By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

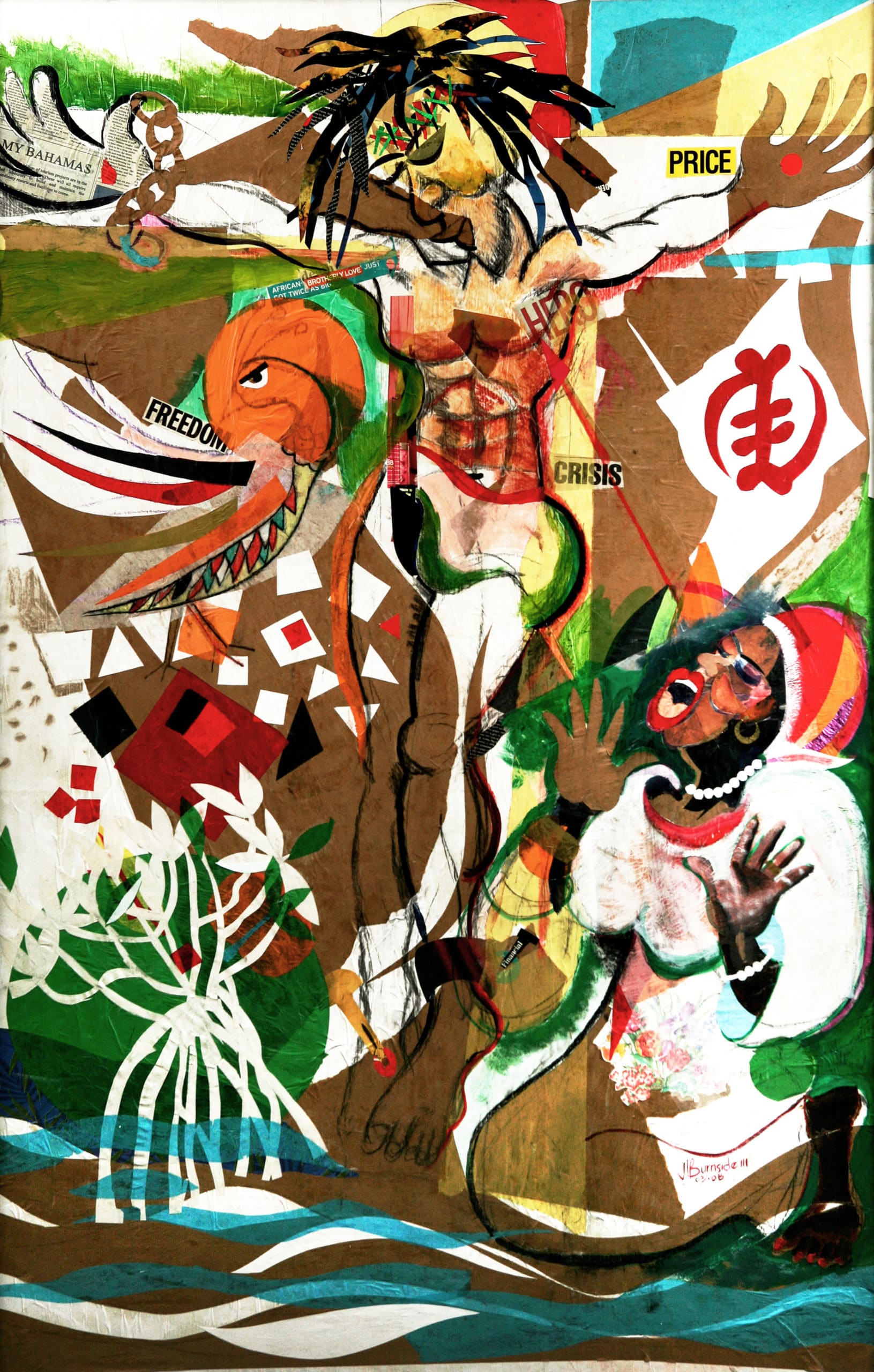

Colour, movement, connection, difference and texture are all words that join to make meaning. Though Jackson Burnside’s “Omnipotence” is huge without imposing itself, it approaches the familiar and reflects what we do not talk about. In reflection, as the theory goes, there should be distortion but here the reflection captures the being of spiritual materialism in Bahamian culture and psyche. There is hardly distortion, except to underscore the distorted view we have of ourselves and our endeavours.

Rasta, not accepted; flowers, ignored. One day at about 7:30 a.m., frustrated by traffic as usual, in a holding pattern, while driving across Boyd Road, there was a little boy in his school uniform, watering crocuses that lined the base of a cement wall that partially enclosed the house he must have inhabited. For many, they would have missed him, his unpretentious unannounced act of watering flowers would simply go unseen because we are not looking for that.

We are in the heart of what has been ghettoised. It is no longer a cool place to reside, no longer middle class for ‘black’ dwellings, no longer under the hard and heavy hand of colonial segregation and policies of international development. That young boy held so much of the resilience that we deny to so many aspects of African spirituality; including the tenacity of Blacks to survive the intentioned and pragmatic sanitising of their beings. Through the many different approaches that were used to deny the worth of Africa and any African derived artefacts and souls. Howard Johnson articulates this in his work on Bahamian history and identity.

The colour and the dance of Burnside’s piece butts up against the intentioned yet static space of the written word. My Bahamas caught up in the movement of life, losing itself to whatever international landowning and capital projects have in store for the bodies that inhabit this place. Dreadlocks are terrific as they hold wisdom in words woven into their textured–yet unaccepted—“no hats, no plaits, no entrance” Bahamian policy of dealing with Blackness. The tribes of Rastafarianism all equated with one. Blackness despised by a white-aspiring, holy group of double-conscious, northern focused eyes, gazing up at high-ceilinged buildings where the public may pass through, but are not truly welcomed.

Green spaces beyond the Southern Recreation Grounds are not for these souls. The space of spiritual rejuvenation for no one other than Anglicans, in a pinch, Catholics and—much later and more begrudgingly—Baptists who were always too zealous.

The Mama Inez, Shango Baptist, Caribbean Mama figure omitted from popular images of Blackness through the American South’s mammy, yet an essential figure in Black identity because of her matriarchal position in the family and the community. This is where one went to discuss all problems of every nature. In a Puerto Rican context, the Mama Ines figure has become tightly associated with the Yaucono brand of coffee, totally co-opting her other identity. Significantly, Black women have held large sway in the Caribbean and the images of mothers, grandmothers, spiritual leaders, and resisters of oppression–Nanny of the Maroons in Jamaica–whose legacies remain national, but whose identities have ironically been flattened out by a deeply duplicitous nationalist project that is at once liberating and controlling, patriarchal and claiming matrilineality Africanness. The movements of Negrismo, Black power, “Negrista” poetry–specifically in Puerto Rico, Afro-espiritismo in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, though deeply divided by dictatorship and torture, under Trujillo, who saw fit to sanitise the DR of ‘Blackness’ pays further testament to this erasure.

The apparent distaste was for Haitians coming in and taking jobs, though they had been sought after sources of cheap labour since the ‘50s, mostly included those who didn’t perish under these violent and dictatorial massacres. With the exception of few ‘newer’, ‘younger’ women writers who would have come of age in the 1990s such as Edwidge Danticat and Julia Alvarez, without whose voices, much like Burnside’s images, stories would have been silenced.

The political uprising in Haiti was directly influenced by the deeply spiritual reasons why Blacks did not want to remain enslaved and refused to be subjugated. Though, we must underscore that most of the movement—as was also the case in The Bahamas—was not ‘owned’ exclusively by good Christian, Church-going dark-skinned Blacks, as history would have us believe. They were times of strife and struggle, and the details have mostly been forgotten.

The movement in Burnside’s work, the statically printed word, collaged in the centre while being denied primacy though perhaps taking it, speaks to the deeply spiritual and mystical time. Why do we divorce Christianity from spirituality and mysticism? When did this confluence become unholy? Burnside’s piece reminds me of that young boy, only doing what he does to be here and to see beauty in his neighbourhood, in his home. The colours in the work are not matters of happenstance; they are focused and meaningful as well as meaningfully placed around the price and crisis that undermine freedom. The browns, the greens, the reds are all deeply spiritual and rooted. Problematized by the chains binding the Hero–cast as villain–crowned with thorns as the mother, matriarch, reminiscent of Winston Saunders’ play You can Lead a Horse to Water (1998), the Christ-like figure gives his life for others. Orlando Patterson’s text Children of Sisyphus (1982), Roger Mais’s Brother Man (1954), are similar to the caricatures of the Black woman misunderstood and maligned by a deeply needed but flawed deliverance from colonialism and suffering.

When the Middle Passage occurred, it marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new reality. With its disavowal, we allow the remembering to be disjointed and by killing off the dreams that led to overthrowing oppression. It could be said that Burnside’s “Omnipotence” speaks to a vibrant overstanding of the ‘absence of ruins’ that nationalism has left for us to mourn in the wake of erasing memories. Burnside’s piece moves through so much of the promise and the loss we have lived, but the hope we always have, as we must water our flowers to see beauty.

Once the soul, the spirit, the creativity and the being is ghettoised, this is little hope that can rise from the dungheap of history. The Ford assembly line of labour remains very much alive; only we cannot see it as it hides in plain sight. Art survives and transcends these historical glitches that allow the past to re-enslave the present.