By Natalie Willis

“To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself.” – John Berger, “Ways of Seeing”.

The history of the nude, particularly of the female nude, in Western art history, treads a precarious line between the provocation of the mind and the body. This distinction between nakedness (as the state of being clothesless in life) and nudity (as the posed and framed view of a naked subject in an artwork) is key to the way we look at nudes. What makes a painting sensational and lewd, or a work of art to be considered as more than just erotica–is often left up to the opinions of those viewing it – more often than not, the opinions of those deemed “important” in the art world.

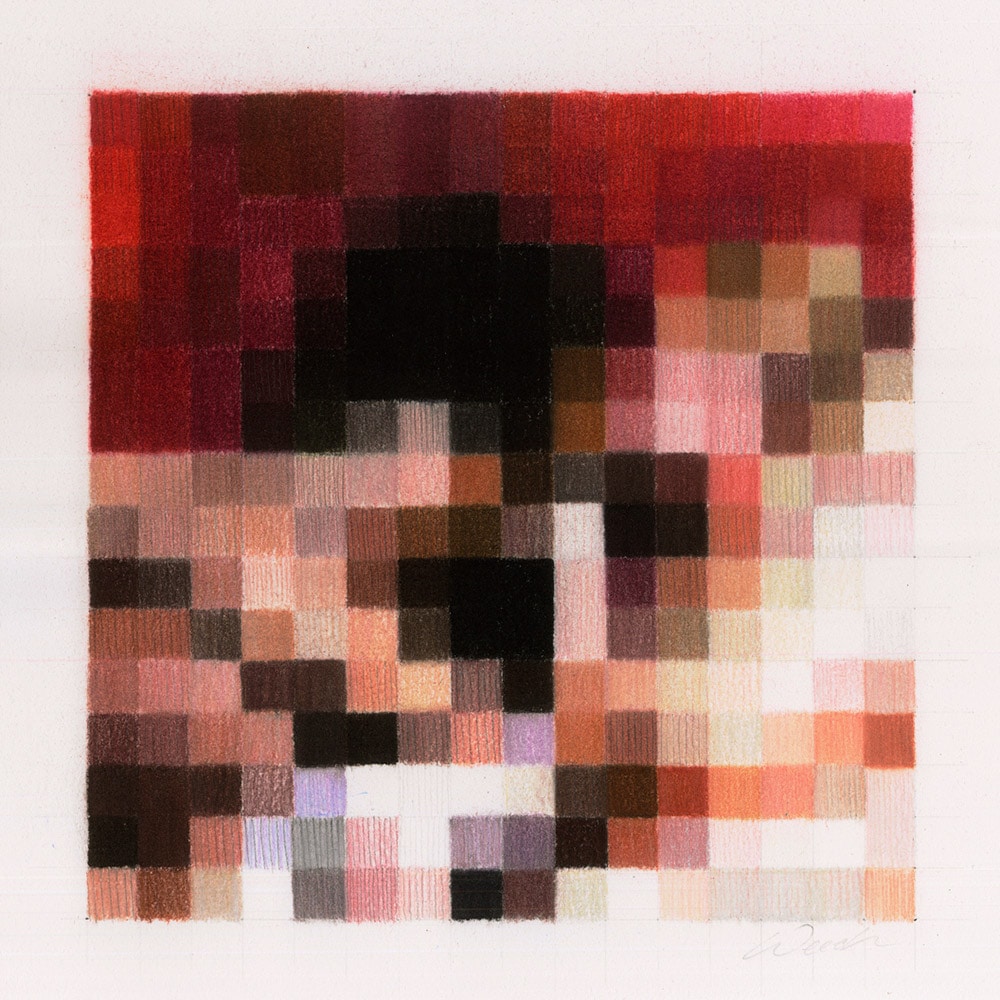

Drew Weech’s work on view in the NAGB’s new Permanent Exhibition “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean.”

Drew Weech follows along this centuries-old tradition- well, millennia if we are looking at art history in its fullness of the world and all its inclusivity – and he plays with it in an unabashedly cheeky manner, pun intended. Using traditional media to actualise the digital is an irreverent critique on the etiquette and boundaries of the history he references. In taking pornographic images of idealised women’s bodies, often surgically altered to realise these overly lauded and yet still arbitrary standards, Weech gives us a moment to think on the respectability politics of the naked feminine body and harkens to the origins of the Western nude. More often than not, the women painted were sex workers, as they were, of course, the only women at that time who would be willing to be paid to pose unclothed in “polite” society. Weech parallels this history into the digital era, taking women who fit into this role in contemporary society to render his image, all the while referencing the digital space they exist in.

In some ways, Weech is being critical of the male gaze as both artist and viewer and gives us a moment to consider the way women’s bodies are both sexualised and censored in public spaces, particularly within the museum. Nudity is common to world museums of art, but they are most often the bodies of white women and used to represent the ideal. By taking these white, idealised feminine forms and distorting them, deconstructing them down to hand-drawn pixels of colour, he is challenging the hierarchy of this ideal body. Displayed amongst the problematic imagery–in the NAGB’s new Permanent Exhibition “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean”–of the Black “mammy” of Khia Poitier’s “Alters/Altars” or Joann Behagg’s full-figured ceramic women, adorned in their head wraps – a device to “play down” the attractive and often exoticised appeal of historic Black hairstyles – Weech’s nudes serve as a sobering reminder of the way nudes are not just nudes, but bodies, and the way that Black bodies have been viewed over time. The white body of the porn star is an idealised one in regards to desire, higher up that hierarchy that designates ill-taste value on women, but it is also one that is marginalised as we see sex workers stigmatised and criminalised and denied fundamental rights for centuries. A history that Black women have known all too well, an uncomfortable similarity especially given the hyper-sexualisation of Black women from childhood experienced as a vestige of slavery today.

The questions that come up are centred around autonomy and the power of the gaze. The nude becomes a subject, no longer a person, and the discussion is more about their nudity than their person as it were. Subject hood replaces personhood and humanity, and the nude person becomes a topic of discussion, an idea, and their own lives rarely considered outside of whatever visual metaphors or contexts may be hanging around the image. Also, who does the looking and has the power in the looking? The matrix of men’s eyes versus women’s, Black and Brown versus white, are problematised in this work. It is a man doing the looking and rendering, as we have seen time after time again in art, but this man is Black, so some of his power is stripped. The women he renders have their power taken in a sense by way of being women, but they are white women. Who honestly has the power here, and how much does this depend on context and scenario? The sad truth of power hierarchies is that, aside from serving no one save but a select few, we all suffer in some ways, yet we must cling to what little we have.

Group II, 2018. Drew Weech. Pastel, pencil and graphite on paper. 12” x 12”. Works courtesy of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation

The power of looking or being the looked-at is a subtle, powerful, and insidious one. We are trained to look at certain bodies in specific ways, to strip away their humanity in our looking – porn stars, human zoos, ‘side-shows’ are all a part. Perhaps this is why pointing is so rude, a physical display of this power. However, perhaps point in that, and in all this, is that we need not only consider what power we do not have as people marginalised for race, gender, disability, and sexuality, but how many of us have privilege over another for where we are not marginalised. The simultaneous power and powerless is a way that we need to consider ourselves outside of that hierarchical binary to develop a deeper sense of empathy. We needn’t be one thing at a time, life is so often made of grey and pixelated pictures we can’t quite discern, we live in it even in this era of HD discrimination, but perhaps this duality is where we can find ways to mend the ways we have been hurt and prevent ourselves from hurting others. Just as Weech’s images come into more explicit focus upon their filtering through a phone camera or other device, sometimes it merely takes distance from what is in front of us to gain a better understanding for more level considerations.