By Natascha Vazquez.

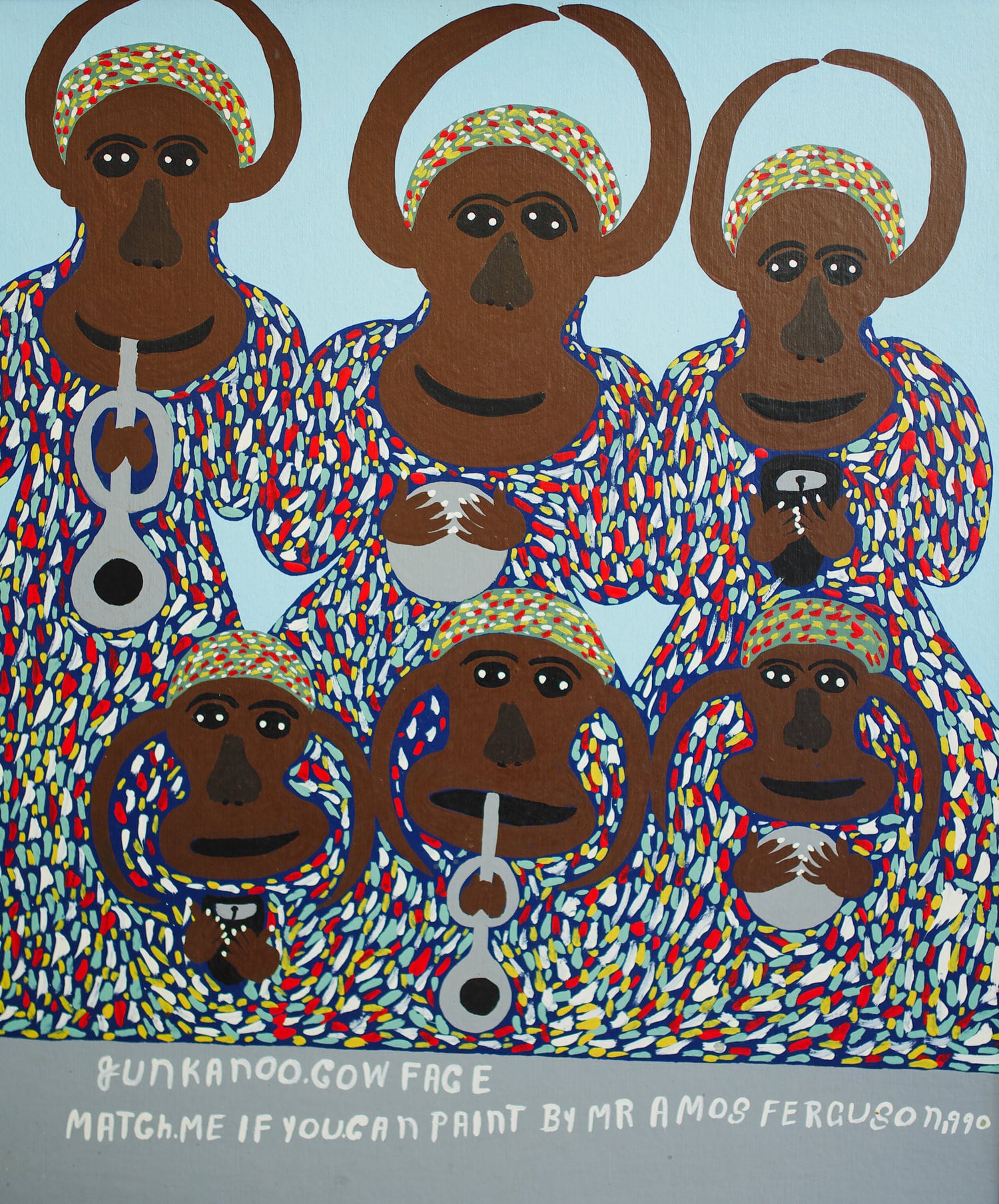

Bahamian artist and icon, Amos Ferguson radiantly portrays the spirit of Junkanoo through an energetic array of repeated imagery and texture in Junkanoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can, an iconic piece in the Gallery’s National Collection. His interest in flattening the picture plane and depicting a graphic quality to the work is evident in this work, nodding to the style that he became widely known for. Ferguson used colour and repetition of form for impact and clarity. Arrangements of patterns flood his paintings, a visual language closely related to that of Bahamian culture, and in particular Junkanoo.

Amos Ferguson was born in a small village in The Exumas, Bahamas on February 28th 1920. He grew up on a farm as his parents were sharecroppers – humbly living amongst his six siblings with no electricity. His family primarily grew sugar cane, beans and corn, selling the crops at the local market. Ferguson’s father was also a preacher and the pastor of Palestine Union Baptist Church. He was very close with his father, and spent a lot of time reading the bible and praying. He gained a deep appreciation and understanding of God through his relationship with his father, and grew into a deeply religious man. According to Ferguson, “See, I stick with my daddy. He was a religious man, and I stick with him. All he into, the bible. Speak good ‘tings, tell you good from bad.” Many of Ferguson’s paintings were heavily influenced by his religious background.

Bloneva King, also known as Bea, worked nearby Ferguson in the Nassau straw market for many years selling traditional woven baskets and hats. Ferguson and her collaborated in their craft – her baskets with his painted pictures set her trade apart from the other venues in the market. Bea became Ferguson’s wife and artistic mentor, supporting his talents and later assisting him with the marketing of his work. It is said that his folk and intuitive art style grew from the time spent at the straw market, influenced by decorative and craft works that he encountered.

Folk art encompasses art produced from laboring tradespeople or by peasants. It is said to be primarily utilitarian and decorative rather than purely aesthetic. Perhaps the early works of Ferguson within the straw market context fit under the folk genre, but pulled away from that as his artistic career developed into a deeper intuitive art practice. However, the aesthetic of folk art continued to weave itself within his work. Many of Ferguson’s paintings include hand-painted text with the famous words “Paint by Mr. Amos Ferguson” – shining a light on his decorative and natural approach to painting. The writing sitting directly on the work changes its formality, giving a large variety of audiences insight into the work and into his thinking.

Throughout Ferguson’s life, he also worked as an upholsterer, furniture finisher, and house painter. Evidence of his carpentry background are manifested in his paintings, primarily using house paints and found materials as his central medium. He achieved many of his dynamic pattern work with the tops and ends of nails dipped into paint. Ferguson also used house boards as a surface for many of his paintings.

Junkanoo was a central recurring theme in many of his works. Junkanoo is a Bahamian national festival consisting of a medley of colours and sounds. The vivacious sounds of goat skin drums, whistles, brass instruments and cowbells flood Bay Street in New Providence and other Family Islands during the early morning hours on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day. Brilliantly coloured costumes are tediously constructed in shacks throughout the year to be worn during the festival. They come alive through the rhythmic movement of dancers wearing them, intensively animating the brightly colored designs.

Traditionally, Junkanoo costumes were made with discarded or recycled items – rags, newspaper, sponges – and later developed in the 60s to crepe paper and cardboard. Today, Junkanoo costumes are constructed with a magnitude of craft material ranging from rhinestones to feathers to glitter. For that reason, viewers may not immediately draw a connection between Ferguson’s work and the festival. The animal faces evident in many of his Junkanoo themed paintings are reminiscent of Junkanoo’s original roots as a West African ritual in which people wore masks with large tusks on their heads and stood on stilts. Often times, real cow’s horns were attached to the headdress and tied under the chin, along with a black jacket and a tail called Reel-A-Tail, made out of empty bobbin spools.

Ferguson’s repetition of imagery, colour and texture in ‘Junkanoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can’ captures the spirit of Junkanoo – the rapid beats, the rhythmic dancing of the rush out, and the sea of craft that lights up the dark, early morning sky.

Six cow-faced humans occupy the composition of this painting, three lined horizontally at the top standing tall and three beneath, parallel to the top crouching down. The first figure appears to be holding a trumpet, although it is hard to distinguish at first look because of Ferguson’s preservation of flatness. He uses no sense of perspective, further flattening out the picture plane and adding to the brilliant abstract quality that his paintings obtain. The figure is a brown tone, contrasting beautifully with his highly colored and patterned attire, which appears to be a robe of some sort. Through tediously spotted marks of different colours, Ferguson achieves a sense of texture that is also repeated on the figure’s headdress. Two pointed horns begin at the head and bend around as they ascend, mimicking that of a real cow. The figure is gently smirking, revealing a light-hearted and celebratory expression.

The following five figures are dressed the same with similar expressions – the only change with each is the instrument in which they hold. The second is tenderly holding a drum, the third a cow bell, the fourth another cow bell, the fifth a trumpet and the last one a drum. The repetition of form, colour and imagery in this painting effectively mimics the repetitive nature of a Junkanoo procession and the beat of a rush out and even as far as a pattern engrained in a costume. The visual recurrence in this work imitates the nature of Junkanoo, without the imagery needing to be there at all.

Ferguson’s iconic polka-dotted textures are similar to those of contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama, known as the “Polka-Dot Princess”, who is interested in psychedelic colors, repetition and pattern. Kusama creates installations, paintings and collages all revolving around the repetition of vibrantly coloured circles. Similar to another Bahamian iconic artist, Kendal Hanna, Kusama’s interest for polka-dots revolves around her suffering from a mental disorder that consists of intense audio-visual hallucinations.

These are just a few examples of the overlapping between artist, their life, and their art. Hanna’s schizophrenia and his ability to freely experiment with abstraction, Kusama’s hallucinations and obsession for polka-dots, and Ferguson’s love for the Bahamian culture. No matter how radically different, each artist correspondingly weaves his or her life experiences within their art practice.