Stories

The Visual Life Of Social Affliction: Structures of Violence in the Caribbean

Ian Bethell-Bennett · 13

There is a creole saying, “nou led, nou la” which translates to “we’re ugly, we’re here,” that is rich in culturally nuanced meaning and shows a serious persistence and insistence on showing up, being here, being present as has been evident in Haiti with the recent riots to protest the Petrocaribe corruption. Structural violence is rife and regionwide. At least we are here, even if we may be ugly.

In Bahamian artist Blue Curry’s The New Riviera (2014), we are not even here. This erasure of us from the scene is yet another form of unperceived structural violence, as we can also see in Curry’s Nassau From Above (2004). The deep silence of being silenced is ominous, and as we do as we are told, we are cradled into death, rocked into oblivion.

In this small place, people remain silenced by fear. The structures, invisible to the naked eye are clearly unveiled in the visual art of exposure. Visual image obscures what we see from day to day and shows us what often lies at the bottom of the swamp. As swaths of land sold to Disney, an Italian company, US company, UK company, Mexico company trading in Florida, Ocean Cay, Bimini, Rum Cay, Exuma, Eleuthera, the visual life of death becomes more apparent. Yet the structural violence of the disappearing young ‘troubled’ working-class men in police custody will never be challenged because we are afraid to starve, yet we are being devoured and fear not that.

Princess Margaret Hospital, a decoy to death, a beacon of rot and decay, a space of violence, interpersonal, apartheid system of health without official power to be so. It is the permission by government structures that allows the rot of violence to continue and the kind of violence that pervades each pore of the building and consumes as we enter that slowly and speedily kills, depending on one’s affliction. We are afflicted by the dearth of empathy, dearth of humanity, dearth of consideration. It kills! No insurance, no service. Bad service is as bad as no service. We live in the hyperloop between inhumanity and uncaring.

Space is one of those frontiers where people need it to live. The spatial erasure of lives and identities is a violence apparently so subtle that we would rather see an international corporation destroy us and devour our young, pillage our commons, than consider developing them ourselves.

Curry’s The New Riviera, a subtle nod at the structural violence that infiltrates Bahamian society, where a fabulous space is created, but locals might as well stay out unless you can pay to play and look a certain way. The whiteness imposed on space, erasing Blackness not through physical violence but through the stripping of identity and the creation of a subhuman group of servers is almost palpable. This is the visual life of affliction. It is the double consciousness that W. E. B du Bois describes in The Souls of Black Folks from 1903:

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Dr. Alia Al-Saji, associate professor of Philosophy at McGill has an interesting way of exploring this through the life of the visual image in her work on racialising Muslim women. It is similar to Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010) that unpicks the links between young, Black, working-class men and their eventual time in prison because the laws are stacked against them. In The Bahamas, a paradise for tourists to come and play, a reputed Black nation, because the majority are Black but the controlling minority remain white (Craton and Saunders, 2000; Saunders 2017; Saunders 1997). It remains, notwithstanding the claims that violently deny most working-class white Bahamians a space undeniably refuses space to these same young, Black men. The ironies abound as the violence of colonialist rhetoric and tools of oppression continue.

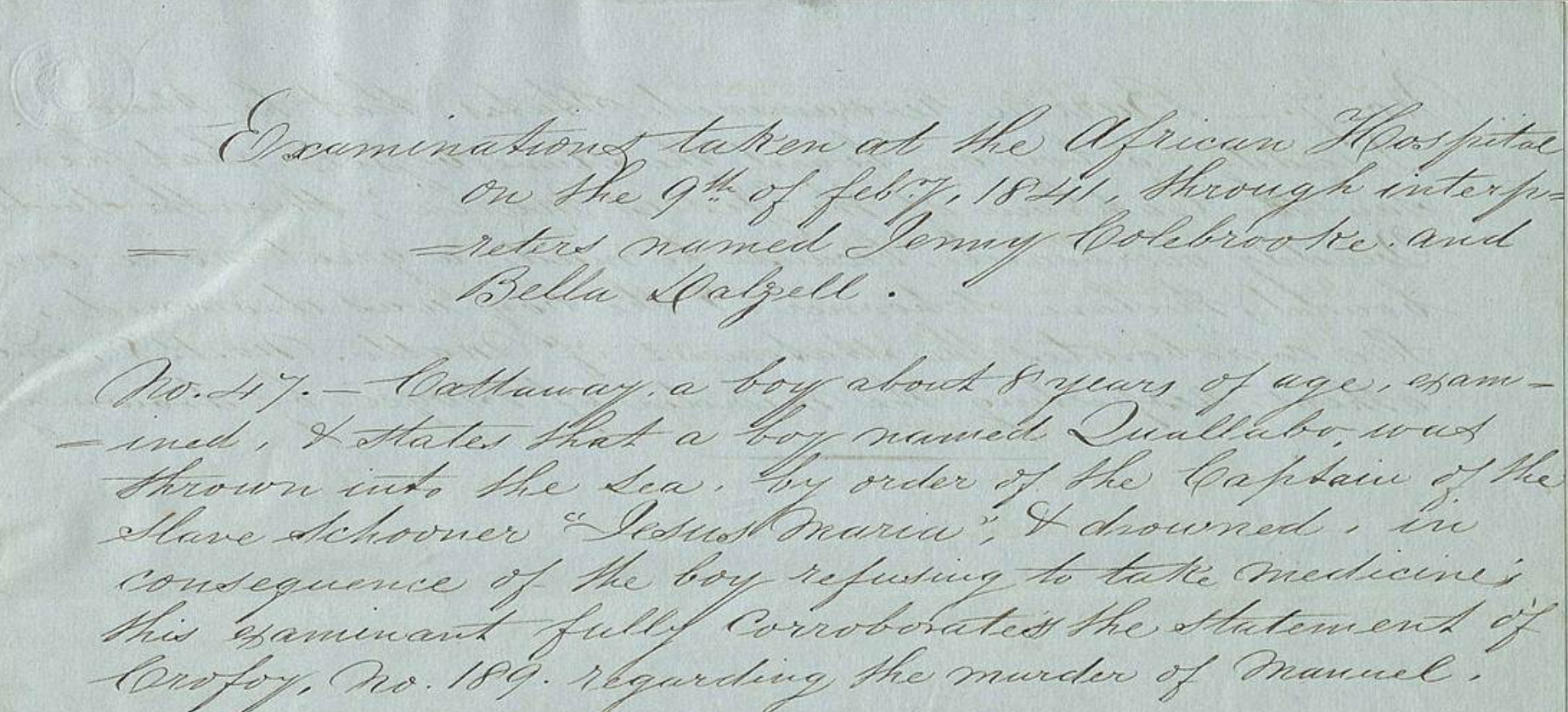

The African hospital no longer stands on Hospital Lane, but the public hospital need say nothing about the systemic apartheid even the Minister of Health recognizes, but somehow seems to do little about. This is the violence of structure. The structural violence that Johan Galtung works on in his Violence, Peace and Peace Research (1969) that occurs around the same time as Fanon’s work that explores both the naturalization and rationalization of race and then uses its power garnered through colonialism to blame its victims. Black Skin, White Masks (1952).

This discussion about young, Black men being the problem of the nation and young, Black women needing to keep their legs closed or being tied off after 3 children, has found a particular national resonance. However, the calling of other Blacks monkeys and dismissing them because of their homosexuality seems to speak to a rationalised self-hatred that is shared with others who are less empowered.

The challenge in this context is as Foucault points out with discursive structures that control and many visual artists from Dionne Benjamin-Smith and Nadine Seymour-Munroe to Blue Curry depict. They challenge Foucault’s discursive structures of power as employed by the government to argue against working on behalf of the people they represent. It is a structure that encourages violence against women, the expropriation of land and violence against youth to control the situation without ever understanding that, as Fanon argues, police and army officers are colonial agents who support the power asymmetry; they disempower, maim and kill the people they claim to protect.

As cruise ships dump waste, contaminate, pollute, and despoil land and sea, politicians’ denials of the same and lack of regulation to combat the real problems are stumbling blocks to success. These dynamics create the violence that threatens the national fabric because most young men from the underclass have nothing to lose, as Lavar Munroe’s work sometimes highlights yet the mechanisms of control, dogs, guns, laws, language all work to dehumanize, while the state says don’t question, just accept. The tragedy continues to unfold, yet we are numb to the pain.

Sadly, when we cannot see ourselves in our landscape it is hard to even have a double consciousness, a bifurcated self-identity. Discursive coloniality is rife and loaded with structural violence. We look forward to the Small Axe’s Project on The Visual Life Of Social Affliction, opening at the NAGB later this month. The Small Axe Project is an integrated publication undertaking devoted to Caribbean intellectual and artistic work, exercised over four platforms—Small Axe; sx salon, sx visualities, and sx archipelagos—each with a different structure, medium, and practice founded in 1997 and edited by Dr. David Scott.

Does the new riviera steer at us or through us? Are we made to see our likeness in these beautifully coiffed, plasticated models of a certain kind of style and beauty, distant from and often in contestation to Black beauty, or so the image tells us because, as Gilroy notes “there ain’t no black in the Union Jack” now replace riviera, paradise tropics and we see a new-old picture?

Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett is a Bahamian academic and creative whose work explores Caribbean migration, displacement, and identity through photography, poetry, and critical essays. Influenced by thinkers like Gloria Anzaldúa and Édouard Glissant, he examines colonial legacies, gentrification, and the privatisation of public resources.