradise that laments the missing past of slavery and the plantation; or where people are afraid to walk by graveyards, or wish for a return to the old ways when blacks knew their place and laws were obeyed without question.

These images are dangerously strong and resilient and re-present not a culture but the idea of a place where people can come and play. Art transcends a simple marketing tool that silences so much of what is here, the parts that travelers are truly interested in seeing but are closed off from them by gates that only allow particular images to filter through.

Why can’t tourism be used to drive Bahamian development that is beyond Paradise Island or Baha Mar? This place where the GDP is now outpaced by debt, where the level of inequality has soared at an alarming rate. If we examine the Gini coefficient, where the local or onshore economy has become a place that has dropped to the bottom of the ease of doing business list, and it takes months for regular business people to get permits, licenses, and approvals; where the investment status has been junked, and many of the regular people teeter precariously close to disaster and demise.

As much as we talk about tourism driving development, as it stands today, everything from legislation, to public policy stands against national development in the tourism sector. Bahamians are shut out by laws that allow transnational businesses to buy the best land between $1.00 and $10.00 an acre and then give the latter millions or trillions in ‘incentives.’

The image then that is being sold does not match the reality of the times and in fact, buries the local voice and the voices of anyone doing business in the country who does not come connected from above or sit at the top of the ivory tower.

Old images are fantastic, and the stories they tell can draw travelers and bolster a thriving tourism industry, but they can also re-create disparities and re-present old ideas that no longer serve anyone and undermine any form of national development other than transnational, no-boundary business that leaves no real wealth onshore.

Art is a fantastic tool for development, let’s use it wisely.