By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett.

Art is a well-known document of history. All types of creative expression chronicle the moment they depict. Portraits, much like those on display in Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid are examples of this, especially the Goyas, for example. This column chooses to focus on the interlocking of art and history: “Art History,” its learning and teaching. So much happens in this somewhat fraught intersection between art and history, especially in a country like ours, where scant attention is paid to culture, except for its commodification and consumption.

As a part of a history course on race, class and gender in The Bahamas, students attended a number of discussions at The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and walked around Downtown Nassau to see first-hand where history was left to crumble and collapse. It is ironic that we continually argue about attracting tourists to our shores, yet we are thrilled to see history fall around us. One of the major attractions that draw people to this small country is that it is the landfall of Columbus in 1492. We seem unable to connect the dots when it comes to privileging stories and experiences, even when not beneficial, so that they promote local development and empowerment.

In 1992, the Dominican Republic, especially Santo Domingo, made millions of tourist dollars by focusing on the landfall and presence of Cólon, even though theirs was not the point of ‘discovery.’ Today, The Bahamas is discussing pulling down a statue of Columbus that attracts thousands of tourists a year but yet has done nothing to own the Geographical Indicator of Columbus’s landing, allowing Cat Island and San Salvador to fall into a state of national embarrassment. People continue to claim modern-day San Salvador as the landfall point, though everything points to the contrary. In fact, Cat Island was the actual San Salvador of the time, its name having been changed at a later date; this discussion has had little traction locally, although a historical fact.

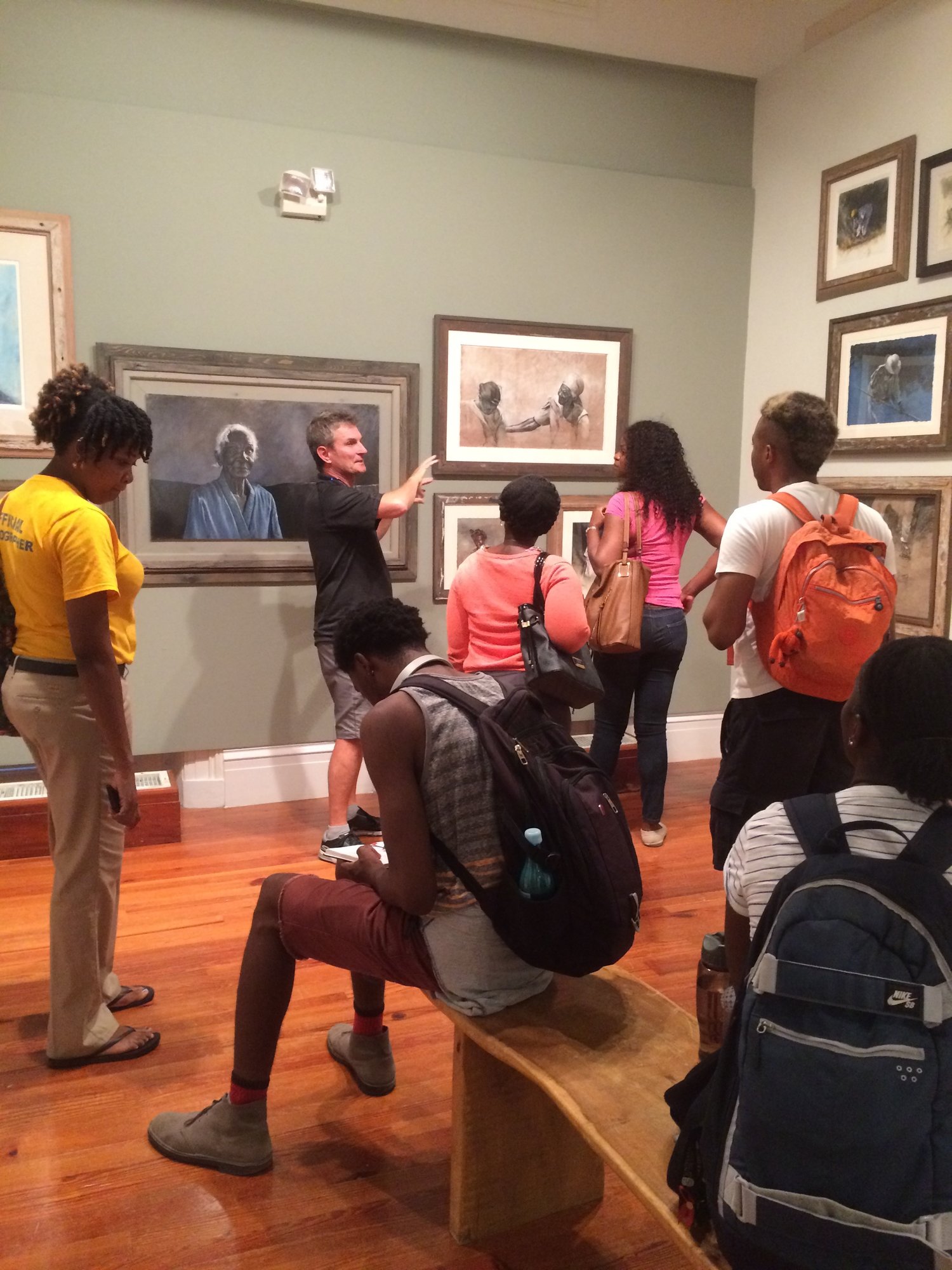

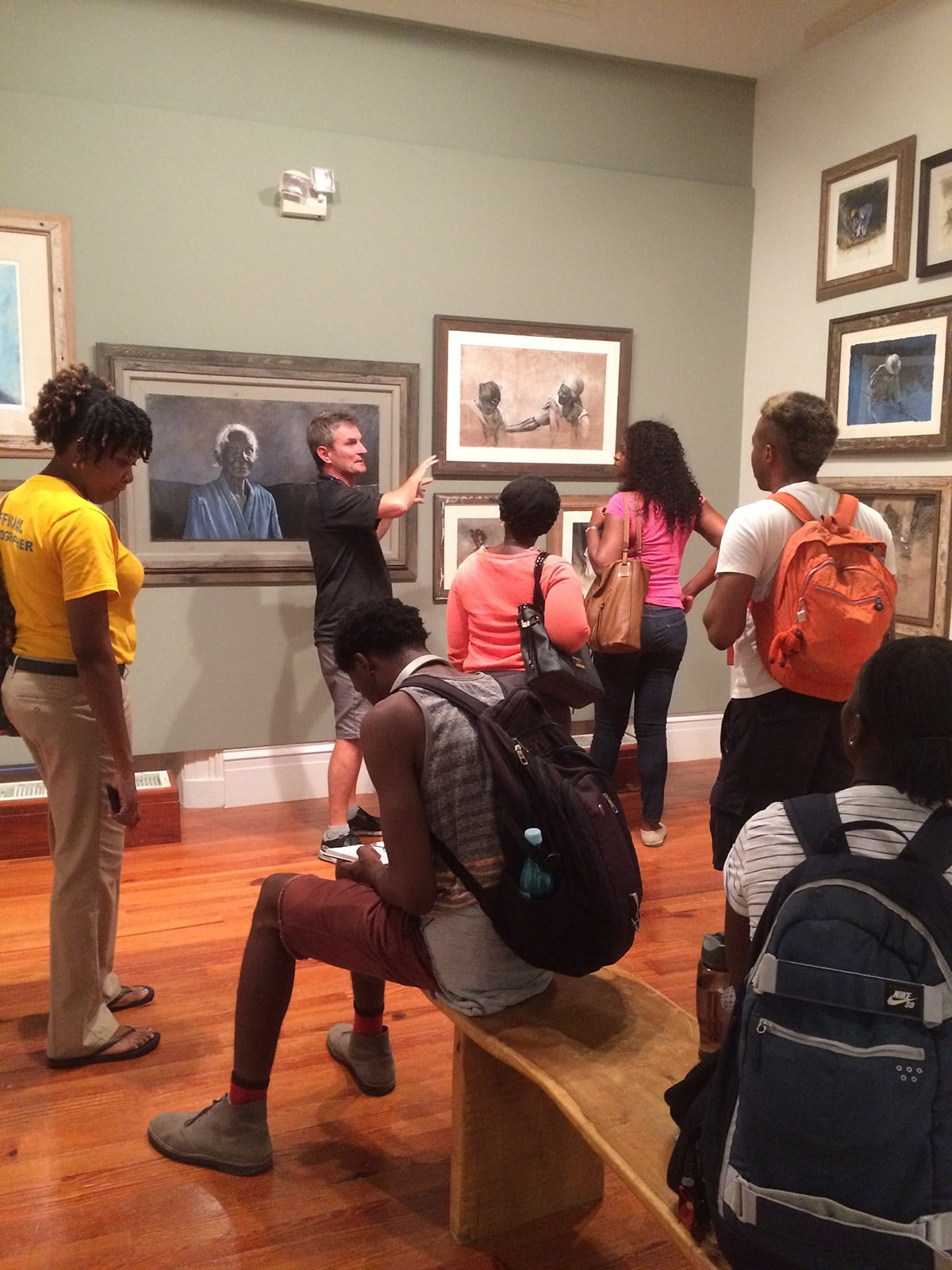

University of The Bahamas students visit Thierry Lamare’s “Love, Loss and Life” on view at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and receive a guided tour by the artist. Images courtesy of Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett.

At the same time, so much must be said for the manner in which art documents momentous occasions in history. This was focused on by Thierry Lamare in his exhibition “Love, Loss and Life,” currently on view through October 22nd at the NAGB, when he shared with University of The Bahamas students during a part of the History course taught during the summer. The class spent a morning with Lamare, and he walked the students through his work from beginning to end. It was an incredible experience for these students, who had been encouraged to engage with art and culture as vehicles to understanding how Bahamians think of and live with race, class and gender issues. It was a brilliant experience because so much that is never discussed, never dealt with and never touched upon, but that lives and breathes under the surface of the ‘Bahamian psyche’ was visually unpacked in the work.

To begin, Lamare opened himself to the students with stories of his work and life. He discussed his close relationships with his subjects and the loss he felt when they left this earth. The rendering of art always creates a relationship between subject and artist, even though we cannot always see it. However, what also springs from Lamare’s work is a capturing and documenting of a way of life that is rapidly vanishing.

Lamare hones in on subjects and captures them in extremely natural moments of their day-to-day lives and shows how he builds his artistic document over time. Further, he shows Bahamian sloops and fishing boats that are rapidly disappearing from the Bahamian landscape. Meanwhile, we can still find Haitian sloops in the southern Bahamas, docked at Matthew Town, Inagua, by the way. Bahamian sloops are passing away, much like many traditions as the time and space to practice these skills and special crafts are being lost.

The discussion with Lamare was a rich space for the students because of his willingness to share and his generosity. His brand of realism captures the soft textures of island life on Long Island; his generous spirit is also seen in his relationship with his subjects, Ophelia and Joyce, who he paints in various places and through various studies. He painstakingly though effortlessly walked the class through his steps and stages as well as his experiences while painting his muses. Art captures life and Lamare’s work provides a realistic rendering of life. The students were enraptured with the experience of walking through the gallery, being exposed to the work and having the “inside scoop,” so to speak, on the creative process.

University of The Bahamas students visit Thierry Lamare’s “Love, Loss and Life” on view at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and receive a guided tour by the artist. Students ask questions and take notes of the images on view.

So much of what we experience is predicated on race and class, yet we do not notice this. Further, our national work on historical representation often falls short because we ignore the obvious. Lamare’s work, while deeply depoliticised, becomes a testament to race, class and gender in the Bahamian context, not only the Nassau or New Providence experience. We, as Bahamians, also often ignore or forget the complexities and differences of lives lived outside the capital, the more porous boundaries of race and class that would have operated in various communities and the verisimilitude of art and literature that brings life home to us in touching ways.

In Cuban Spanish, there is a saying that has stayed with me, and it says, “lo que bien se quiso, nunca se olvida” meaning: “that which is loved deeply is never forgotten.” In the relationship between artist and muse, one can see this. In the history of The Bahamas, one can see the great pains we have gone to as a nation to erase our past, an effort to deny the hardships of the past perhaps, but a dangerous trend that only allows the vagaries of political and social corruption, to reinvent themselves in the space where erasure has wiped out memory and experience. One irony, though, is the cellular memory that the body has for all experience, even when not lived first-hand.

This walk through art, its depiction of local lives and history and the walk around downtown where history, a part of the local story, a lived memory is left in tatters by governments ever since independence, now it has almost forgotten its abandonment and neglect because it has been unloved and uncared for so long. The best way to kill anyone is to ignore them. The students who vacillated between indignation, anger and disappointed sadness at how little of their history they knew and how much was ignored, often sat stunned by the killing of the Bahamian stories. The time spent with Lamare gave them a different kind of voice and allowed them to see a window that opened onto lives that they could identify with.

Certainly, our need to teach Bahamian history beyond the Tainos, Loyalists, and Slavery is clear, but also the need to move the country into the 21st century where the UN is perhaps the newest global leader and pacesetter and where their agenda apparently determines how we live in our skins. Our stories are being lost, not only because we do not appreciate history but also because culture is seen as something twee that can be packaged and sold. When government workers can argue that to copyright our heritage is trivial and so not worthy of focus, we are in peril of erasure. Perhaps this is why history and our story is not taught in any meaningful way in this system; it might serve to empower.

The walk through history, the authenticity of realism and the gentle, kind hand of an artist who illustrates his muses and willingly shares with students brought so much our life, stories and essence alive. The free-flowing energy, talent and experience as shared provides hope that at least one small part of the story will survive in the young people who experienced this exchange.

History is not confined to dates, places and notes penned by a colonial master or secretary depicting a subject, but also the art of their day-to-day lives as brought to light by a living facilitator, the artist; history is about people.

Due to popular demand, the exhibition “Thierry Lamare: Love, Loss, Life” has been extended through October 22, 2017. The NAGB is open Tuesday through Sunday and is FREE on Sundays for Bahamians and local residents. Go to www.nagb.org.bs for opening times.