Are We One With Nature? G. Paul Dorfmuller’s Nassau Corner

By Letitia M. Pratt, The D’Aguilar Art Foundation

Recently, National Geographic published an article on their website acknowledging their racist coverage of colonised countries throughout the magazine’s history. Their current editor-in-chief, Susan Goldberg (the first woman and first Jewish person to claim that title) resolved to devote the April issue of the magazine to the topic of race, excavating the magazine’s problematic history and coming to terms with their role in reinforcing the racist ideals of the coloniser. Their photographers were, as stated by the article, “fascinated by the native person” in the colonised space, and often pictured the natives as “exotic” or “famously and frequently unclothed…noble savages.”[1] The Bahamas was not untouched by this viewpoint; historically, artists have captured our islands in various mediums in an effort to memorialise the ‘exotic’ beauty of the island natives. In these works, we are claimed to be as beautiful (or at least as interesting) as our environment. As our land. Our seas. We are noble savages, and savages are one with nature.

This viewpoint that is being explored in The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas’ current show, Transversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value. The exhibition includes work from visiting artists and expatriates who resolved to capture the sentimentality within the landscape and then-colonised Bahamian people. Within many of the works in the exhibition, the native is perceived to be as serene as the beach that stretches behind him, or as bustling as the trees that blows at his back. These renditions – however noble they are – caused the colonised subject to be objectified and to appear as foreign and untamed as the landscape that they inhibit, and within the white gaze the Black body becomes merely a prop indistinguishable from the natural environment.

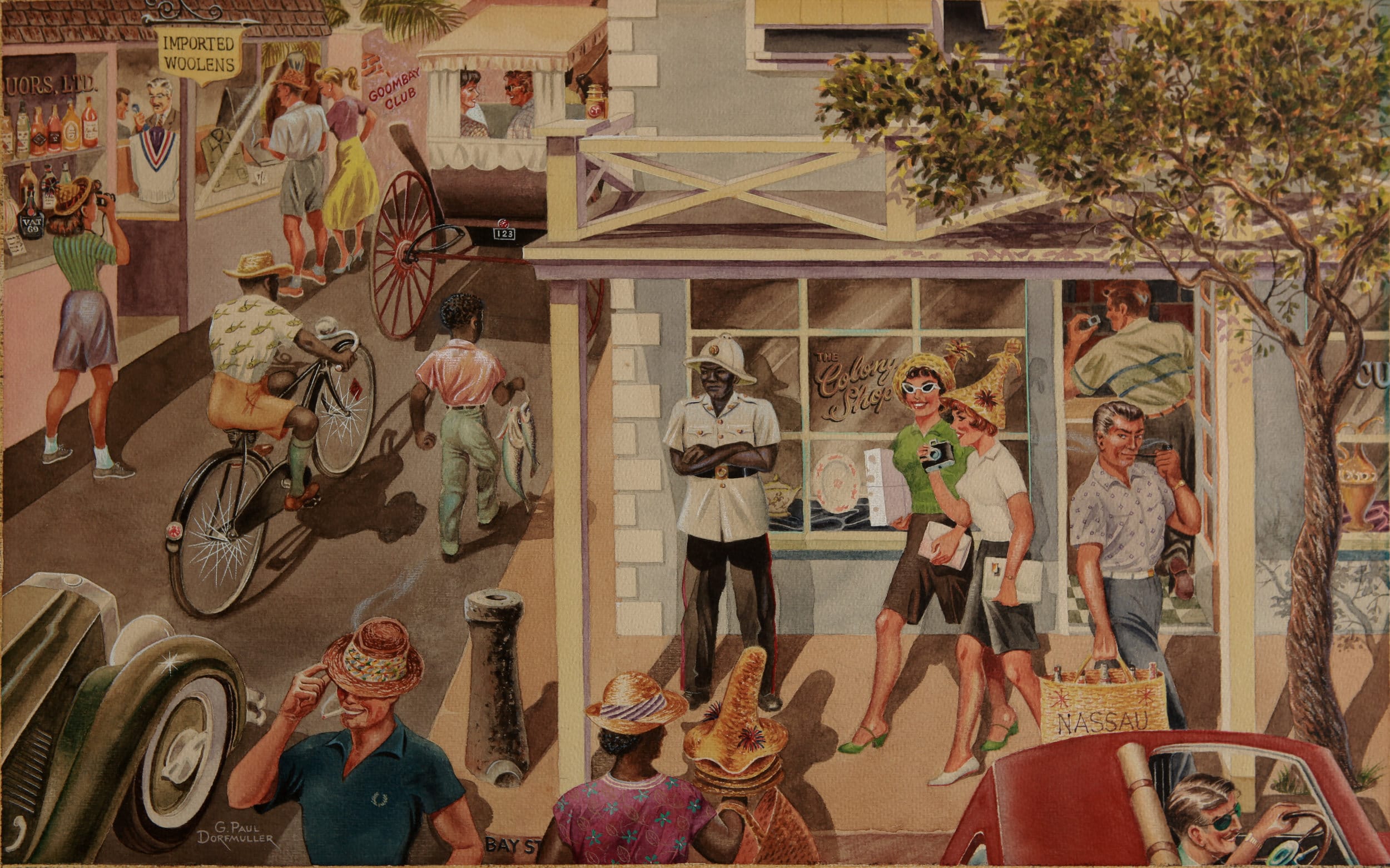

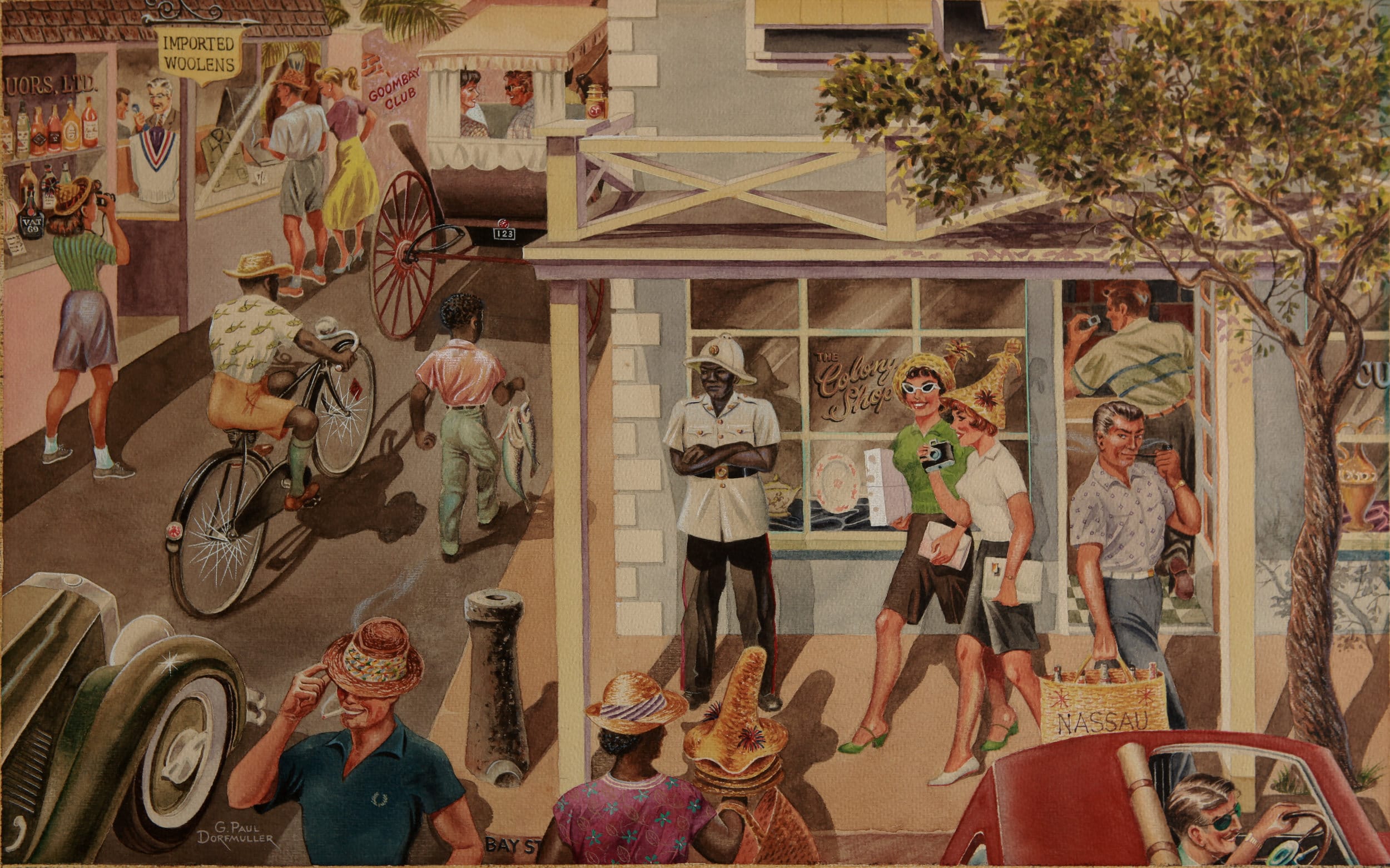

The most nefarious example of this type of this Black representation in art about The Bahamas are ones that tout the islands as a place ideal for travel and tourism. Modern renditions of this are the commercials (think…any commercial claiming it’s better in The Bahamas) that depict “natives” serving or entertaining the traveler. In all of these images, the Black body is a visual confirmation that the white subject has experienced the tropical not unlike the icon of bustling trees or the wide expanse of the open sea. A painting that exemplifies this best is G. Paul Dorfmuller’s Nassau Corner: currently a part of the exhibition, this painting captures this idiosyncrasy of the colonial gaze.

Dorfmuller’s rendition of a bustling street has very few organic indicators of the tropical: other than the single icon of the palm leaf on the upper left corner of the composition, the viewer sees a space filled with jubilant laughter of happy white tourists (symbolized by the cameras within many of their hands) in a place that could be anywhere. It is the Black people surrounding the tourists that solidifies the Caribbean-ness of this scene. Their figures are just as symbolically essential as the embroidered “Nassau” straw bag, or the “goombay club” sign; they are as natural and unmoving as the tree sticking out of a sidewalk. Their positions within the composition – three of them with their back to the viewer – dehumanises them, reinforcing their role as a prop of the environment, and immediately one gets the sense that this space is not for them.

Not much is known about G. Paul Dorfmuller. What is known is that he is American and that he practiced painting in the late 20th century, eventually visiting Nassau to complete this painting of the famous Bay Street scene. It can be approximated that this was between the late ‘50s through ‘60s because of the way the figures are dressed and the historic boom of the tourist industry at that time : this often attracted visiting artists like Dorfmuller who was interested in capturing the commercially picturesque scenes of Nassau tourism. This intention was not unlike the late 19th century photographers that resolved to promote scenic views of The Bahamas and tout it as a place worthy of the white traveler. It is a long-standing advertising ritual which asserts a few things: 1) it is better in The Bahamas, 2) our people, like our landscape, are exotic (and …interesting) and 3) this is a place of law. Of order. A child of the colony.

The colonial gaze longs to find order in a tropical space. In Nassau Corner, it is the people within the work that are ordered: the faceless black figures are delegated to symbols of the environment, while the affluent white visitors (indicated by their shopping activity) simply enjoy the space that seems to be intended for their consumption. At the heart of all this, placed in the center of the painting, there is the ultimate figure of colonial law: The Policeman.

The policeman is the only Black figure whose face we are allowed to see. His stern demeanor then becomes even more significant. Do the expressions of the other Black figures mirror his seriousness? Not at all likely – his symbolism sets him apart from the faceless natives, and his presence is meant to assure the viewer considering a vacation in The Bahamas that law will be kept. That the colonial order of things will be upheld. The Black figures will continue to be just that: figures – exotic people meant to entertain visitors and assure them that they are, indeed, in a tropical space.

No matter how noble it intended to be, Nassau Corner’s colonial view separates the visitors from the natives because of this dehumanisation. Perhaps Dorfmuller himself felt separate from the native people of the island and thought to capture this feeling. Perhaps he wanted to capture the disparity between native peoples and the affluent visitors. Whatever the case, this painting reinforces ideals of the colonial – represented by the centered, stern, icon of the policeman – by equating Bahamian people to the natural. By making them faceless trees sprouting out of concrete. By having them become one with nature.

“Trasversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value” will be on view at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas through July 29th, 2018.