The recently opened 8th National Exhibition (NE8) contains much of the Bahamian art we’ve come to know and love over the years. We are a nation and a region with a very strong tradition of painting and wall-based work, which has expanded into the 3D realm, which we have also grown increasingly comfortable with accepting into our arsenal of Bahamian creative practice. But we also have grown into more expanded fields of engagement and display.

NE8 at Hillside House

Socially engaged art practices are nothing new, and arguably they mark the start of modernism in art: work that uses the stuff of politics as material. This itself perhaps started with painting but socially engaged art as we know it is the product of the last 70 years or so. This kind of work is a bit harder to pin down as art if we aren’t aware of it. How can actions be art? Well, that’s easy enough to think about with things like performance art or dance, we get that. But human interaction and activism as art?

These things are a bit slippery for many of us, despite the fact that this kind of work has been going on for quite some time now. The art world we’ve inherited is, of course, the product of the past two centuries of art – not at all like the work that has existed for the past two millennia, or even the past 20. The art world we know is, of course, tied up in the art market, which has understandably complicated our relationship to work as people who make art and as viewers: do we make to sell? Do we view to tap into that sense of grandeur? Some do for certain, but it is out of these conditions – and the elitism that many find inherent in contemporary art as it relates to the art market – that socially sensitive projects exist, in part at least.

Art and activism have developed quite a happy marriage over the past few years, and as we have seen recently from the impact of social media coverage of art and comedy social commentary, it would appear that where the mainstream media has failed us, in some ways the ubiquitousness and accessibility of social media has provided a way to bypass ‘the powers that be’ and spread news of fantastic projects that we mightn’t ordinarily hear about.

Artist and Researcher in Residence, Hilary Booker.

Artists and theorists and philosophers alike want to write marginalised peoples back into the centre; there is an urgency in this, and it has only increased its energy and trajectory since these ideas – primarily driven by postcolonial and cultural theory – gained widespread attention in the late 80’s and 90’s. Further, work of this kind is so utterly important and necessary for the Caribbean and has been the bed on which so much of our art as a region has been made. In particular, we can look to two projects in the NE8 that explicitly deal with these ideas. Hilary Booker is the first Researcher/Artist-in-Residence for both the NE8 and Hillside House as part of its new programme to create a space to nurture the production of new works. For the next four weeks, she will be sourcing and creating plant-based meals using mostly local produce to help us re-engage with our environment through food.

‘The Moonflower Room’ – her new framing of the space at Hillside House- will be a way also to help us reframe how we view our food practices in relation to knowing ourselves as Bahamians. “I am most interested in looking at the intersection between the intentional food practices of people in Nassau and their spiritual journeys or journeys of consciousness, and how people’s very material everyday, and the most mundane thing that people do every day, actually translates into people’s sense of who they are and desires for decolonisation and healing spiritually, physically and emotionally.”

Booker quite clearly understands the importance of food not just to Bahamians in general, as we so often joke about how much we love to eat, but how food functions for us in social contexts, and the capacity of sharing meals for eliciting a sense of emotional wellness as much as physical. Some might not immediately see the linkage between creative practices and scientific ones, and it must be noted that Booker has just completed her doctoral research in environmental studies. But her keen interest in the community, in people, and in using creative platforms to think about data shows how utterly necessary such a holistic approach is.

Science is never removed from life and can never exist in a vacuum, despite the myth that we can be objective as human beings in looking at data. We all process everything we come across based on our past experiences, and science is no exception. Just as science cannot exist removed from our experiences, art deals with the material of it in much a similar way. “As an interdisciplinary artist, I’m interested in environmental studies, so I’m interested in looking at the people and Ecology. So much of this project is about merging the beauty of the two and looking at the ways that the ecology effects and develops the culture. I want to find a way to reflect this beauty that I see back to everyone.”

Dealing with our post-colonial condition and, as Booker says, our desire for decolonisation can be such heavy work, but she frames this project with a spirit of hopefulness that is impossible not to believe in. On talking about the inspiration for the title of the project, she shares “In a simple way, a moonflower is a plant that has an incredibly intoxicating fragrance and it blooms in darkness. For me, there is something about that idea, that there is this beauty that is presented in darkness, that blooms at night-time. To be able to express beauty even when there are so many challenges and in a situation that you wouldn’t think suitable to sustain it. And aside from that, it’s also a plant that is often used in indigenous cultural and medicinal systems and it is an extremely potent. I like to think it works as powerful medicine on both those levels.”

So then, this asks several questions on this kind of work: Is the action the work? Is the presentation of information the work? Is it the connection of people? Is it the creation of a safe spaces or spaces of catharsis? Or can it also be a question of representation? Whereas Hilary’s project deals explicitly with our connection to food and colonial heritage and how the environmental and social ecologies of The Bahamas are affected by this history, The Commission of the Queer deals perhaps most obviously with a need to be seen and be heard when you have been marginalised.

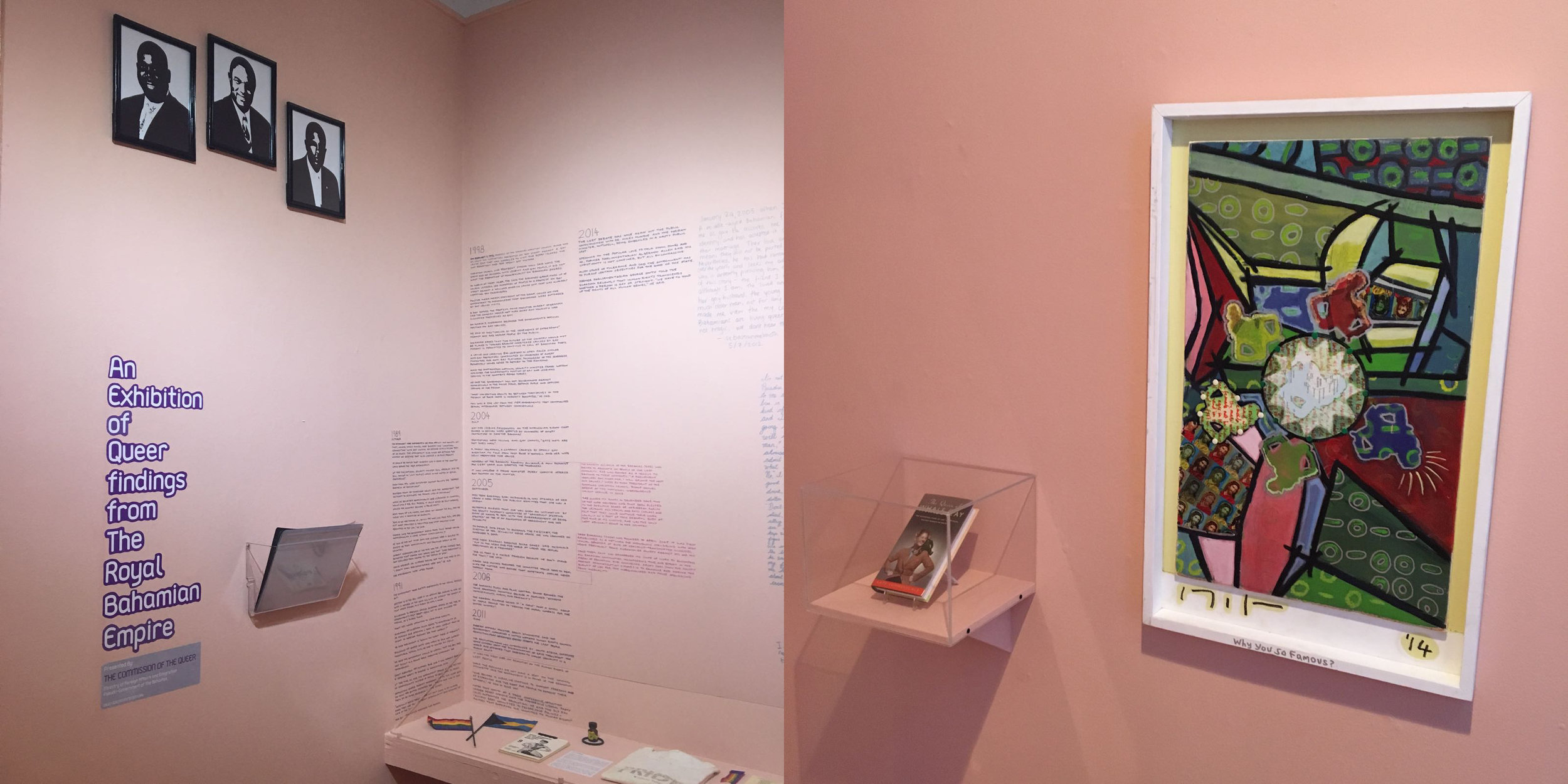

Installation view of artefacts and artworks from An Exhibition of Queer Findings from The Royal Bahamian Empire organized by The Commission of the Queer. Images courtesy of Jon Murray.

The Commission of the Queer (CoQ) shares with us the experiences of Bahamians who identify as queer – be it any part of the LGBTQQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Ally) spectrum. And while it does deal pointedly with the experiences of those who have moved from our islands elsewhere – for refuge or otherwise – it also tackles the difficulty of existing openly here and trying to navigate this space. Jon Murray, who is part of the collective, speaks of the difficulty in not only providing the right language for us to speak about queerness but also to speak about this kind of work. “I don’t even know what word to use for these kinds of projects: agency, entity, organization.

All of them seem very restrictive when I’m viewing it as this network and connection and web that is living and growing as it needs to. Whether that’s growing bigger or smaller, time will tell.” They are just that. This is perhaps why projects such as these are so hard to pin down. They don’t exist in the way that we think of artwork. “To think of social practice as a living thing is the best way to approach it. I feel that with autonomous artworks they have a potential for timelessness in the presentation of the image – or whatever other form the work takes when it is presented. They’re more like snapshots from a film instead of the film in its entirety. But with a project like this where people have to be brought to the table to create dialogue, it can ever be truly finished. It makes the work a living thing. It can last a long time; it can die off and come back. This is what relationships are, and this is what these works are made on.”

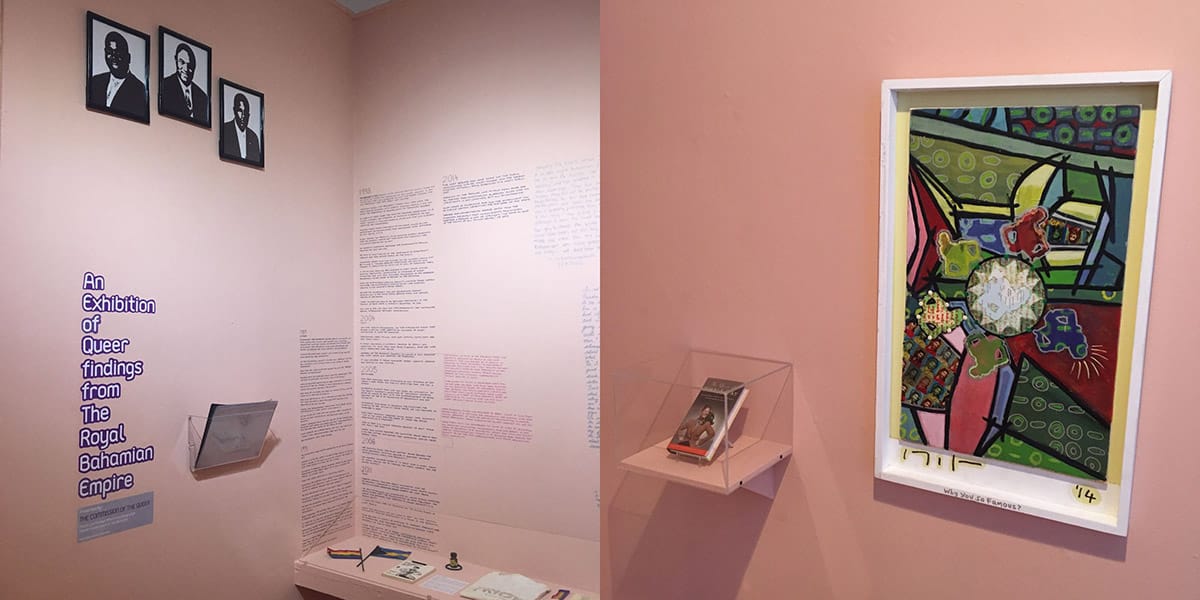

Margot Bethel’s “Why You So Famous?” 2014 as seen as part of the presentation of The Commission of The Queer in NE8.

Another question gets posed then: what is the capacity for change with social practice as art? “I think change is implied, or even unavoidable. This type of work is about building connections and creating connections between people, so I think it can be an act of providing representation, by the act of simply doing that in itself. In the pure sense of social practice as artwork, where you’re creating a context in which people work toward something or interact, through that context and situation there is a faith in the project that change simply has to occur.

I think that by doing one (providing representation), you’re doing the other (change), and they become interchangeable in a way.” In a year of such intense political tension, the creation of safe spaces and spaces of healing and wellbeing are paramount. The change began on Thursday evening, December 15th at the NAGB, and starts today, Saturday, December 17th at Hillside House. The National Exhibition 8 runs through April 2017.