A Choice Landscape: The Early Work of the Late Chan Pratt

There are a few names that come to mind for us when we think of the quintessential, traditional, picturesque Bahamian landscape: Hildegarde Hamilton, Alton Lowe, Eddie Minnis, Dorman Stubbs, Ricardo Knowles, and the well-collected (but not quite always at the forefront of our minds), Chan Pratt. Landscape painting is quite a contentious genre of painting for The Bahamas and certainly for the rest of the Caribbean region, and this is for good reason. The colonial photography and postcards and paintings of days-gone-by were instrumental in framing and re-shaping the region as an idyll for tourist consumption, and this growing industry would later become the backbone and difficult foundation of many Caribbean economies.

Krista Thompson outlines the way this idealized image has been produced, reproduced, and reingested by the region for almost 200 years in her key text published in, An Eye For the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (2006). Within it, Thompson asks us, and asks landscape painters alike to consider, “If many of these images [colonial postcards] served formerly as quintessential souvenirs of the tropical, the picturesque, and “civilized savagery” for colonists and tourists, what do such objects mean for contemporary residents?”

It also asks us to consider this visual lineage in all its forms, from colonial American photographers like William Henry Jackson, or Jacob Frank Coonley who became a mentor to the Bahamian photography apprentice and later fully fledged photographer James Osborne “Doc” Sands of Eleuthera. All of whom would have been key in their own way in helping produce this changing image of the landscape as we moved from our indigenous environment to one of settlers, slavery and colonialism, to one being manicured to suit a growing tourist interest. We must think of American Hildegarde Hamilton (b.1898, d.1970), whose paintings en plein air or outdoor paintings, in Nassau inspired a generation of artists growing up in the capital. We also are reminded of Abaconian Alton Lowe’s (b.1945) realistic-yet-dreamy depictions in oil, and the now iconic Nassuvian Eddie Minnis (b.1947) who was encouraged by his contemporary Lowe (and who one would imagine may have come across Hamilton in her work), and of Chan Pratt (b.1964) who was then encouraged and mentored by Minnis. This is by no means a comprehensive list but serves as a keyhole through which to begin to look at our history of landscape paintings in slightly more depth – rather than a mere mass of oil paint poincianas.

Pratt had shown an early interest in interpreting and investigating his environment, as seen in a street scene of Nassau at age 16 and a still life of plants and fruit, though the latter isn’t quite discernible in terms of a geographical sense of place. While these would have been staples in the art curriculum of the time and indeed today, they also show Pratt’s early understanding of the architecture, landscape, and attention to detail he would have grown to become known for. While many collectors of his work speak to the joy of viewing his pouis, poincianas, waterside scenes, and the clapboard colonial nostalgia of his mature work, there is a hidden gem in the Pratt family collection that is so starkly in contrast with his dream-scenes of Nassau we have grown so accustomed to that it may be hard to believe it was made by the same hands.

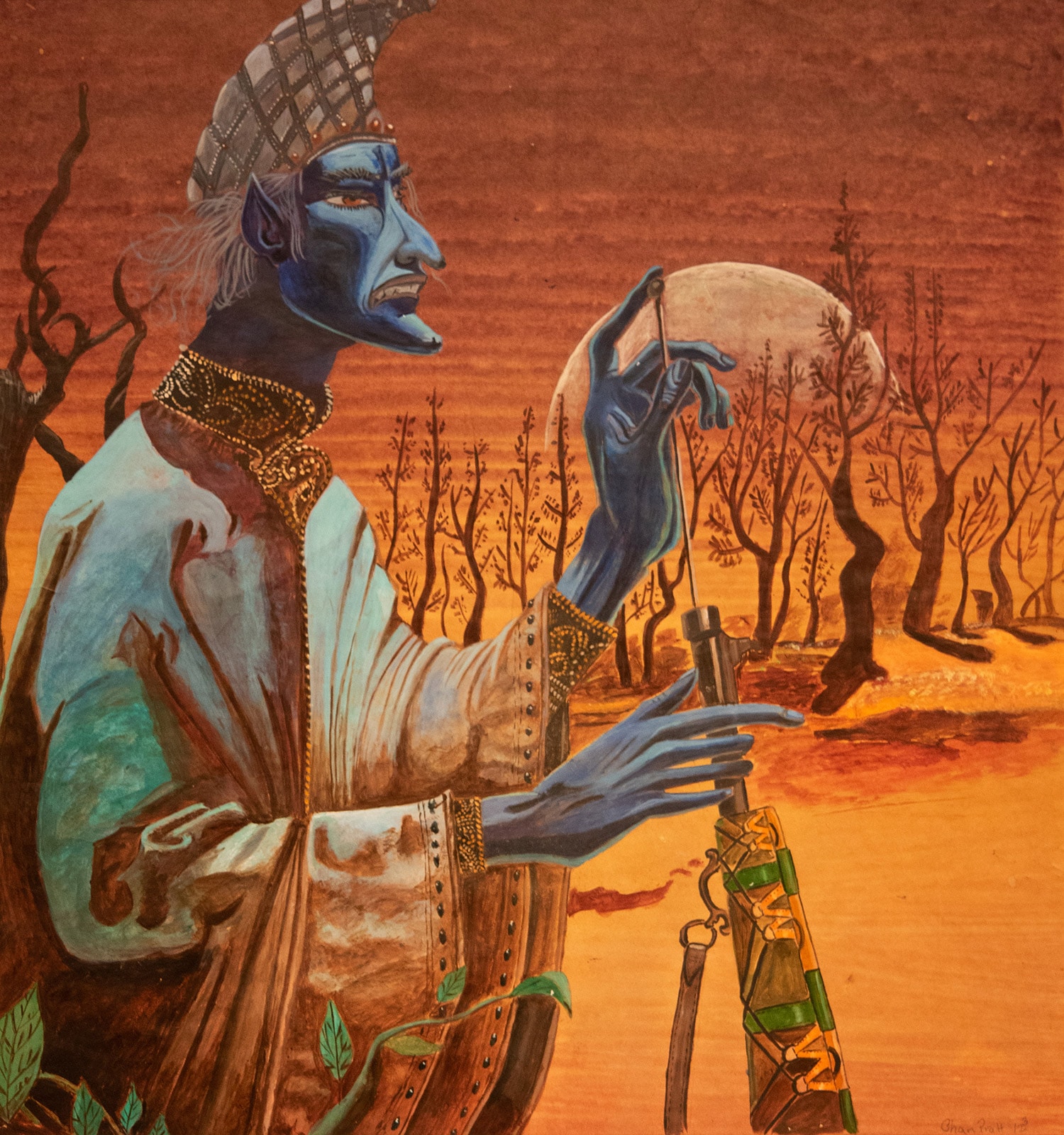

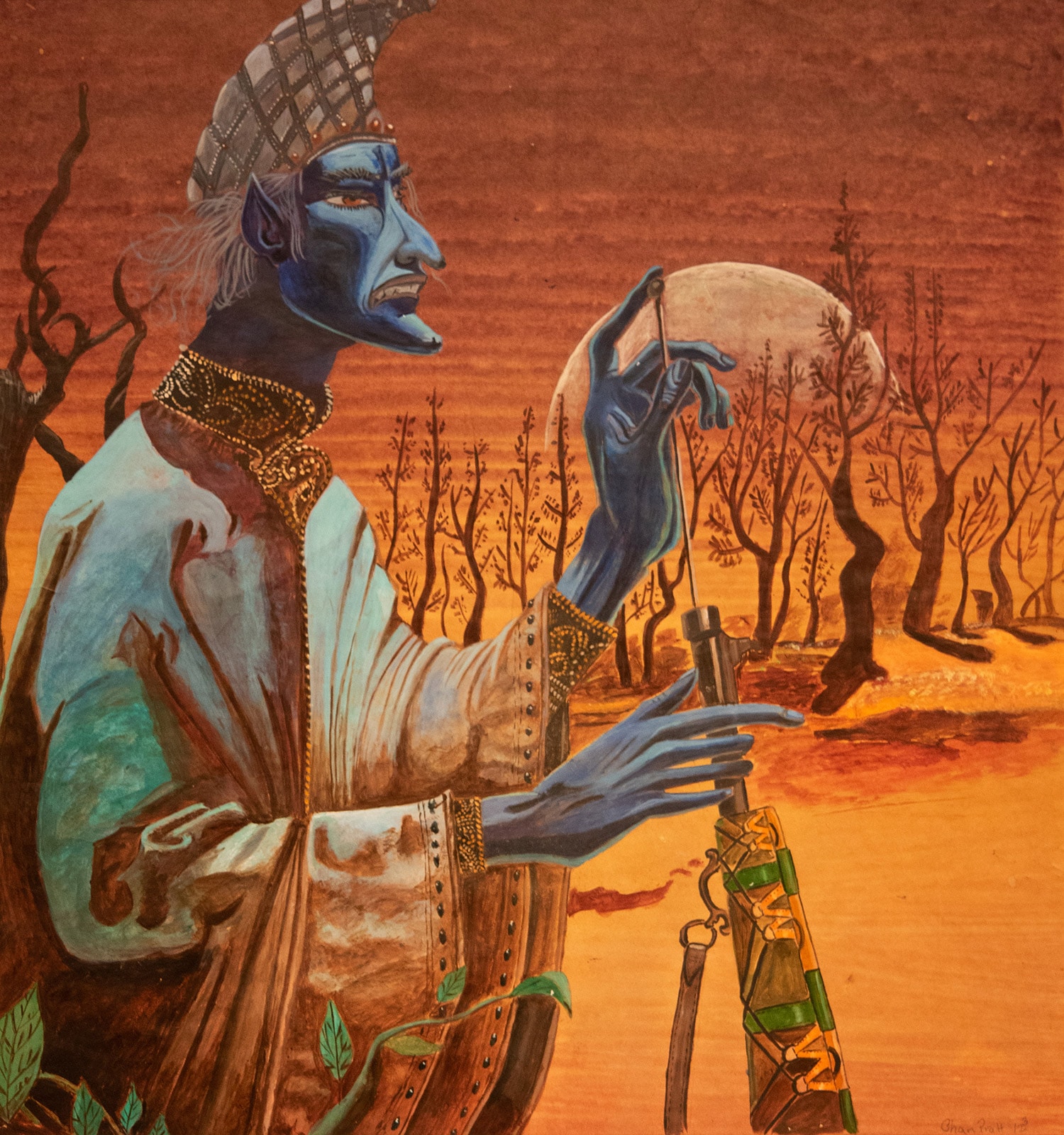

In Pratt’s Warrior God (1982), we see 18-year old Pratt almost foregoing the idea of landscape entirely in favor of figuration – fairly far outside the wheelhouse of the work we know typically of his adult practice. This isn’t the only glaringly obvious diversion, there is also the shift from “realism” (though what constitutes reality is indeed contestable territory in the production of the Caribbean picturesque) into the imaginary. We see a blue-skinned man in a kaftan with embellished detailing, holding onto a rifle. The landscape has nowhere near the same level of detailing nor consideration – it is burnt orange and looks at once like a desert, savannah, and a post-apocalyptic landscape. Perhaps the dystopian undertones are not so surprising as we may think, the early 80s carried with it the Cold War which Pratt would have grown up with on the news, and a year after the creation of his Warrior God he would see the US invade Grenada in 1983 – a melange of Cold War politics and American Imperialism.

When the way we think of this landscape is often to do with the scenic, manicured side of things, it is easy to forget that we do not exist in a bubble of Eden. We drink the proverbial Kool-Aid and swallow our memory of turmoil and living in the margins of American politics along with it – when we aren’t of course dealing with their direct involvement therein. Pratt’s work may deal with the conventional beauty of the islands – though he perhaps had less of a penchant for adorning streets with imaginary poincianas as Minnis had – he was very much steeped in the political configuring and media-posturing of the time as well as his own religious views. Born in a colonial Bahamas that gained independence in his youth, it is naive to think that Pratt’s focus on painting floral and nostalgic landscapes was born of ignorance to the goings on of the world.

The marked shift from his 18-year-old work to the landscapes he quickly began that sustained him later could be due to any number of things: Minnis’ influence, Pratt’s background working in banks and thinking about the art market because poincianas and the picturesque still, unfortunately, have ultimate power in the local marketplace. Pratt made a distinct choice and it is worth considering the various ways that this choice made his career but also pigeon-holed it – still, however, a matter of his own choice. During his later years, he even made a business out of the landscape in the physical realm, taking the 2D painting world into real life with his landscaping business, the Tree Depot. Regardless of his intentions, the undercurrent of the lived landscape is palpable and considered, and not to be merely done away with without context.

Chan Pratt: Resurrection is on view at the NAGB through Sunday, 28 July 2019.