By Natalie Willis

In this week’s interview we hear from Sonia Farmer on her contribution to “We Suffer To Remain”, an exhibition opening later this month that moves around ideas of slavery, time and memory, and how we begin to unpack and deal with these legacies. Farmer is a writer, visual artist, and small press publisher who uses letterpress printing, bookbinding, hand-papermaking, and digital projects to build narratives about the Caribbean space. She is the founder of Poinciana Paper Press, a small and independent press in Nassau which produces handmade and limited edition chapbooks of Caribbean literature and promotes the crafts of book arts through workshops and creative collaborations. The title for the exhibition comes from Farmer’s book produced for this show, “A True & Exact History”, which will be displayed alongside fellow Bahamian artists John Beadle and Anina Major works, as well as the work of Scottish artist Graham Fagen with his project from the 2015 Venice Biennale, “The Slave’s Lament”. Farmer moves us through not just the language written within the book itself, but around the art of bookmaking itself and how she crafts language to unpack the question of who we–as a country and as part of the Caribbean region–allowing to voice our histories.

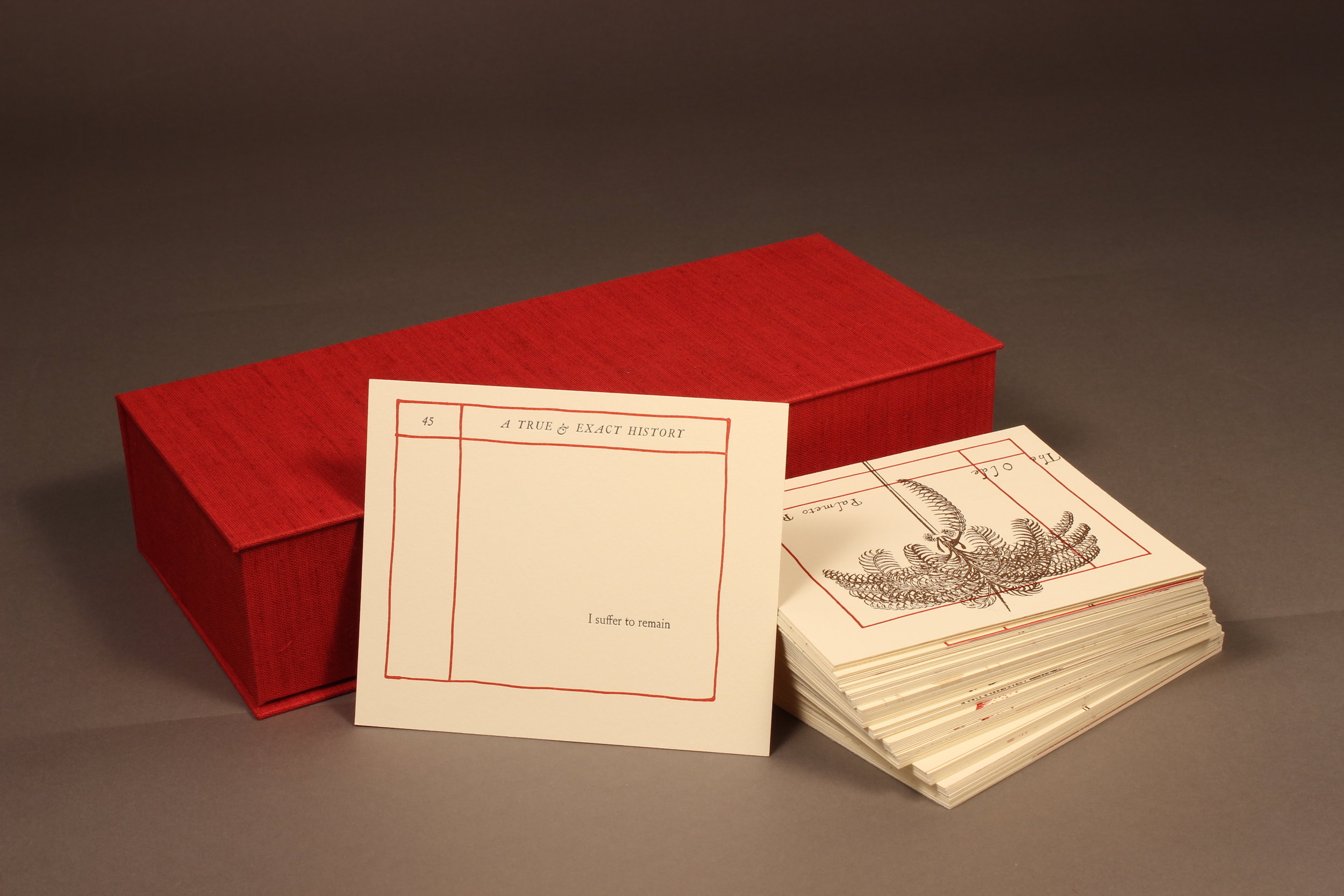

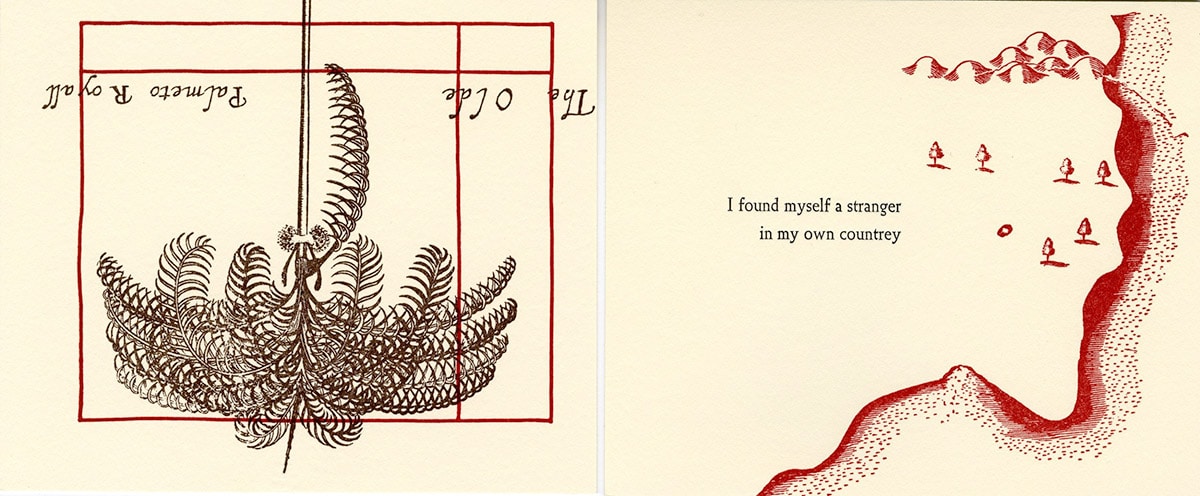

Letterpress print from “A True & Exact History” (2018) by Sonia Farmer.

Natalie Willis: Your work for “We Suffer To Remain” feels very much in keeping with what I know of your practice, but share with us a bit on how you think this particular work has built on your overall body of work. What does it add or what does it do that’s different?

Sonia Farmer: “A True & Exact History”, is the first, I would say, true ‘artist book’ I’ve ever made and it’s building upon my work as an artist making books, especially chapbooks. There are so many definitions for an artist book!

NW: Tell me a bit more about this as well then, because I admit that the world of book-arts is something I haven’t quite got a grip on and I think that I’m probably not the only one. It seems quite impenetrable or even secretive in its own way.

SF: For anyone who doesn’t know, a chapbook is usually a pamphlet with some folded folios, and it’s stitched in the middle. I usually use the form of the pamphlet to represent my writing because I love the array of possibilities that it can have, even though it’s such a simple structure. I also like its connection to small press culture which is something that I operate in as a book artist and that my press (Poinciana Paper Press) operates in.

A lot of my work to this point has been in the chapbook form, and not only the work that I make of my writing, but also the work I’ve published by other people. I love little ephemera pieces and full on chapbooks. I find artist books (and chapbooks do fall under artist books as a subcategory) to be works of art that utilise the form of the book, and you can see how chapbook clearly falls under that. I had never moved beyond the pamphlet-stitch for my work before this. Sure, I make a lot of blank journals and things like that with lots of multi-signature binding structures. But this is the first time I’ve made such a large, comprehensive book that required so much more consideration than what usually goes into a chapbook. So that’s how it builds upon my work so far in terms of the visual content.

NW: And how does it potentially build on your writing practice, if we’re speaking of the two separately?

SF: Regarding my writing practice, this doesn’t feel like it necessarily builds on my body of writing. I’m not taking things to the next stage per se, it’s just a continuation of my preferred writing practice which involves erasure or found text, or some sort of textual interruption or a manipulation of existing narrative in order to create a new narrative. That’s what I enjoy most. In my previous work I’ve done erasures of canonical books such as “Wide Sargasso Sea” and “Jane Eyre”. If I write my narrative poems, even that is usually in conversation with an existing narrative. For example, when I confront the myth of the Gaulin in “This Is Not A Fairytale” or my work in “Infidelities” where I’m trying to disrupt the myth of Anne Bonney.

This particular book is an erasure of Richard Ligon’s “A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes” (1657). For the sake of definition, erasure is a process by which one uses an existing text to recreate new bodies of text by removing text and leaving other text exposed. So I’m using the language of an existing narrative to create a new narrative, which is what I love doing most in my work, and this particular erasure is my most restrictive ever. By that I mean I’m using only the text I see, exactly in the order that I see it. Sometimes I take a lot of liberties when I use found text or erasure, I move and shift things around all the time. But for this one, the restriction is that I have to use what’s in front of me in chronological order. So in that sense this is probably the first true erasure I’ve ever done, maybe even the only one – who knows!?

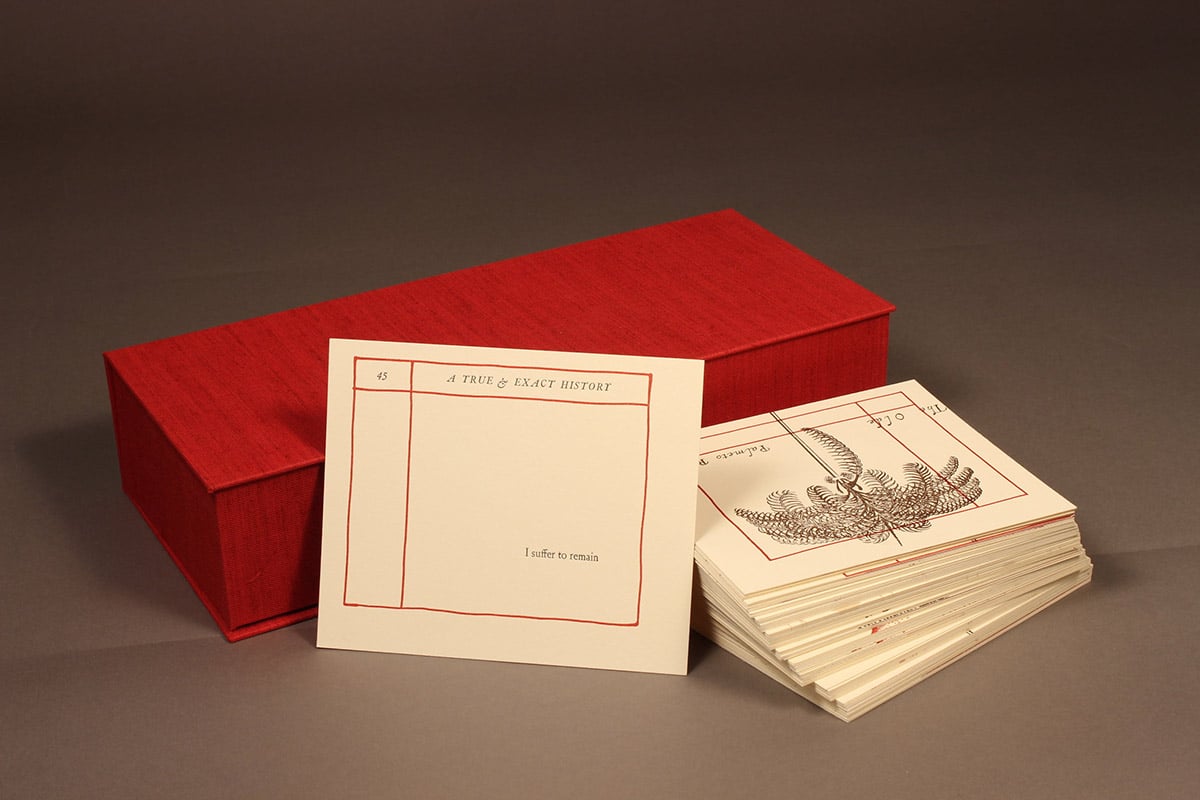

“A True & Exact History” (2018), Sonia Farmer, letterpress printed book, Erasure of Richard Ligon’s “A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes” (1657), letterpress-printed and collected into a handmade clamshell box measured, 5.5″ x 13″ (closed box). Edition of 25. Image courtesy of Sonia Farmer.

NW: For you, how much of the work becomes storytelling, and how to what extent is it potentially trying to give shape to ill-written or ambiguous or missing history? Given the region we come from and that the ideas around “We Suffer To Remain” come from, history and oral tradition are both important but sometimes conflicting ideas.

SF: Both of these ideas are in the work for sure. There’s a degree of storytelling, and I think for me the storytelling comes first, and through that I am then addressing history in the Caribbean space. That almost becomes a by-product of the storytelling for me. When I began writing for this project, and truly when I write anything, I feel like anyone else who makes art. By art, I mean anything: it can be music, writing, any of their artmaking forms. When we start off making, to be honest with ourselves we don’t truly know what we’re doing. It’s a bit of a subconscious act. You do go into this different space when you’re creating, and then eventually as you make the piece, or even after and you go in and edit it, you start to see what you were doing. Maybe you tweak the piece then, to do a little bit more of what it seems like it is you’re wanting or trying to do.

NW: So the work leads you in its own way?

SF: Yes, so when I encountered Richard Ligon’s book through Annalee Davis at the Fresh Milk Art Platform–pulled from the Colleen Lewis Reading Room at Fresh Milk–and I was just drawn to this book that I had heard mentioned before but never quite explored. I had this desire to play with his language because, I mean, Ligon is a charming narrator. It was a pleasure to work with his written voice and engage with what he was doing all those years ago. He might not necessarily be writing exactly what we thinks he’s writing, or even what we think he should write. The book that Annalee gave me was an edited version and it was divided into 5 sections – which is not true of the original manuscript, but I approached each section one in turn.

When I’m doing erasures I can’t say that I have a plan, I do definitely let the language lead the discussion or lead the narrative. I just started picking out things that were standing out to me, creating this narrative that I wasn’t sure would have an end, or where the end could be. Through that I started realising I was picking up on the same things as time went on, I found myself saying the same things in different ways, and thinking about creating a new narrative that subverts Ligon’s voice of authority about the Caribbean space. I was trying to think about bringing out other voices. There’s no singular voice in the narrative I’ve created, there are many voices – none of which I think are Ligon’s, actually. I think they more belong to the people of the island, or islands, if we think of the Caribbean as a homogenous space as so many people do.

There’s never any specificity in the narrative, and there’s a reason for that, because I am interrogating the homogenous space of the Caribbean so sometimes the voices are maybe voices of people, of an omniscient narrator, maybe it’s the island itself. So through the act of writing, in that way I think that I am, when I finished writing I realised what I was doing was interrogating the authority of these historical accounts written by other people, by colonisers, and trying to not necessarily replace them because their narratives are so entrenched in our society, but to try to add another possibility or path or voice to the equation.

Next week we will continue the conversation with Farmer, delving more deeply into ideas of the quality of time in her work, how time works in the Caribbean, and what it means for her to be an artist working with language in this space. “We Suffer To Remain” opens on Thursday, March 22nd, 2018 at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, and the opening will be free and open to the wider public.