by Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett.

During the United Nations Small Islands Developing States symposium held at the Meliá Cable Beach, we saw firsthand the importance of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), once referred to as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), but since the end of the first decade of the 21st-Century now called the SDGs. We also understand the need for our participation in disparate events and groups such as the World Fair, Expo 2020, Creative Nassau, Sustainable Nassau and Sustainable Exuma along with Bimini Blue, Save The Bays and other organizations that seek to move us out of the unsustainable downward spiral we are currently on. As has been noted by international and local experts, our culture is fragile, and we cannot survive and thrive, nor can we adapt without understanding where we are and where we would like to go from here. Cultural sustainability, then, relies on environmental sustainability and good policy to promote national longevity.

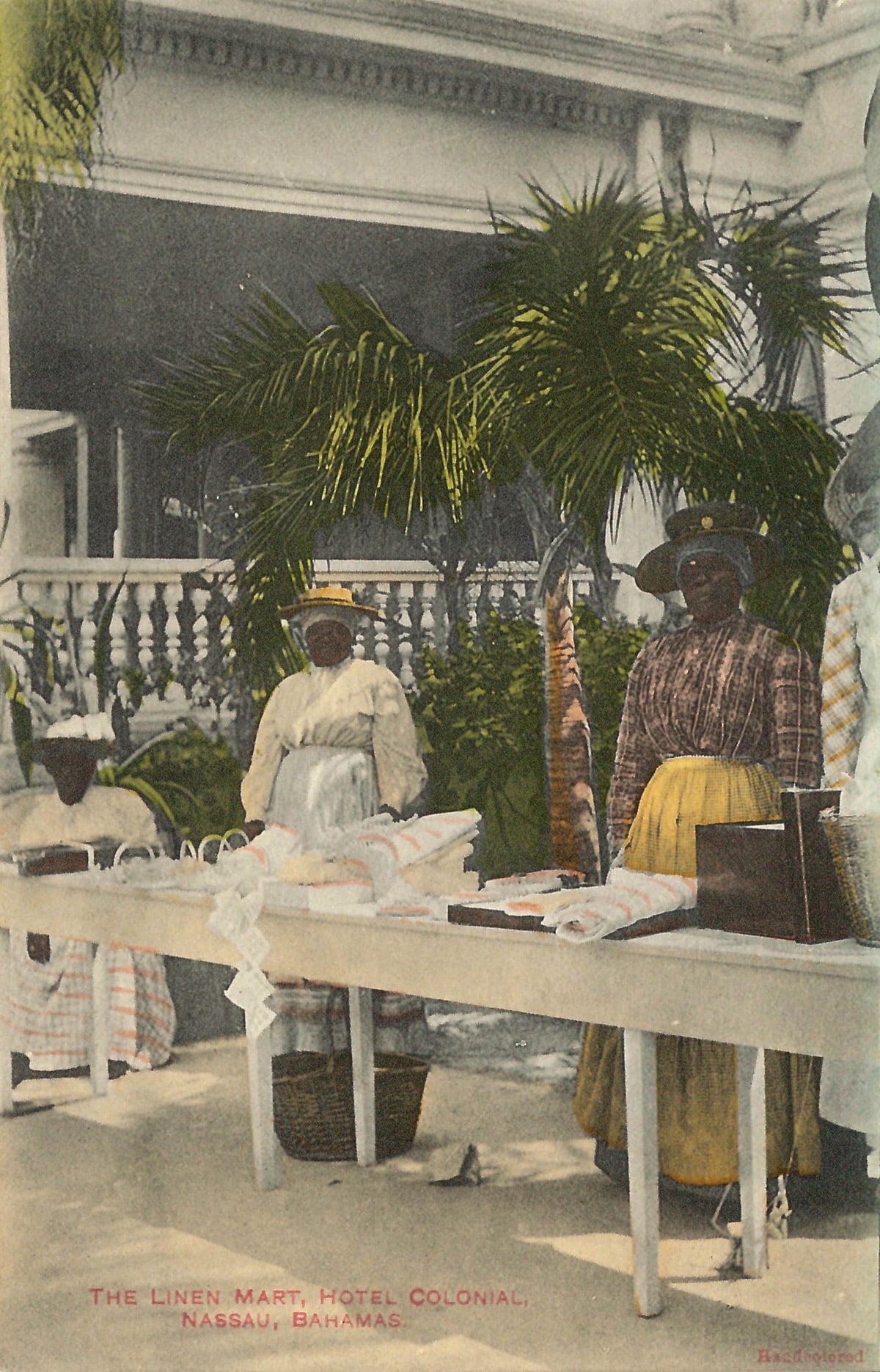

‘The Linen Mart at Hotel Colonial’ (estimated c.1890-1930). Handcoloured colonial-era postcard by unknown artist. Image courtesy of the NAGB. Part of the National Collection.

Meanwhile, in The Bahamas, we often talk about culture as if it were a sacred cow that is unrelated to anything we experience, do, say, eat, see or think. We express culture as if it had nothing to do with where we live, where we shop, where we dine, and how we do these things. On a recent trip to Barbados, an extremely expensive place for many folks, we visited the market because this is what the Bajans do; they shop at markets. While in Cuba markets are not as important as the dollar shops where Cubans were able to find inexpensive and hard to get products from outside. These were distinct from the local Cuban shops where limited supplies used to mean long queues. Of course, the music and the energy in these spaces were incredible. Half Way Tree, Kingston is as busy as it always has been for the last forty years, but the face has changed from the early 1980s when Jamaica was experiencing the blockade erected by the US against the Manley government to what it is now. These are all emblematic of growing and adapting cultures in the Caribbean.

Old Nassau, had that energy that is still evident in other city centres like Havana, Kingston, and Bridgetown before it was transformed into a near-derelict, void of local business space with extremely limited nightlife, though city centres like San Juan have changed with the globalising world and tastes. This global thrust causes troubles for many as it washes out the local colour unique to the place and creates a new entity that can be found almost anywhere. But even in these global centres, many small, robust local sections still exist. Globalisation has been good for those transnational brands, and not so good for small, local brands that have been devoured by the market.

Even Guinness is no longer Irish unless they bought it back. The Spanish used to boast about their ‘local’ beers and food. Since then, most of the Spanish beers have been globalised. However, Spain has a unique and distinct identity in every corner of the country. The Basques are a distinct people from the Catalans, and, as tourist or travelers, we respect that. In The Bahamas, however, we expect there to be one identity that molds all of the diverse people into one cookie-cutter frame of what we think of as Bahamian. Why can we accept the cultural diversity of Spain but not the cultural diversity of The Bahamas? Why does Nassau dictate the identity for all islands and islanders, settlements and towns? The richness and complexity of The Bahamas cannot and should not be compressed or condensed into a deeply deculturated, globalised, crime-ridden, dirty place for which international attraction is quickly waning.

Cultural diversity and historical influences

In discussion with a large group of young Bahamians, it was astonishing that most of the cultural history and the culture of the country was ignored, or, better put, ‘they didn’t know anything about it.’ Why was there a bat on Carmichael Road at the basketball park and bus stop? Was there a music recording studio in Nassau? When? It has become self-evident that we have done a poor job, as Nicolette Bethel and Patricia Glinton-Meicholas say, of appreciating our culture.

Pat Rahming, musician, poet, architect, cultural icon, is little known by many, though they may be able to recognise a song if it is played. When Compass Point Studios opened, they did a booming business. They brought stars and wealth to the island. Island Records had a large presence in the world of recording. The then proprietor created a brand that expanded to include the Compass Point hotel and restaurant. How do we forget these rich cultural moments so quickly? Why does a generation of young people not know that the Bat is there because Nassau was home to Bacardi for decades? How does one forget the transnational allure of The Bahamas to recording artists, musicians and visual artists, and international business and brands? Why do young people think so little of the culture and so of the country? Do we recall that Bob Marley, Grace Jones, among hundreds of others, would record here?

Do we recall that evenings were often spent telling stories and finding out who was whom? An old Bahamian way of life, finding out who ya people is, or who ya foolin wit and who dey people is, is quickly disappearing. As the young people say, ain’t nobody got time fa dat.

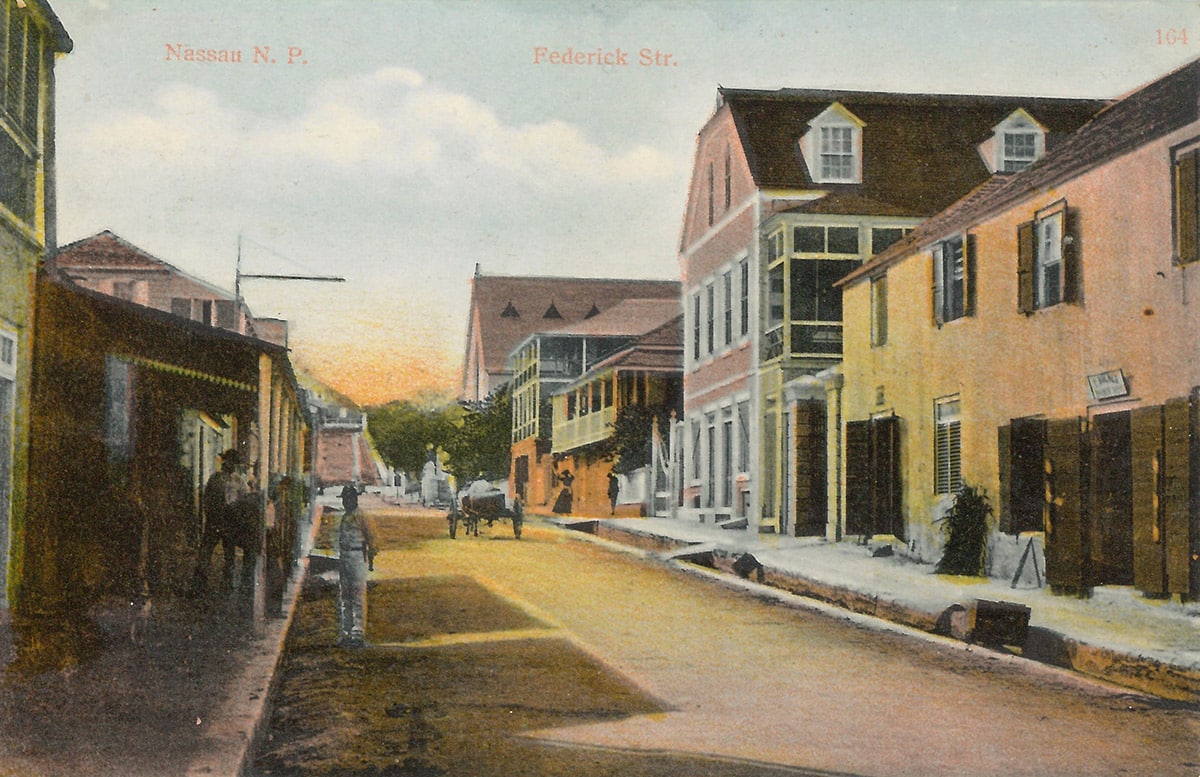

‘Federick Street’ (estimated c.1890-1930). Handcoloured colonial-era postcard by unknown artist. Image courtesy of the NAGB. Part of the National Collection.

So, what do we have time for? The music produced today is as rich and diverse as it used to be, but we never really talk about it. 102.9 FM, Island FM, and 92.5 FM Bahamian or Nuttin offer a diverse local programming that speaks to a changing cultural face. After the governmental shift in the 1992 general election opened the airwaves to voices like Island FM, there was more access to diversity than had been offered by the public-funded, government-controlled ZNS AM and FM. However, how far do any of these stations go in reaching the whole Bahamas? There was a time when this was the only way that people got news, through community announcements, for many non-readers or through the newspapers that arrived on mail boats days or weeks after their currency had expired. This has changed, and in fact, many islands have their papers now, but the need for information and connectivity reigns supreme.

But the way we envisage the country seems to be changing along an alarming trajectory. We do not see the need for small islands, cays, and even inhabited islands, according to some. The government should sell these off and move the people to elsewhere. What of the cultural diversity of the many faces of The Bahamas?

When, in 1967, the power shifted from the UBP to the PLP, a change in the local or Bahamian identity narrative also occurred. Nationalism took on some alarmingly exclusionary approaches to culture, considering who belonged and who did not; the who did not belong was more expansive than the who did. This project has produced a seriously skewed and distorted understanding of what Bahamian is; it has reduced it to a Nassau-centric understanding that excludes the importance and uniqueness of Fox Hill, Gambier, Adelaide and the significance of a name like Free Town.

Do young people understand the significance of Pat Rahming’s “Bain Town Woman,” Calypso Mama’s ‘Ask me why I Run’? Do we see the need to create lasting culture that is beyond an edifice to consumer-driven globalised product design? We do not discuss the living past that many old, hand-crafted postcards capture, though in the limited rendering of what was seen and none of what was happening behind the scenes.

We have distanced ourselves from the real dynamism of Bahamian living culture by creating façades to culture. We no longer offer the thriving cultural life that we can see in Havana or Kingston, the throb of life and the electricity of underground life, as well as the huge entertainment world caught on radar. The art scene is not just about pretty pictures and vibrant paintings; it is about the business of day-to-day life that is vanishing. Even the small Mom and Pop shop can no longer survive given the hard push of global capital, outward and inward migration. ‘Don’t Touch me tomato’ is as important to the Bahamian soundscape as is ‘Who let the dogs out,’ yet the music culture and clubs where locals gather is vanishing as we knew it, but we hope that a new generation can breathe new life into music.

Compass Point may be a shadow of its former self, but perhaps this will re-grow somewhere else in a different way. Perhaps the dynamism of the Over-The-Hill life will resurface elsewhere. Rather than simply referring to them as criminal ghetto dwellers, we will understand that the Yoruba Bantu, Igbo, Ashanti roots Cleveland Eneas wrote about in Bain Town may have been erased from current awareness. Perhaps the living will only be understood when other people who cannot go to Fox Hill or be shot down in gang violence, do as they do, will their frustration be understood and justified. Dr. Gail Saunders writes in ‘The Changing Face of Nassau’:

As Polly Pattullo (1996:7-12) also demonstrated, the development of tourism while raising the Standard of living for many in the region has also had a negative impact in some areas. The dependency on tourism and the change from elite tourism to mass tourism has had damaging effects on the economies, the socio-racial relations, the fragile infrastructure, cultural development, and the environment. (1997, p 21)

With that in mind, as well as bringing empty façades, great things are happening locally in culture. Filmmaking and its appreciation are taking off. The two local film festivals are testament to this. Island House (IHFF) and the Bahamas International Film Festival (BIFF) promote The Bahamas locally and internationally, and this brings Bahamian culture into sharp focus. Rum Fest and other large-scale socio-cultural events are attracting locals and international enthusiasts to our shores.

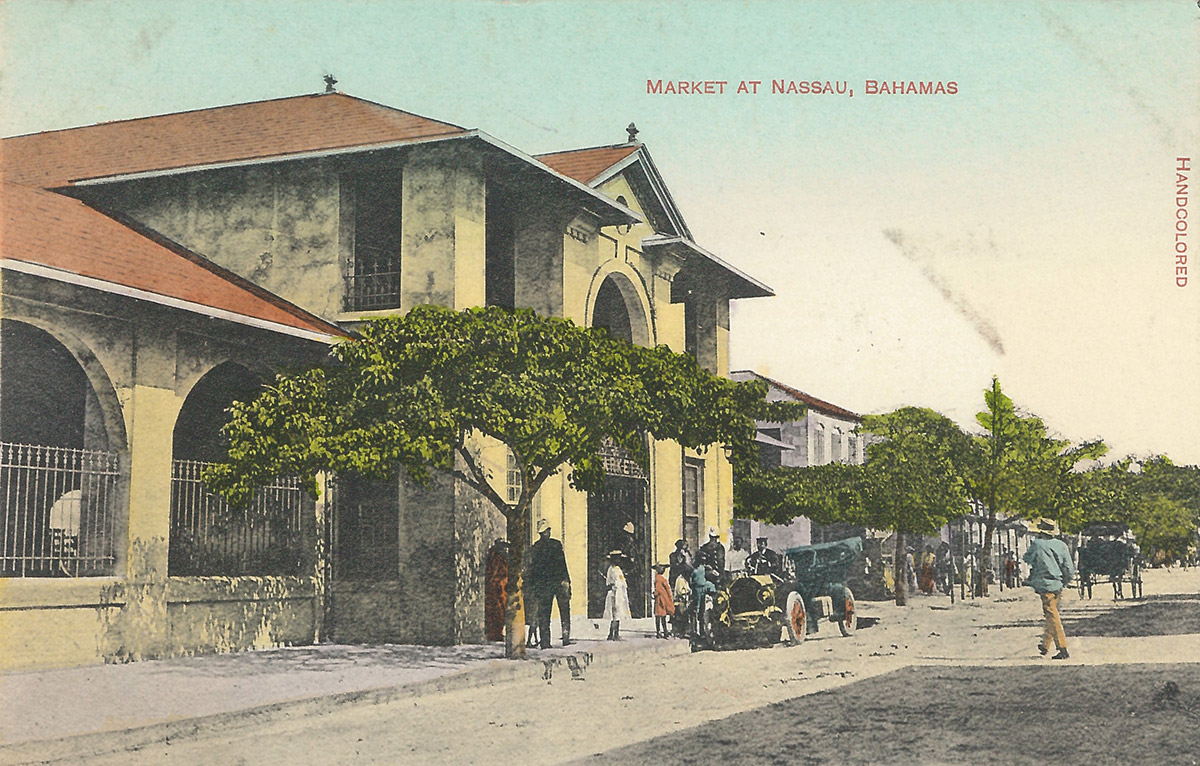

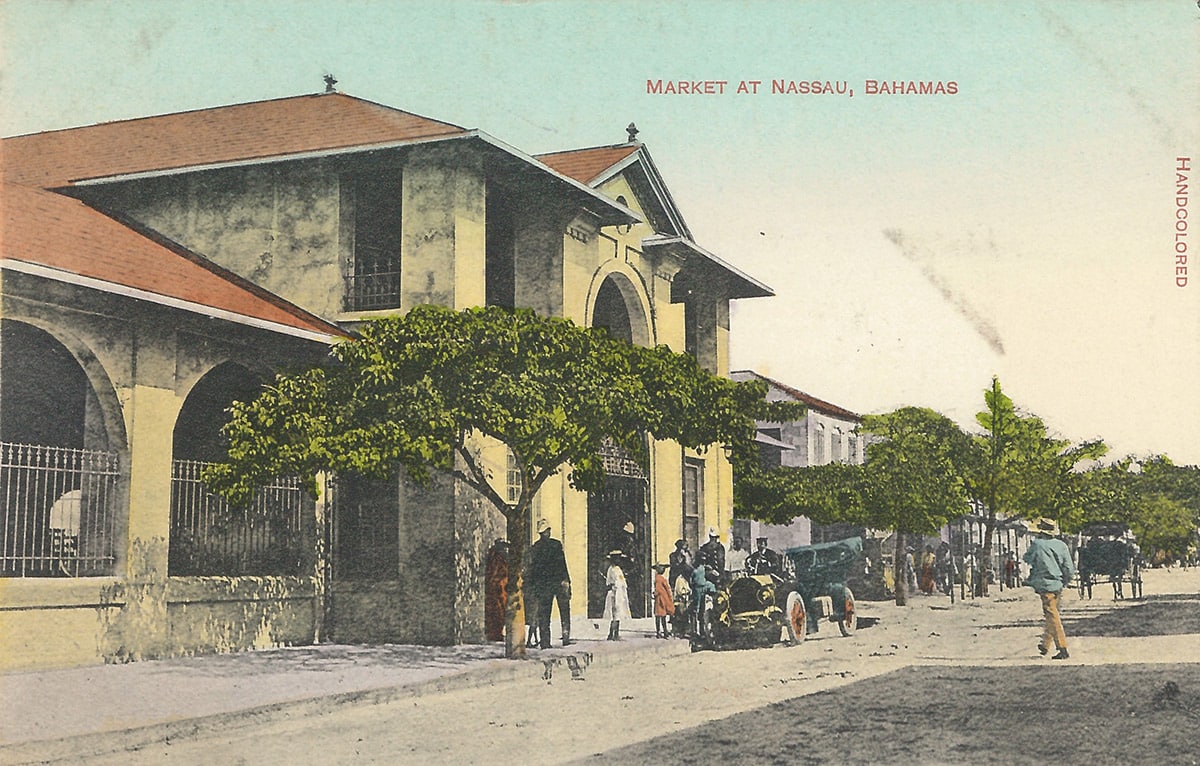

‘Market At Nassau, Bahamas’ (estimated c.1890-1930). Handcoloured colonial-era postcard by unknown artist. Image courtesy of the NAGB. Part of the National Collection.

Junkanoo Carnival is a rebranding of a carnival for local consumption with very little outside buy in because of the lack of lead time. If we take the culture of Bahia Carnival in Brazil, a community-led carnival that remains participatory, and Trinidad Carnival, where people begin to plan for next year as soon as this year’s event is over, then we know that we need to market years in advance.

Do we as a people own Rake ‘n’ Scrape? Do we own Bahamian bush medicine? Do we own our cities? Do we own our fishing and conching grounds? Do we even own our farms and other agricultural land? Do we participate fully in the creation, sustainability, and longevity of culture? When Expo 2020 offers models for future building, and the creative Nassau folks examine the need to ‘keep’ our culture alive, can Sustainable Nassau work to protect Nassau, Harbour Island’s Dunmore Town, Cupid’s Cay? Can these be protected as historical sites in line with the worth of UNESCO branding? What happens to them if they do get these designations? Can names like Bert Williams become a part of the story of successful Bahamians and a robust Bahamas? To be truly sustainable, we must answer yes to these questions.

The dynamism of Nassau and other cities and islands is being rebuilt and can be strengthened, but that includes Bahamians of all walks of life. It is not about one particular demographic or social group or even one ethnic group to the exclusion of all others. Nationalism has been important to the development of the country, but it has been so narrow in its optic and diction that it has created a false idea of Bahamianness that is too balkanised to speak for an entire archipelago that we boast about.

Do we still tell stories of young girls having to stay in from the fields when the ships were in port and the sailors out and about? Or has this memory to gone the way of the graveyards and local homes on other islands to provide second homes for Baby Boomers from elsewhere, as Nakeischea Loi Smith points out in her 2007 Masters Thesis, from MIT, that governments and policy makers have obviously ignored?