By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett

The University of The Bahamas

It is the Visual Life of Social Affliction that speaks out against silence imposed over death. Undocumented death. If one lives an undocumented life, does one die an undocumented death?

Movie screening as part of the programming for “The Visual Life of Social Affliction”, a Small Axe Project.

The sea as life

One is buoyed on by levity, not dropped like a lead weight to the bottom of the sea, where there are souls that link from Africa to the New World and back again. These disembodied figures, souls linking lands, the submarine link, or submerged mother of Edward Brathwaite’s creation bind us together. They travel up from Haiti through the Ragged Island passage to northern shores. This is life suspended in a watery elixir of death and blue green beauty: the irony of nature.

The sea as death

Waves, swells, surges rush in flooding the plains, only these plains are the low-lying flat lands of island communities. Water washes with each wave, over, over, over roofs, houses, cars and people. The trauma of sea incursion onto the land will only be told by those who live. The silence of drowning is not silent.

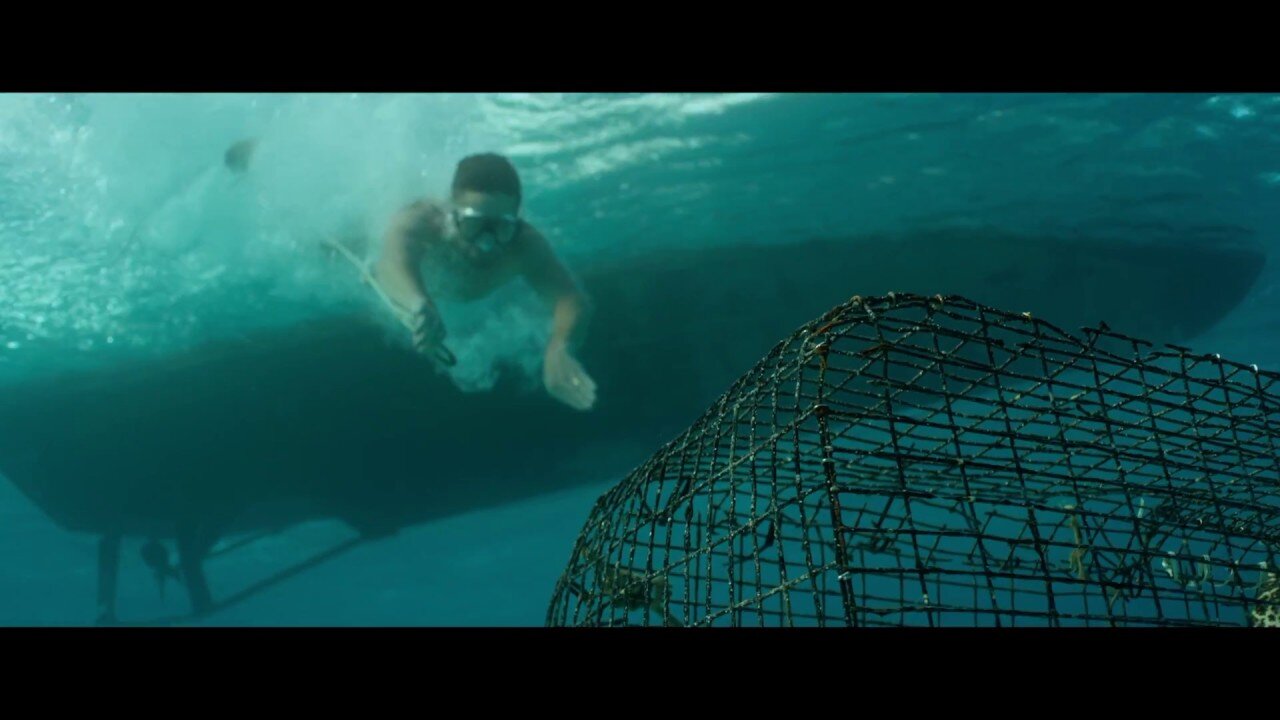

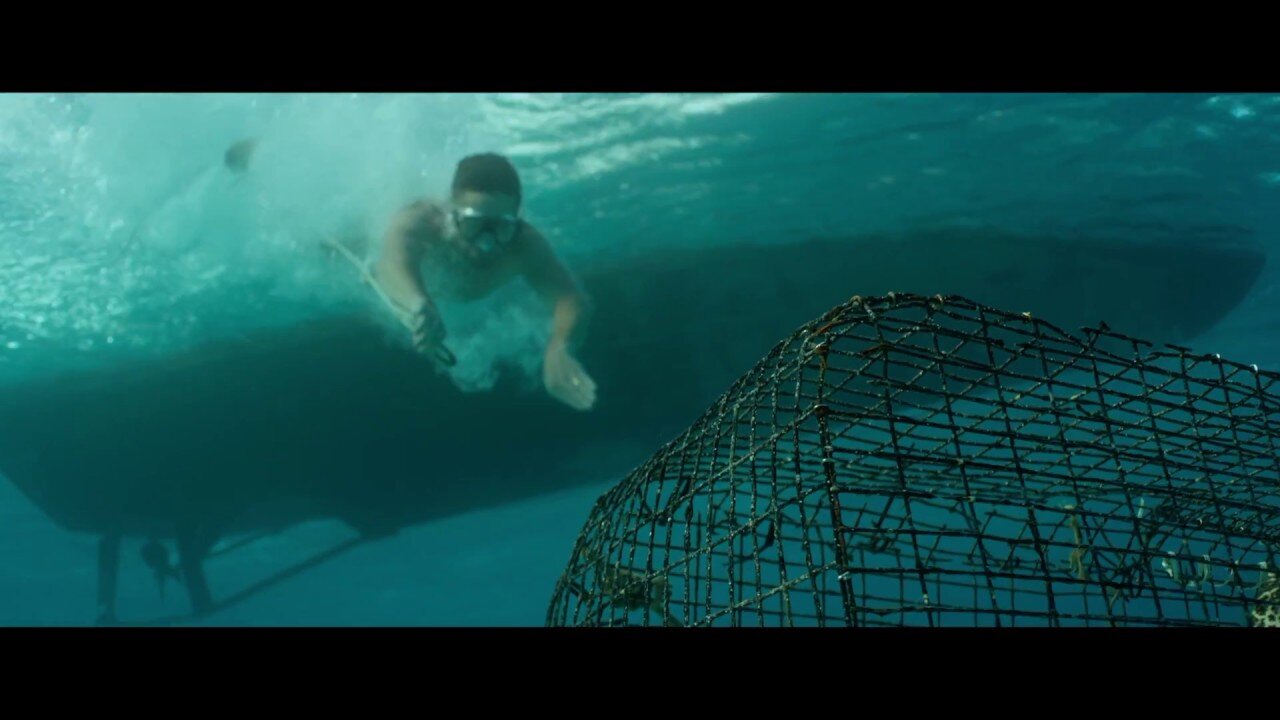

Film still from Kareem Mortimer’s “Cargo”.

The memories of enslaved Africans, piled into the bellies of boats to cross the Atlantic on the way to produce goods for European consumption. European products and industry of the finest quality (sugar, rum, molasses, coffee, and chocolate) built in and on the backs of those who were not thrown overboard, not left to die in a briny coffin, open to flow into the future, and return to the past, on a suspended sentence. The silence of slavery, not that bad, not that painful, easier here, not so long ago, far too long ago, unimportant, does not matter, of no consequence, all but devoured by epistemic foreclosure.

Death is an unsilencing of the silence of the living. It is the haunting of Diary of Souls (1999), as history repeats, in March 2019, Haitians drown in Bahamian waters, this time not buried on Bitter Guana Cay. This time it is more seen, more evident, more obvious because social media has changed life. It is like the Visual Life of Social Affliction (VLOSA) that speaks out against silence imposed over death. Undocumented death. If one lives an undocumented life, does one die an undocumented death? Is death, does death, does drowning document itself later, after the end of undocumented being? Perhaps it does. Kareem Mortimer’s award winning film Cargo (2017) challenges all these assumptions, unknowns, and asks even more questions. How do we rewrite this with a kinder ending?

Kareem Mortimer addresses the audience after the screening of his award winning film Cargo at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas.

The Visual Life of Social Affliction: A Small Axe Project, currently on display at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB), along with the NAGB, hosted the screening of Cargo on Thursday, October 23rd, 2019, at 8:00 p.m. The crowd was large and especially interested in how visual imagery gives new and different life to silenced realities, or disembodied figures shown on news reels that demonstrate, not humanity but influx, invasion, disease and contagion. Mortimer’s film revisions the lives of Haitians fleeing disaster and poverty in Haiti; and escaping exploitation, exile and migrancy in The Bahamas. These people can find themselves entombed in the bowels, belly, the innards of a boat that leaves them stranded in shallow or deep water. Left to disappear into the recesses of time, we see the lives they lived undocumented become visually documented and revalued. The semiology of this is significant. The significance of race as a floating signifier, according to Cultural Studies scholar Stuart Hall, is clearly palpable in this art form. Cinema, short experimental film and long narrative film bring another aspect of life to life as they tell stories through witness that are often lost in undocumentation. Mortimer works wonders with his casting, the storyline and lens show the pain, suffering, possibility, closure and too, corruption and inhumanity in two hours of image and sound. The sound of the boat engine, switching from two to one; and waves forgetfully breaking on a shore as death lays in the balance.

Cargo is a cinematic rendering of VLOSA; a recasting of Edwidge Danticat’s poignantly painful short story “Children of the Sea” (Krik? Krak! 1995). “They treat Haitians like dogs in The Bahamas, a woman says. To them, we are not human. Even though their music sounds like ours. Their people look like ours. Even though we had the same African fathers who probably crossed these same seas” (Danticat, 1995, p. 15) and so it goes, ebb and flow documenting the undocumented lives of undocumented migrants, documented refugees and work permit workers whose permits got washed away, taken away, burnt, lost in the storm.

The audience was captivated by the film Cargo.

Cargo gives us a moment to reimagine life and the possibility for humanity. We see undocumented lives lived and died in poverty yet deep humanity, though tragically flawed usually through no fault of their own. (Though the poor is usually blamed for their poverty). The un-hero protagonist, Kevin Pinder (played by Warren Brown), makes deeply flawed and misery-inducing, socially damning decisions/choices in his life. He ultimately creates destruction and discord in the lives of all those around him. His single-minded selfishness is reminiscent of Faustian greed/blindness. The Faustian deal is easy and smooth until the turning point when one of Pinder’s ‘victims’ returns to find him and remind him of his pact with the devil and to promise death upon him for abandoning vulnerable souls in the Berry Islands. They left behind and not rescued–as Pinder had promised they would be–the bad over takes the good at this point, though the turning point seems almost unremarkable, until it gathers speed and destroys just about every aspect of humanity.

Remarkably, the lesson Pinder gives to Celianne (Gessica Geneus) on how to float, a paradoxical moment in his less than stellar life, allows her to save her life and her son’s life. Yet what does this life saving, floating on the sea of death, hold for them as they come to the fore? Tragedy here is not undone, but speaks once more to documenting the undocumented life. Fiction is often less strange than life.

VLOSA brings a new vision as many of my students who attended, noted. The irony is that as often as these tragedies are (re)lived in The Bahamas, they are not remembered; human awareness of them vanishes shortly after they leave the headlines. This film captures stories in ways that allows us to see, hear, feel and experience so much of those undocumented migrants, refugees, immigrants and boat people washed up on inhospitable shores, branded through poor operation of law and exiled from opportunity through paperless existence.

This is the power of art. This is the power of creating dangerously, (Danticat, 2010)

It’s hard for those of us who are from places like Freetown or Port-au-Prince, and those of us who are immigrants who still have relatives living in places like Freetown or Port-au-Prince, not to wonder why the so-called developed world needs so desperately to distance itself from us, especially at times when an unimaginable disaster shows exactly how much alike we are.

The Visual Life of Social Affliction: A Small Axe Project and Mortimer’s Cargo bring to the fore the distance created between us and them, as Danticat discusses in “Another Country” of Hurricane Katrina. What of the voicing of undocumented lives adrift on seas of death that brings life through revalorisation voices from the diaspora under the sea, submarine links, submerged mother? We are here! Art is magic. Slavery is not that foreign. Death is not always the end.

Photo Captions:

Cargo-Screening-1: The audience was captivated by the film Cargo.

Cargo-Screening-3: Kareem Mortimer addresses the audience after the screening of his award winning film Cargo at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas.