A Body Of My Own: Anina Major reclaims the body

By Letitia M. Pratt

In the past few months, there have been four reported incidents of sexual assault in Nassau: three minors abducted on their street while walking home, and one adult, forced to drive to the site of her abuse. This woman, these girls are the victims of the poisonous vestiges of unchecked toxic masculinity – the type of masculinity that thrives on the ownership of the feminine body and flourishes when it has captured full control. Thus, a significant element of the shared feminine experience is the fear of losing our bodies to this abuse. This fear forces us to resist, to rebel, and to ostentatiously claim our bodies as our own. It is not unusual for women artists to practice this rebellion through their work and Anina Major’s piece within the British Council supported exhibition, We Suffer to Remain, encapsulates this perfectly. Centering around the black woman’s body, To Have and Not to Own (2018), and the very ritual of its creation, grew from the process of reclamation.

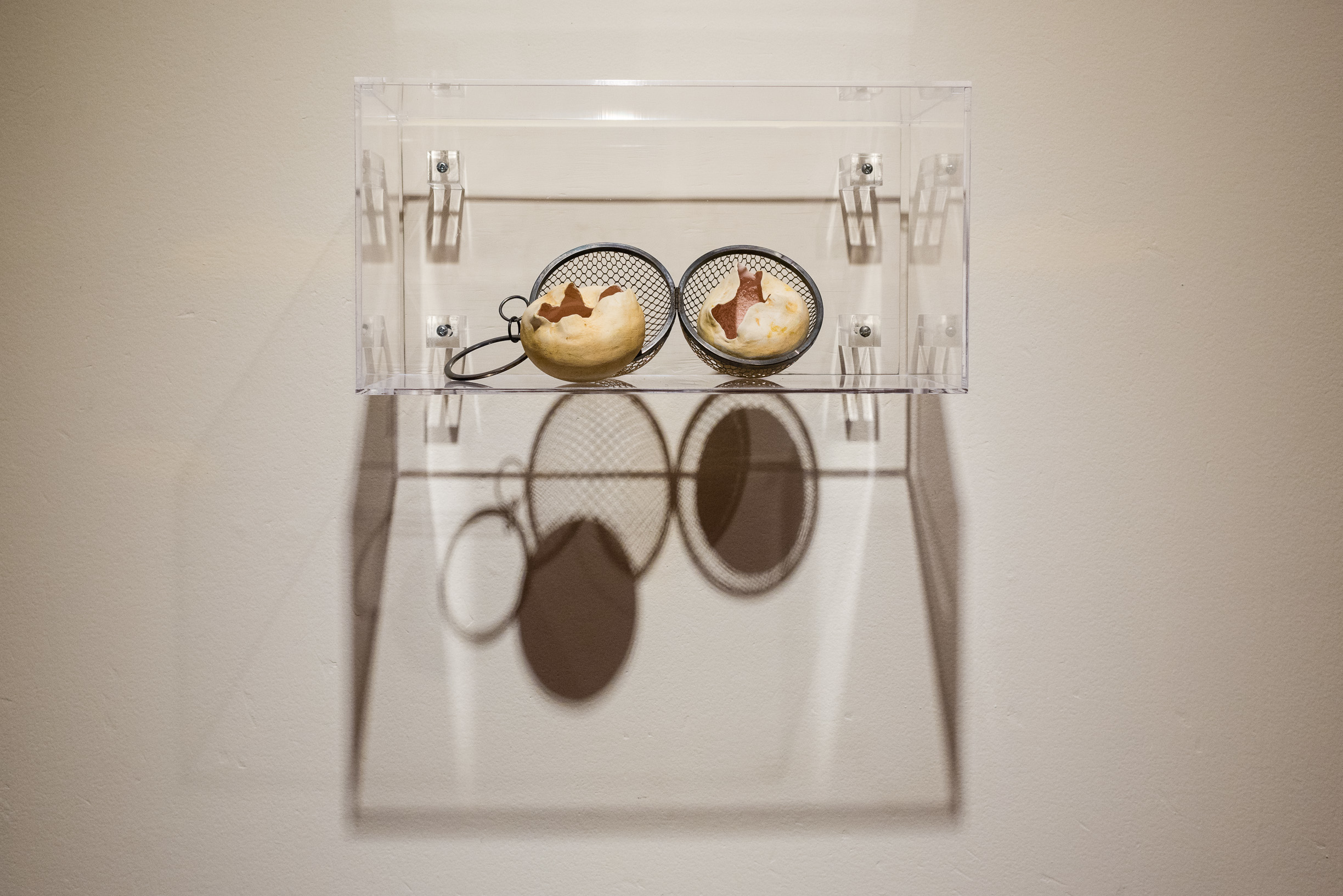

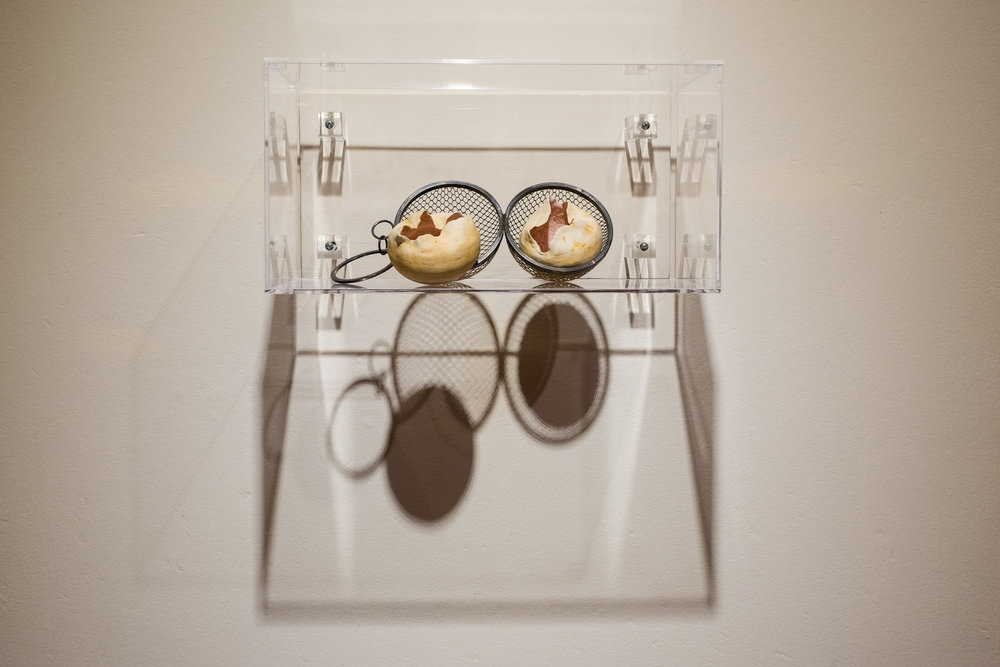

Anina Major. To Have And Not To Own, stoneware, iron and flocking, 16” x 6” x 8”. 2018. This works speaks intimately about the prohibitive and antiquated legislation that policies women’s bodies in The Bahamas. Image courtesy of Dante Carrer. Works courtesy of the artist.

The human body is essential to navigating our experience within the world and, in many ways, art has always been a medium by which we attempt to understand this experience. This is especially true for the female form: historically claimed to be both the epitome of beauty and the source of unholy derision (irony has yet to deliver us), this form has held the attention of artists for centuries. It has been examined artistically – by men – for as long as they were able to put brush to canvas and its rendition often mirrored the societal ideology about womanhood at the time. This process, however, always served to understand the experience of only the masculine: often asserting that seeing this body, creating this body – owning this body – results in significant changes in the man’s experience. The loss of innocence, loss of holiness, to gain true manliness.

This is primarily why a woman’s rendition of the body is so significant. It is essentially the process of reclaiming ownership of ourselves. Major’s creation of To Have And Not To Own subverts this history of masculine control over the woman’s experience. Carefully molded from clay and placed gingerly in and out of wire traps, these egg/ovary-like objects are a result of the careful rumination of unmitigated anger; they are meditations against fear. Within the context of We Suffer to Remain, the piece discusses the trauma inflicted on the Black woman’s body specifically, unearthing the psychological pain that our ancestors once endured and attempting to heal them.

Body reclamation has a deeper meaning for women suffering from the matrix of oppression. In Major’s own explanation of the piece, To Have and Not to Own “specifically speaks about the parallels between the slave master’s ownership of the black body and the current rights of the woman within marriage [in The Bahamas]”. We see this parallel in the debate surrounding the creation of a marital rape law: The Bahamian government’s refusal to legally affirm a wife’s ability to sexually reject her husband calls back to a time when a slave woman’s refusal of her master – sexual or otherwise – was illegal. Her imminent death was similarly justified by law. Bahamians against the creation of the marital rape law all repeat the same argument in defense of their position: when a woman marries, she must submit to her husband. Her body is completely his, to have and to hold, till death do her part. It is a slave woman’s lament.

To Have and Not to Own is Major’s attempt to navigate this conversation about ownership. The two orbs are intentionally yonic in nature; its loose folded edges open to its inside, dusted with pink salt that glitters. Molding the vulva, in particular, symbolically exercises ownership of female sexuality, especially when we consider the historical (male, European) censorship of the vagina within artwork, thought to be too obscene for artistic consumption. The suppression of the vagina mirrors the control over feminine sexuality within society and, with this piece, Major exercises her own sexual agency in response to the debate about the woman’s agency within The Bahamas.

Anina Major. To Have And Not To Own, stoneware, iron and flocking, 16” x 6” x 8”. 2018. This works speaks intimately about the prohibitive and antiquated legislation that policies women’s bodies in The Bahamas. Image courtesy of Dante Carrer. Works courtesy of the artist.

However, the eggs are still positioned in and out of an open wire trap. Representing the oppression that women are now attempting to overcome, the caveat is that the trap still exists, and the ability to close around its reproductive capabilities and rights is still a looming possibility. Major does well in capturing the fear surrounding the entrapment of the woman’s body – whether by marriage or slavery – and the fear of regression, despite the feminist progress we have made. With this piece she helps us to come to terms with the dread sparked when we hear these arguments against the marital rape laws. She helps us to remember the pain our ancestors endured when their bodies were literally not their own.

Major’s work in We Suffer to Remain serves to empower other women artists to speak about this experience we have inherited from our ancestors. The conversations surrounding marital agency all highlight the need for more women to rebel in their art,to reclaim their voices and to assert that the collective patriarchy is not entitled to women’s bodies. In the past few months, we witnessed toxic masculinity publicly take more women’s bodies for their own selfish sexual gratification. This type of abuse thrives on the silence it inspires. Major’s voice within To Have and Not to Own softens the virile masculinity that haunts and destroys us. This piece, like all good art created by women, asserts that our experiences, our bodies, are our own.