By Natalie Willis.

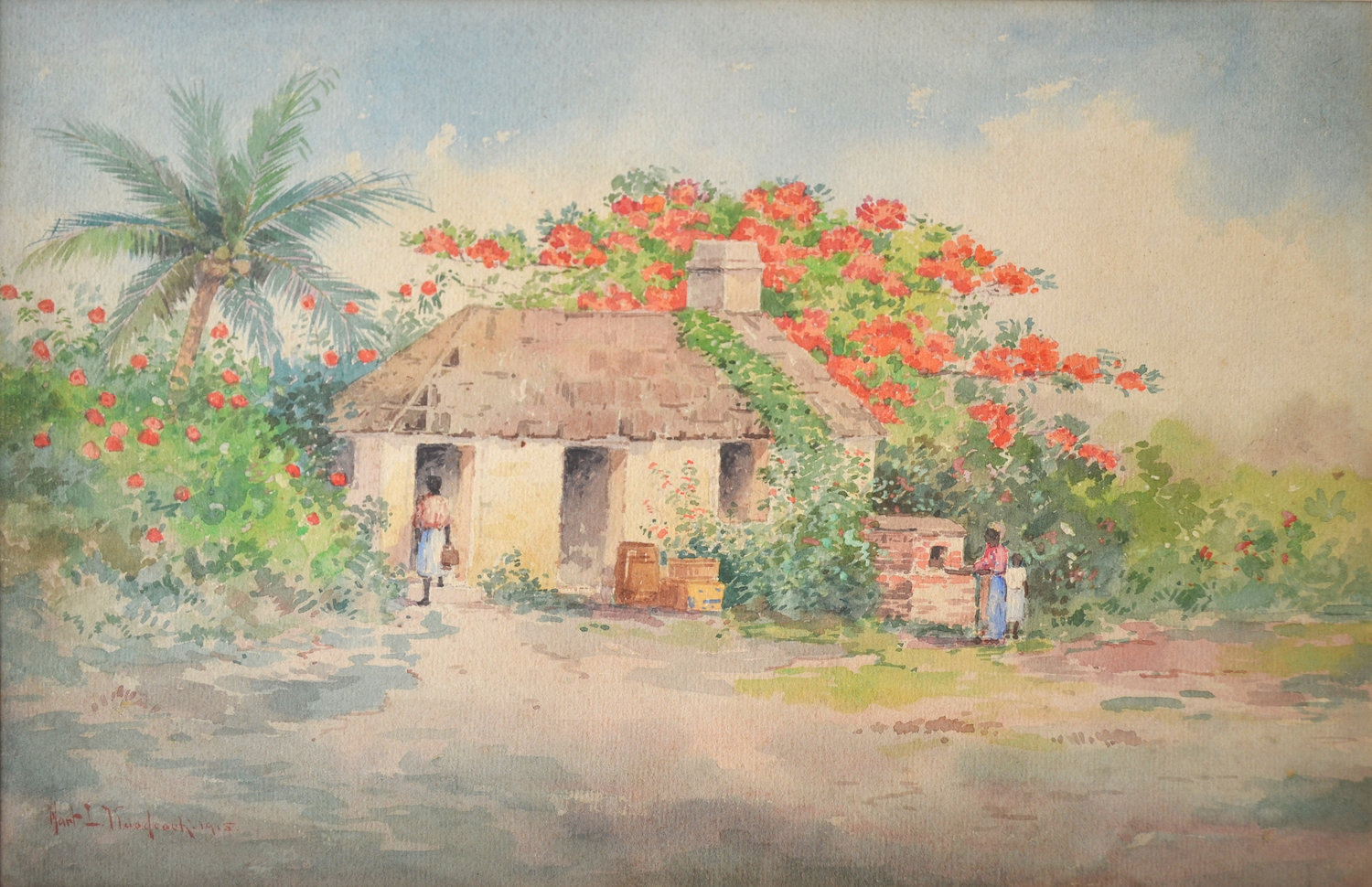

The American watercolour painter, Hartwell Leon Woodcock (1853-1929) is very much one of the typical representatives of British colonial-period painting where The Bahamas is concerned. His quaint depiction of a Bahamian home and landscape – complete with outdoor amenities associated with the time – fits in with the usual canon of charming images from the era. In “Native Hut” (1915) this portrayal of the Caribbean picturesque is precisely why the work was chosen as part of the 2017-18 Permanent Exhibition, “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics,”, and why it is an important part of the National Collection.

It might seem curious to have the picturesque work in the National Collection, given the mandate of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas to promote and preserve Bahamian art. That means the question must be asked: “What constitutes Bahamian Art?” If the nation was formed in 1973, how do American and British travellers, generally producing quaint ‘old world’ charm watercolours in the late 1800’s to early 1900’s, count as “Bahamian.”

If we look to these art objects as things of historical significance rather than something to threaten the socially engaged, visually dynamic work of our contemporaries, we might begin to see how these items help highlight the difference between how we were seen versus how we see ourselves today, as we try to re-inscribe ourselves into a history about us that was rarely written by our own people from the perspective of the people, but generally by someone on a socially-deemed ‘higher’ rank in the hierarchy looking back at us.

“Native Hut” (1915), Hartwell Leon Woodcock, watercolour on paper, 10 x 13 1/2. Part of the National Collection. Image courtesy of the NAGB.

We now aim to dismantle that hierarchy and that history with photo, pen, film, and make ourselves present in three-dimensional vibrancy too. We are the people on the margins whose stories were being told by people in the distance – and not the sort of distance that gives one clarity of a landscape, but rather the distance that renders everything a little blurry, the distance that makes things hard to discern.

This distance is visible in looking at Woodcock’s “Native Hut” (1915) in both the way the subject has been treated visually in addition to the titling of the work. Watercolour by nature implies a sort of transparency given the way the medium works, and there is indeed a certain transparency in the way that Woodcock has rendered his interpretation of a scene from Bahamian life.

Perhaps the most striking in this scene is the fact that it could quite honestly be anywhere in the Caribbean. There is nothing to denote a distinct sense of Bahamianness, despite the fact that Woodcock was approaching this with the wisdom of his later years in life and also despite the fact that he had indeed completed other paintings with scenes that showed iconic Bahamian scenery. Woodcock’s reduction of the landscape and removal of a horizon to give us a sense of place help speak to this distance on a level of ‘us’ and ‘Other’. The poincianas and palm trees that have become so indicative of the region are present, but the land in this image does not exist outside of these plants to give us a generalised sense of place, and the home pictured center. Even the faces of the people shown are lacking distinction and the skin colour, paired with this lack of features, means these women and child could be anyone on the demographic of people of colour in the region: Black African, East Indian, the descendents of either, any creole or mix-heritage thereof, and so on.

Installation shot of “Native Hut” (1915), a colonial-era watercolour by Hartwell Leon Woodcock, as seen in “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics”, the 2017-18 Permanent Exhibition.

Further, the use of the word “native” in the title is also particularly loaded and indicative of the time. The black population of The Bahamas at this time was still very much suffering from the segregation and systemic racism associated with the time. Though this was after the abolishment of slavery, the effects were still very much fresh and felt, which is easy to imagine given the remnants of the era we are still being forced to reckon with now. The term was always a misnomer, as the word is indicative of a sort of indigeneity that we simply do not have in The Bahamas, and lacking in much of the region as a whole – largely thanks to Columbus and his first wave of colonial activity which, as conventional wisdom has it, wiped out the Arawaks and Lucayans.

This home he has depicted – loosely and, yes, beautifully – also lacks depth in itself. This feels very telling, in retrospect, as it is in many ways a way to show the traditional lack of origin many Bahamians and Caribbean subjects feel as a whole given our difficult history and lack of indigenous peoples. What does being “native” mean to us truly? People have been stripped of their identity in terms of face, even distinctness of place, and the whole painting looks a little bit like a dream, which is—again –very telling of the way the place was viewed at the time. The Caribbean was an idealised Eden, a place full of compliant “natives” even after the commercial practice of slavery was eradicated, like a ‘bad dream’ from which we suddenly awoke.

“Study of Pink Dress” (1999), Thierry Lamare, watercolour on Twinrocker paper, 17 x 11. Part of the current “Thierry Lamare Retrospective: Love, Loss and Life” on at the NAGB.

The distance of Woodcock from his subjects, as you can see, is revealing of the period in many ways more than the artist. Amelia Jones, an American art historian, critic, and curator, discusses in her 2003 essay, “Feminism, Incorporated,” the way that the theory of the “Distancing Effect” of the German playwright Bertolt Brecht can be applied to painting practice, primarily in the way this affects postmodern paintings. The “Distancing Effect,” also known as Brechtian distanciation, is, as Jones states, the “[aim] to make the spectator an agent in cultural production and activate him or her as an agent in the world”. It is that phenomenon in which the audience is presented with a situation that removes them slightly, to then imply a sort of objectivity with which we can re-interpret the situation in front of us in a new way. It serves to remind us that we can, and should, be critical of what we consider an ordinary or everyday experience, things we take for granted.

Simply put, it helps us take a step back to re-assess what is happening. It is an implied, perhaps false sense of objectivity that helps us to not quite take the world as default. This is the sort of distance we perhaps see in Thierry Lamare’s watercolours, in which he re-presents our traditional ways through painstakingly accurate portraits of women who we know could be any of us ‘back in the day’. The portraits are often confrontational, in a way, with the women facing you head-on, directly meeting our gaze – an effect often employed in classical paintings by ‘the greats.’

Installation shot of “Study of Pink Dress” (1999) by Thierry Lamare as seen in the current retrospective of his work, “Love, Loss and Life” at the NAGB. Image courtesy of the NAGB.

Both Lamare and Woodcock are watercolour artists of European nationality or descent who made the choice to move here, live here, visit here, but the attitude towards subject is incredibly different. Perhaps it is because of personality, in some regards, as Lamare has a keen interest in knowing his subjects and muses on an intimate level of friendship and closeness before he paints them, but perhaps it is more indicative of the time.

The colonial era, as we know, did not encourage the social mélange of people of colour with Caucasians, the social hierarchy was established, and this time in history is why Woodcock’s “Native Hut” (1915) has the distinctly un-Brechtian distance it does. Perhaps if he had felt inclined to venture inside this hut, to share a meal with the women working the outdoor oven, the work may have turned out differently.