By Patricia Glinton-Meicholas

Its foundation announced in 1996, The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) was officially opened on Monday, 7 July 2003, which means that it is still a youth as art museums go, still engaged in defining its identity. I envision for it a plum role, ready for the plucking from a fertile tree of a people richly endowed with creativity. The Gallery can be an important builder in the development of people and nation, employing a diversity of creative impulses of artists, exotic and indigenous to “story” The Bahamas, providing a mirror to prompt Bahamians to take a deeper look inward and bear even greater fruit.

The Gallery is well positioned to seduce Bahamians into discovering and valuing a truer history, heritage, culture, fault lines and, indeed, art and its real genius, so often buried beneath the refuse of infantile politics and the marketplace, or asphyxiated by its own narcissism. To this end, it must appreciate that, like The Bahamas itself, its identity lies, inextricably, in concentric circles formed by its landmass, its history and its relation to its nearest neighbours and the wider world.

Famed filmmaker, Fellini expressed this layered nature brilliantly, “All art is autobiographical; the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.”[1] I am decidedly in agreement. For the oyster, as well as the conch of The Bahamas, the pearl springs from a painful irritant in the flesh, which goads the animal to heal itself. It does so by coating the grain of sand with a nacreous fluid and, thereby, pain transmutes irritant into luminescent beauty.

This fortuitous positioning exposes how Bahamian artists have been among the leaders in negotiating the redefinition of Bahamian ethos and identity.

The NAGB and others who offer critiques have begun to formulate the aggravating element for pearl construction by a still embryonic juxtaposing and contrasting exhibitions. It is a process that could produce valuable growth in Bahamian self-examination generally, if it stimulates a more incisive exploration of the thematic material to put into stark relief underlying meanings unintentional and intended. Four 2018 exhibitions have borne great promise “Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value”, (March 22-July 29), “Hard Mouth: From the Tongues of the Ocean” (June 22-June 2, 2019), “We Suffer to Remain” (March 22-July 29) and “Lavar Munroe: Son of the Soil” (Sep. 13-Nov. 25), all of which have documented the traverse of Bahamian art from the picturesque to the uncompromising, unsentimental analysis and claiming of our unique multiplicity of selves, all of which deserve to be termed “Bahamian”, yet citizens of the world. This fortuitous positioning exposes how Bahamian artists have been among the leaders in negotiating the redefinition of Bahamian ethos and identity. Of prime importance, NAGB seems, with due caution to be inviting writers and historians from outside the institution to reflect on the process.

“Bushmen: Tale of Twin Gods”( 2012). Lavar Munroe. From the series ‘Grants Town Trickster” Mixed Media, 108″ x 46″ x 62”. Image courtesy of Lavar Munroe

Before the 1950s there was little art that could be justifiably termed “art of The Bahamas” in the sense of creation by native/resident Bahamians. A significant part of the National Collection from this era comprises primarily the works of transitory artists. Because their productions are mostly characterised by a sentimental, idealised outlook on nature, “Traversing the Picturesque” stimulated an abundance of critiques couched mainly in a sociopolitical idiom, focusing upon the art as a window on the dehumanising effects of colonialism in a post-slavery society. Many spoke of the works as falsifying indigenous history, heritages and value in the minds of their compatriots and subject peoples, thus distorting the worldview of the former and impeding beneficial self-definition of the latter.

Certainly, all art is political in some fashion and yes, ‘the conqueror’s story’ has often transmogrified non-European humanity—in good Bahamian—“Dey did useta ogly us up!” Consequently, there is justification in examining and positing a relationship between art from without and the identity dysphoria that peoples of the Black Atlantic and other post-colonial, African and Asian diasporic sites continue to suffer.

There is, however, a broader picture to be discerned. Here is a worldview shaped by relationships of inequity generations deep. While some artists may have been consciously racist, it would be missing out on a deeper fault line to believe all were so minded. More likely, their works were cast from generational metaphors conjured up for the sons and daughters of the “Old World”, whose amniotic fluid fed on the extractive imperialism of their forefathers. Their childhood porridge was likely sugared with tales of the divine right of Europe to the dominion of the entire planet, as well as the privateer heroism from Columbus to the modern foreign invest and how Europe saved the savages from barbarism.

Unfortunately, this deeply imbedded feeding tended to scarify mental and physical vision, reshaping landscapes and unique cultures. Artists coming from without were conditioned to see and render metaphors of lush Edens cultivated to feed their desires and pleasures. Where the main demographic was ethereal light and colour, the only accepted currency indolence and the only dynamic the ocean. We must consider whether the “tourist” artists were even physically endowed with receptors capable of perceiving the brutish reality of colonial life.

The gaze of the artist was simply not calibrated to see natives as any more than punctuation marks in the beautiful sentences of translucent seas and the vibrant colours dominating the tropical landscape. Experience limited to brief service contacts gave little opportunity for the concretization of, or even a desire to express the local people’s realities beyond cartoonish and caricature representation.

Strangely, it was the challenge to rescue the Bahamian economy from its age-old “boom and bust” treadmill that reinforced the faceless projection of Bahamian culture. The government of the day engaged a push for development tourism from the mid-19th century to a formidable drive to capitalise on the United States embargo against Cuba following the 1959 Castro-led revolution in that island. With the new Bahamas tourism promotion, Bahamian identity was to be intimately bound up with service the industry.

A Ministry of Tourism booklet noted:

As Bahamians, we must guard our heritage by providing the “best” service that we can so that we can greatly affect the return of repeat visitors…We must differentiate ourselves from the competition through the used (sic) of a “creative” tourism product, i.e., through the use of our people, i.e., attitudes, good service, great attractions, and a clean low crime environment. [2]

It would seem then that the “art of The Bahamas” was doomed to a Hades of eternal identity-denying night. Curiously, in the 1890s, the American painter Winslow Homer provided a harbinger of a brighter future in his “After the Hurricane” (1899). In this work, which stands out from the contemporaneous genre of exiled native humanity, the paradise myth is fractured. A forbidding sky and churning ocean form the backdrop for a real man, powerful muscles and face defined. He is obviously a victim of the hurricane; he is cast up on a beach, unconscious, his boat fractured. The question arises as to whether he will survive. This work and one of two others of Homer’s Bahamas period paintings show a greater definition, purpose, emotion, struggle and dynamism.

We turn now to the upwelling of truly indigenous art. Up to the 1950s, so-called “fine arts” were uncommon currency for Bahamians. Their milieu was circumscribed by a society where native creativity and impecunity limited Bahamian genius to the manipulation of wood and stone and the much-assailed Junkanoo masquerade tradition. Viewed as possessing the potential axis for organising rebellion, Junkanoo parades were twice prohibited by law. At best, like the “shouter chapels”, this composite of masquerade, music and unbridled dancing from our African heritage was regarded as a barbaric spectacle worthy only of providing amusement for visitors.

After the Hurricane (1899). Winslow Homer. Transparent watercolor, with touches of opaque watercolor, rewetting, blotting and scraping, over graphite, on moderately thick, moderately textured (twill texture on verso), ivory wove paper Inscriptions Signed recto, lower left corner, in brush and black watercolor. 380 x 543 mm. Image courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, sourced from the commons.

In this period, as in the age of slavery, identity, personal and national had to be carefully negotiated in stealthy movements—underground, camouflaged so to speak. Yet, Junkanoo artists’ very engagement with sponge, newsprint, raffia, straw and cardboard was a declaration of personhood and ability—a dynamic from within.

Then, a crack opened in a formerly tightly shut door. By mid-20th century, Junkanoo was undergoing conversion to tourist attraction, offered up as destination differentiation. The masquerade was sanitised and allowed to “stay up late”, like a child being given a holiday relaxation with strict instruction to “behave”. To survive economically and with dignity in the tourism dominated milieu, the Bahamian artist had to steer his craft carefully through the narrows of imperial governance and marketplace transaction, where sales depended heavily on leaving intact the gauzy veil of paradise. As Malcolm Andrews remarks, there is “something of the big-game hunter in these tourists, boasting of their encounters with savage landscapes, ‘capturing’ wild scenes, and ‘fixing’ them as pictorial trophies in order to sell them or hang them up in frames on their drawing room walls.” [3]

The late 1960s and the early 1970s prepared the maternity ward for the birthing not only of greater political freedom but also that of Bahamian art. One might say that the politics of the era—the advent of majority rule and independence produced substantial seeds for the generation of the latter. Adding significantly to this has been the contribution of greater access to tertiary education at home and abroad, more exposure to the wider world through television and travel.

It is noteworthy that the first large public art exhibition, curated by Olaf Froen opened in 1960. This event would be followed by other seminal developments that would thrust art into public consciousness as a worthy pursuit and not frowned upon as the Devil’s workshop for idle boys: RBC Summer Arts Workshop (1980), The Central Bank Art Competition (1984), Atlantis’ integration of Bahamian art throughout its complex (1990s/2000s) and, more recently, the University of The Bahamas’ Pro Gallery (2003) created “as an incubator space for the creative university community” and the establishment of The Current at Baha Mar (2017). It is essential to acknowledge the art publications—Bahamian Art 1492-1992 (Patricia Glinton, Charles Huggins & Basil Smith), Love & Responsibility (Dawn Davies/Erica James) and the exhibition catalogues of the NAGB, which are art pieces of themselves the growth of private art galleries—Doongalik Studios, D’Aguilar Art Foundation, Hillside House, Popop Studios, Ladder and the rise of dedicated collectors and benefactors such as Vincent D’Aguilar, Dawn Davies, other individuals, the Charitable Arts Foundation and several financial institutions. It would not be unreasonable to claim that this matrix produced much of the dynamism now perceived in the country’s visual arts.

This growing recognition for art helped to propel and elevate the output of such artists as the grand men of Bahamian art Maxwell Taylor, Eddie Minnis, brothers Stan and Jackson Burnside and Antonius Roberts, both progenitors and beneficiaries, who, inspired by the African renaissance in the United States, proclaimed a new national ethos. On Brent Malone’s canvases, the culture of The Bahamas and others from distant climes were melded into unity by the colours and rhythms of The Bahamas’ environment. Then there came John Beadle, Jolyon Smith, Clive Stuart, Erica James and Monique Rolle to name a few, who took the texts the great men offered—revised and extended the revolution with unapologetic pride.

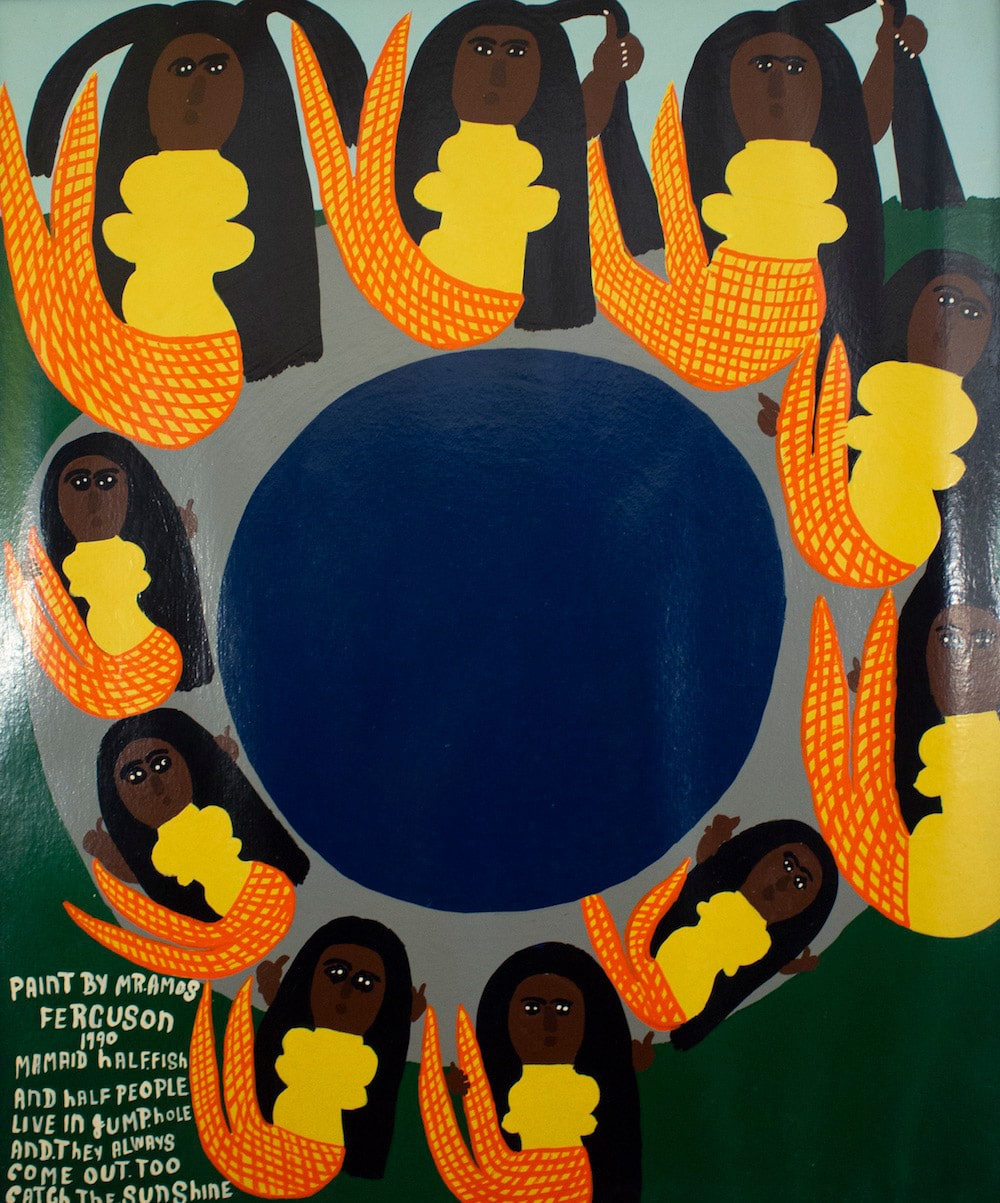

Great recognition must be accorded Kendal Hanna, who dared to be an abstractionist in the age of placid sailboats on the ocean. Equally, we owe tribute to Amos Ferguson, whose oeuvre dominates “Hard Mouth: From the Tongues of the Ocean”. Ferguson, termed “Bahamian outsider”, without formal education or training in the canons of art, demanded acceptance of and obeisance to his selfhood, to the queen of his life, Bea, his wife and to his unique vagaries of perspective and house paint on varied materials, sometimes salvage materials, which Ferguson ennobled in his work.

These and others of their generations were revolutionaries, a vanguard, who carried the standard for the creation of the vernacular of the art of The Bahamas, forged from the country’s history, heritage, its rhythms, blues and other primaries of the rich palette of the archipelago’s terrain and marine scape.

The 1990s and 2000s brought to the stage the Petit brothers, John Cox and others. These decades witnessed the greater incursion into the plastic and visual arts by women, such as Chantal Bethel, Jessica Colebrook, Dede Brown and the band of younger women artists fostered by the NAGB. It brought greater and necessary recognition to illustration and graphic/digital arts through the work of Dionne Benjamin and Neko Meicholas.

Revolution was Clive Stuart’s decades-ago installation on abortion and the enthroning of Black beauty on Stan Burnside’s canvases. Equally so is the way the brilliant John Beadle’s elevated corrugated cardboard into the telling vision of bondage rendered through his installation “Cuffed: held in check”. So too is Sonia Farmer’s book art and multi-performer reading titled “A True & Exact History”, both of which formed a signal part of “We Suffer to Remain”.

Then we come to Lavar Munroe’s retrospective “Son of the Soil”. We are simultaneously repelled and seduced by his collaging of the characteristic elements of the decaying Over-the-Hill Nassau community in which the artist grew up—the spray paint—the inner city art medium of choice, the bullet-riddled objects, the debris of “Witness”. Perhaps the star piece is the installation, which combines the vampiric, gold chain-laden evocation of the drug dealer, his life-ruining bags of the cursed white powder and his snarling dog, which underpin his ghetto kingship and embody the degradation of communities that produced many Bahamian geniuses like Munroe.

Munroe’s oeuvre has been lionised in many of the great art cities of the world, which is all the more extraordinary because this creative seems dedicated to fracturing Bahamian myths and freeing our closeted skeletons. Perhaps this success is born of his magisterial ability to distil nightmare and dysfunction, termed the “ugly” by the man himself, into undeniable beauty, provoking foundation-shaking thought.

“Mamaids. Half Fish Half People” (1990), Amos Ferguson, house paint on board, 36” x 30”. Image courtesy of the National Collection.

Most important of all the foregoing is the fearless willingness to rout placidity from the Bahamian artscape—to break dance across the forced and long acceptance of the myth of Christopher Columbus’ “discovery”, to dethrone “Rule Britannia”, to sanctify the washing of dirty social, political and economy laundry in public and to “be who we is and not who we ain’t” in the words of the late Jackson Burnside—in short, to further, of necessity, the revolution.

A fearful but diamond-in-the-raw opportunity has been granted The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas—the leading of this august cavalcade of Bahamian art, the uniqueness of which well advanced in ebulliently, laughing, ol’ storying and shoving its way into the consciousness of the jaded world of modern art. Unified, they will engender fresh revolution if able to resist the elitism and discrimination the international world hides beneath a constant outpouring of precious verbiage. Let’s reinstate the Aha! —the breathtaking moment as one of the criteria for judging great art. The artists themselves and the curators of the NAGB have already begun to cut the facets of a stone, which has already prismed enough light to show that it can emerge into a jewel of rare brilliance.

[1] Federico Fellini (1920–1993), Italian film director, in Atlantic Monthly, December 1965

[2] Delancy, Georgina. (1996) Tourism in the Islands of The Bahamas: Tourism Student Manual, Ministry of Tourism.

[3] Malcolm Andrews (1989): The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800, p. 67 Stanford: Stanford University Press