By Natascha Vazquez

Lavar Munroe was born in 1982 in Nassau, The Bahamas, and currently lives and works in Maryland, USA. His works have been exhibited at the Venice Biennale, Italy; Nasher Museum of Art, USA; and the SCAD Museum of Art, USA. He graduated with a BFA from the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2007 and then earned an MA at Washington University in St. Louis. Alongside 5 other Bahamian artists, Munroe represented The Bahamas in the country’s first appearance at the Liverpool Biennale and has been awarded numerous prestigious prizes including a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painting and Sculpture Grant, a Fountainhead Residency and most recently a Post Doc Fellowship at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. In other words, Munroe is on the up and up, his star now brighter than it has ever been.

Munroe was born in Grants Town, one of the historic communities knows as the “Nation’s Navel” that has been neglected and fallen on hard times. Many of his works reflect the environment of his upbringing and his journey of survival and trauma in a world of gang violence, murder, drugs and self-discovery. Contrary to the loud and energetic visual language seen in Munroe’s work, he confronts the difficult relationships between authority and people of Over-the-Hill.

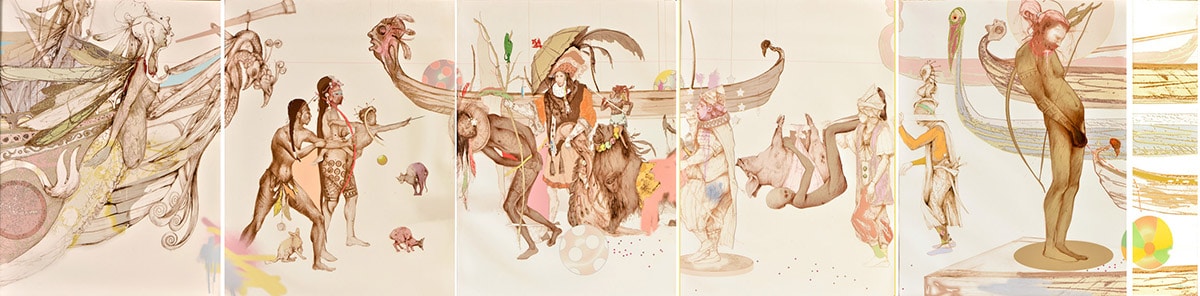

Lavar Munroe. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, 2011. Digital rendering. 34 x 25 (5), 34 x 10 (1). Image courtesy of The Dawn Davies Collection

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea (2011) portrays a digitally rendered work on six separate framed substrates. Although separated, the narrative of the piece continues throughout, depicting absurd scenery of indigenous people and colonialists interacting in a way that feels violent but playful at the same time. The paradox between these contrasting themes in the work creates a tension that adds layers of complexity to the work. Munroe works on a color palette that is at once dull, sparse and vibrant, creating a dynamism of play between forms. When one looks at the work, there are certain moments that recede, and others that rapidly capture the eye of the viewer. The colour choices bring wonder of the time period in which this work is defining – a period that occurred a long time ago, but also, with the use of vibrant colour and imagery, something that may still be going on today.

The first panel reveals the bow of a boat with a mermaid-like human quietly soaring besides, as if confronting a new land, moving towards it with force and confidence. There are subtle hints of blue and pink within the composition of mainly sepia colors, revealing a painterly quality to the drawn imagery. The mermaid/merman has multiple faces that are distorted, challenging the viewer’s interpretation of a specific identity. The forward facing individual and boat allow the eye to swiftly move from this panel to the next, with a desire to know more about where they might be looking, or perhaps, arriving.

The second panel portrays a scene where three indigenous people stand, one holding a baby and the other in a fighting position. He assertively holds a bow and arrow, pointing it as if he were in mid-shoot, aiming towards something that is still unknown to the viewer. The floor is scattered with three hairless cats, each wistfully positioned. They seem detatched from the rest of the composition, adding a layer of absurdity to the work. They theatrically wonder, gazing at the viewer, the floor and something hanging from the wardrobe of the fighting man. At the top right of the composition, the bow of another boat approaches, made up of a creature-like face staring into the distance in the opposite direction. There is a playful moment that interrupts – a shiny, colorful bouncy ball floats within the hull of the boat. The sheen and color of the ball contrasts the dramatic scenery given to us and we are distracted by a sense of play.

Detail of Lavar Munroe’s Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, 2011, part of the 2015 Permanent Exhibition, “From Columbus To Junkanoo”. Image courtesy of The Dawn Davies Collection.

The third panel seems the densest of all six, depicting a submissive indigenous man, bent over as if in pain in front of a colonially dressed man. He seems dominant, extensively dressed with traditional eighteenth century attire. A lion/hybrid-like creature follows him with a small servant man on his head, holding an umbrella over the colonialist. This gives more importance to this leading figure, as if he were of authority within this narrative. The motif of the ball is repeated again twice, once at the bottom of the composition and within the hull of the boat, again introducing a jocularity that contrasts the brutality of what is being portrayed between these beings. It seems suggestive of bearing light-heartedness and innocence to the cruelty associated with the colonization of indigenous land and people while also referencing the idea that the islands have long been seen and used as a “playground,” from first landfall to today.

The fourth panel exemplifies two colonial figures in mid-step, walking with a dead pig on a pole. The pig is tied up together with a naked indigenous man, both being carried out, almost as if they were simultaneously going to become a feast. The visual of both the pig and the man being carried together nods to the horrible treatment in which the indigenous, Lucayan people endured. They were not treated as fellow humans, but rather as tools to aid in the daily tasks of the foreigners, similar to their treatment of animals.

Munroe also draws inspiration from theories surrounding literature and mythology. He explores a number of social stereotypes in order to challenge discrepancies cutting across race, class, gender and age. According to the artist, “Though framed in fictional narratives, my work explores and in many ways critiques real life situations that I have either personally experienced or encountered through research. Often times, I am reminded of the underlying darkness that reoccurred in childhood fables – in a sense, drawing a parallel to the menacing motifs that occur in my work.”

Munroe’s cultural background plays a significant role in his creative process. Like many Bahamian artists, the origin of Munroe’s practice is in his uncle’s Junkanoo shack. According to Munroe, “My uncle is an artist. Not the type of artist I am – he does sign-making and before that he was a designer, and had a Junkanoo shack. So, growing up, I was always in that space. I looked up to him and I would watch him design and colour and cut paper and stuff. So it started that way, but from there I kind of grew on my own.”

Although shaped by background influences, he explains that his work seeks to evade expectations, “A lot of Caribbean and African-American artists, you expect them to do certain things. I expect to see many flowers in work coming from the Caribbean, I expect to see African-American artists painting something about slavery, or painting something with a black figure in it. Those things are very expected, and that’s something that I’ve always been anti: anti-expected.” Munroe delves into ideas of difference and the way it is mythologized. “We like to see difference. We are curious about difference and a lot of difference, until you see it, it’s like a myth.”

Detail of Lavar Munroe’s Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, 2011, part of the 2015 Permanent Exhibition, “From Columbus To Junkanoo”. Image courtesy of The Dawn Davies Collection.

The last two panels show a man urinating on a ball, exemplified by a dotted red line coming from his phallus. The repetition of the beach ball may refer to now-lost native ball game the Lucayan’s once played with the image reinforcing the disrespectful way in which the foreigners received the local people – their lives and culture – or could also suggest how a native population might feel about the “gift” of tourism.

Munroe uses his own visual language to depict the brutality of Columbus’ arrival into the islands. He dismisses the glorification of Columbus, and shows the horrific exploitation of enslaved natives of The Bahamas as well as Africans imported to the newly discovered land. In this piece, Columbus is the embodiment of the Devil. The subjugated native figures represent overturned humanity. Munroe uses bizarre imagery to depict the violent and destructive nature of uninvited change. Munroe strives to make the viewer re-think the admiration of Christopher Columbus and promote people’s desire to ward off any future threats of genocide and or “discovery.”