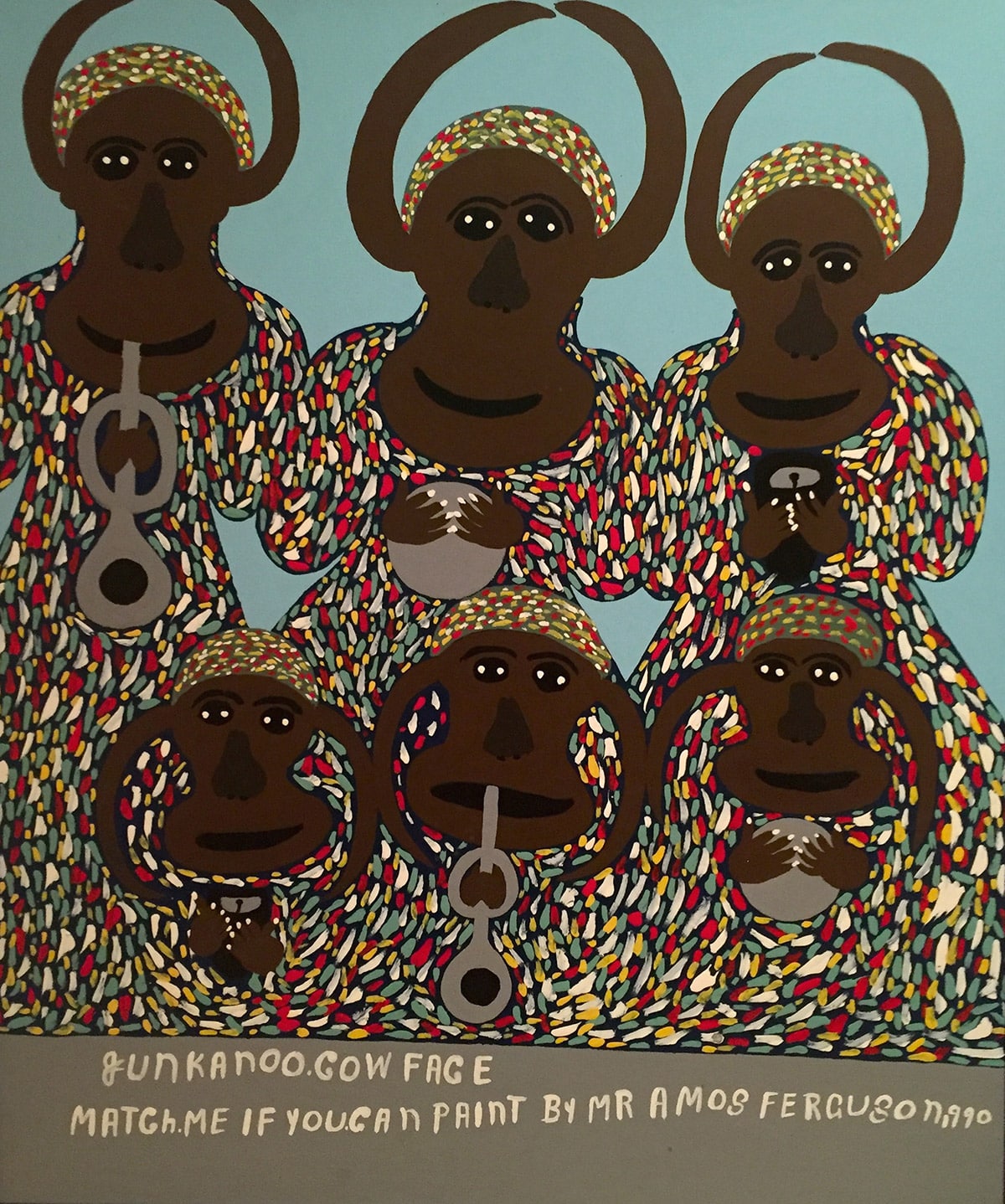

Amos Ferguson’s Junkanoo Cow Face: Match Me If You Can

The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas was an idea long before it was a reality. Many artworks, therefore, had been purchased and earmarked for the collection before its eventual incarnation in 2003. The Bahamian National Collection, now housed with us in the magnificently restored Villa Doyle, was originally founded on the purchase of 25 Amos Ferguson works.

Amos Ferguson, Junknaoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can, 1999. House paint on cardboard, 36 x 30 ins. National Collection.

The Honourable Perry Christie, our current Prime Minister, undertook the purchase when he was Minister of Tourism in 1992 at the behest of then-Prime Minister Sir Lynden Pindling and financed by the Central Bank of The Bahamas. The paintings were, for many years, housed at the Pompey Museum of Slavery and survived the 1992 fire in its historic location of Vendue House on Bay Street. Old film footage shows people rushing up and down the outside stairs, carrying Ferguson’s paintings, holding them dearly against their chests to rescue them from the conflagration. It is especially touching, to still have these masterpieces of Bahamian art in the NAGB collection.

This month’s selected artwork—Junkanoo Cow Face—was part of that original purchase and currently hangs in the Permanent Exhibition space on the ground floor (where the NAGB highlights pieces from the collection in thematic exhibitions), within a show entitled From Columbus to Junkanoo, curated by Jodi Minnis and Averia Wright. The exhibition speaks to various aspects of Bahamian evolution, society and culture, with Junkanoo as the crowning glory. Music was and still is an important aspect of Bahamian life, and it also played an important part in Ferguson’s life, both in the gospel he heard in Church and the spiritual music he listened to on his record player while he worked. In the ’50s, when Ferguson was a young man (he was born in 1920 in the Forest, Exuma), Nassau was already considered the hotspot for music and brought in a jet-set crowd.

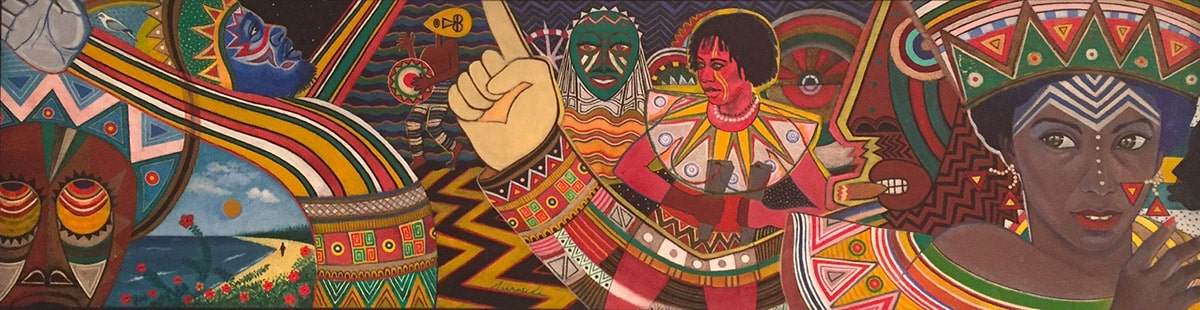

Stan Burnside, Spirits Rejoice, 1987. Oil on Canvas, 13 x 48 ins., D’Aguilar Art Collection.

In the ’60s, New Providence could boast of having over 60 nightclubs, including King and Knights, Peanut Taylor’s Drumbeat Club, The Big Bamboo, The Junkanoo Club, Chez Paul Meeres’ theater and nightclub and, of course the infamous Cat and Fiddle, a place that was also memorialized by Ferguson in an eponymous painting, currently in the D’Aguilar Foundation art collection. The Cat and Fiddle was run by Freddie Munnings Sr. and, in its heyday, saw such stellar artists as Sam Cooke, Frank Sinatra, James Brown, Aretha Franklin and Nat King Cole perform. Probably more important to most Bahamians, though, is indeed Junkanoo, involving multitudes of musician: drummers, bellers, whistlers, brass sections, and conch blowers; there are also dancers and, last but not least, the amazing costumes, such as illustrated in the current exhibition by works such as Stan Burnside’s 1987 “Spirits Rejoice” or Eric Ellis’ 1991 “Drum It Up”.

Nowadays, these are brightly-coloured, rhinestone-studded and feather-bedecked extravaganzas, which is why we might not immediately recognize the comparatively subdued costumes in the Ferguson painting, but traditionally they were made from refuse or discarded items—sponges, rags, torn newspaper—which later developed in the ’60s to cardboard and more colourful crêpe paper. Also very striking in Junkanoo Cow Face (and other junkanoo-themed works by Ferguson), are the barnyard animal faces, again not so usual to a modern-day audience that has come to expect multi-hued fishes or birds of paradise. Interestingly, this goes back to Junkanoo’s original roots as a West African celebration in which the masqueraders wore masks with large tusks on their heads, walked on tall stilts, and affixed cow tails to their backsides.

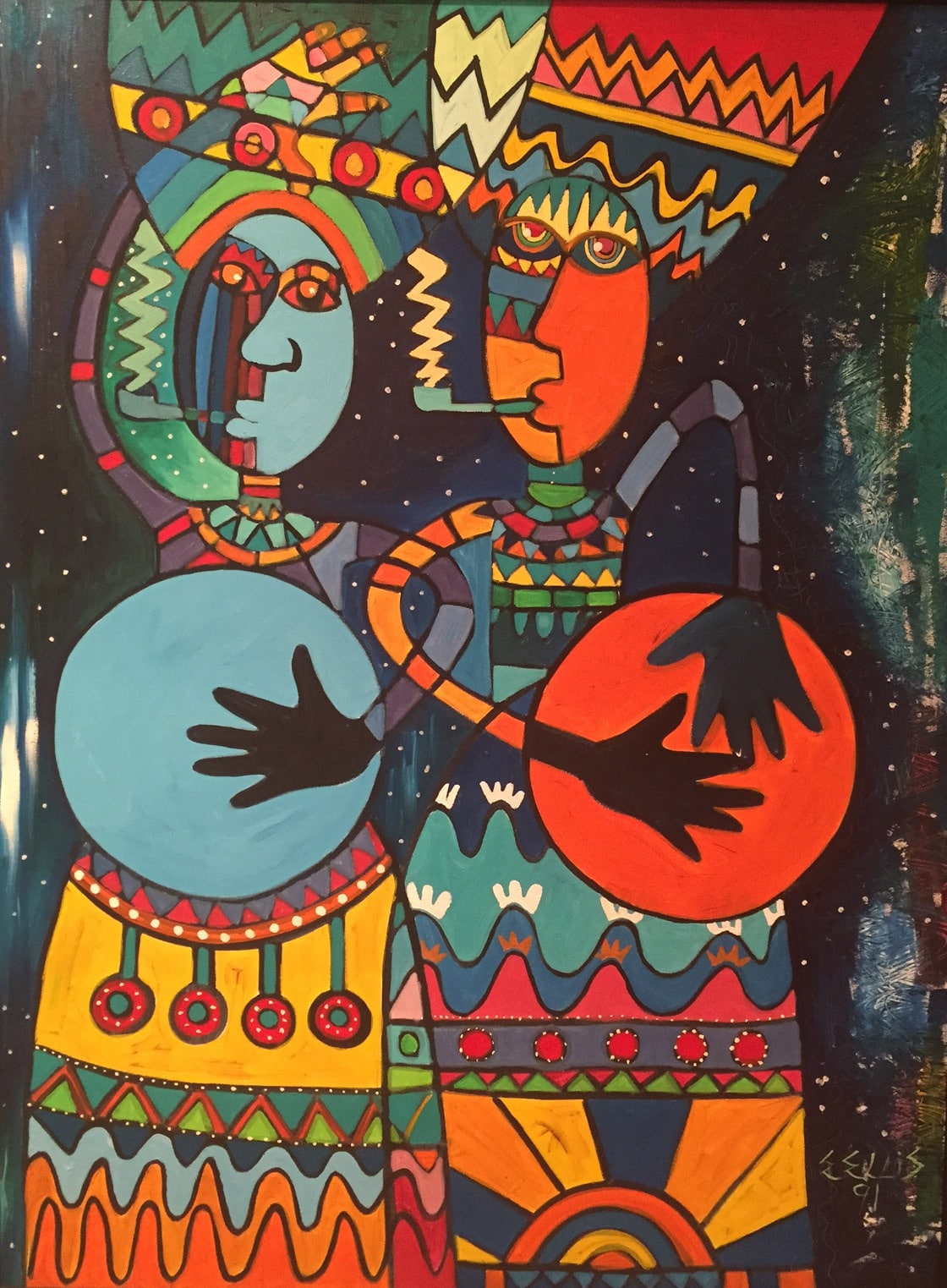

Eric Ellis, Drum It Up ,1991. Oil on Canvas, 42 x 32 ins., D’Aguilar Art Collection.

According to Herbert Been, Alfred Robinson and Herbert Ingham, regarding the similar ‘Massin’ festival in Turks & Caicos, the Cow Horn costume was usually worn by the Head Masquerader and, based on local folklore, represented the Devil. Along with a hideous mask, real cow’s horns were attached to a headdress and tied under the chin, a black jacket was donned and a tail called Reel-A-Tail, made of empty bobbin spools, completed the outfit.

While Ferguson continued to paint hundreds of Junkanoo images throughout his career, he admitted that he hadn’t been in a long time, so it could be many of the more old-fashioned costumes were painted from memories he had of Junkanoo costumes he’d seen as a young boy or could be simply works drawn from his imagination. As to whether he made some of the costumes up, he admitted, “I paints a picture of junkanoo more than any other artist said that they painting a picture of junkanoo. It’s a joke. Sometimes people see the junkanoo [painting] on the wall and ax me if I been to see junkanoo. ‘Cause I junkanoo myself.’ And you won’t find me no junkanoo and say, ‘Amos Ferguson, I can paint that. I don’t need to go’s to Bay Street or nobody comes into my mind.’ See what comes into my mind, I do do. In any form I can paints the junkanoo and get all the costume I want. It comes to me just like stars, every colours it comes to me like stars. Any junkanoo painting.”

Rolfe Harris, Junkanooer,1991. Oil on Canvas, 50 x 40 ins., D’Aguilar Art Collection.

Ferguson’s colourful language and Mohammad Ali-esque bravado is reflected in the painting’s inscription, which became his trademark phrase “Match me if You Can”! This was a challenge to all artists to paint as well as himself: the master. Ferguson was convinced of his brilliance even when people were mocking his technique—he used humble house paint and painted on cardboard—or made fun of his cartoon-like characters. Still today, many viewers will look at this naïve painting and say “What? I can do that!”. Early in his career and well into the 21st century, when his work become known worldwide, sceptics continue to shake their heads because his artwork is not “realistic.”

Take, for example, Rolfe Harris’ 1991 Junkanooer, also currently on view at the NAGB; now that—many would say—is great art! How does Ferguson match that? First of all, Ferguson’s technique was utterly unique. Painting with sticks, brushes and nails, he adorned everything around him, creating works on pizza boxes, Pringle boxes, glassware. Like many “Outsider” artists—that is, artists who often paint from visions, who are untrained and outside any constructed “system” of school or the market—he was urged to paint and, using very basic materials that were familiar to him from his former career as a house painter and furniture finisher. He painted the visions God sent him.

He painted the world, not as you and I see it, but as God revealed it to him. As simple as many of his works appear at first glance, his understanding of pattern, colour, form, and repetition, was very sophisticated with much of his later work looking not unlike fashionable fabric designs. Using household objects to paint is also not easy: during the retrospective exhibition at the NAGB in 2012, we covered an entire room in cardboard, left out house paint, brushes and nails, and encouraged visitors to “Paint Like Amos.” No-one could. His vision is unusual but unrepeatable and being a genuine original with a distinctive voice makes Amos Ferguson matchless and a tru-tru Bahamian icon.