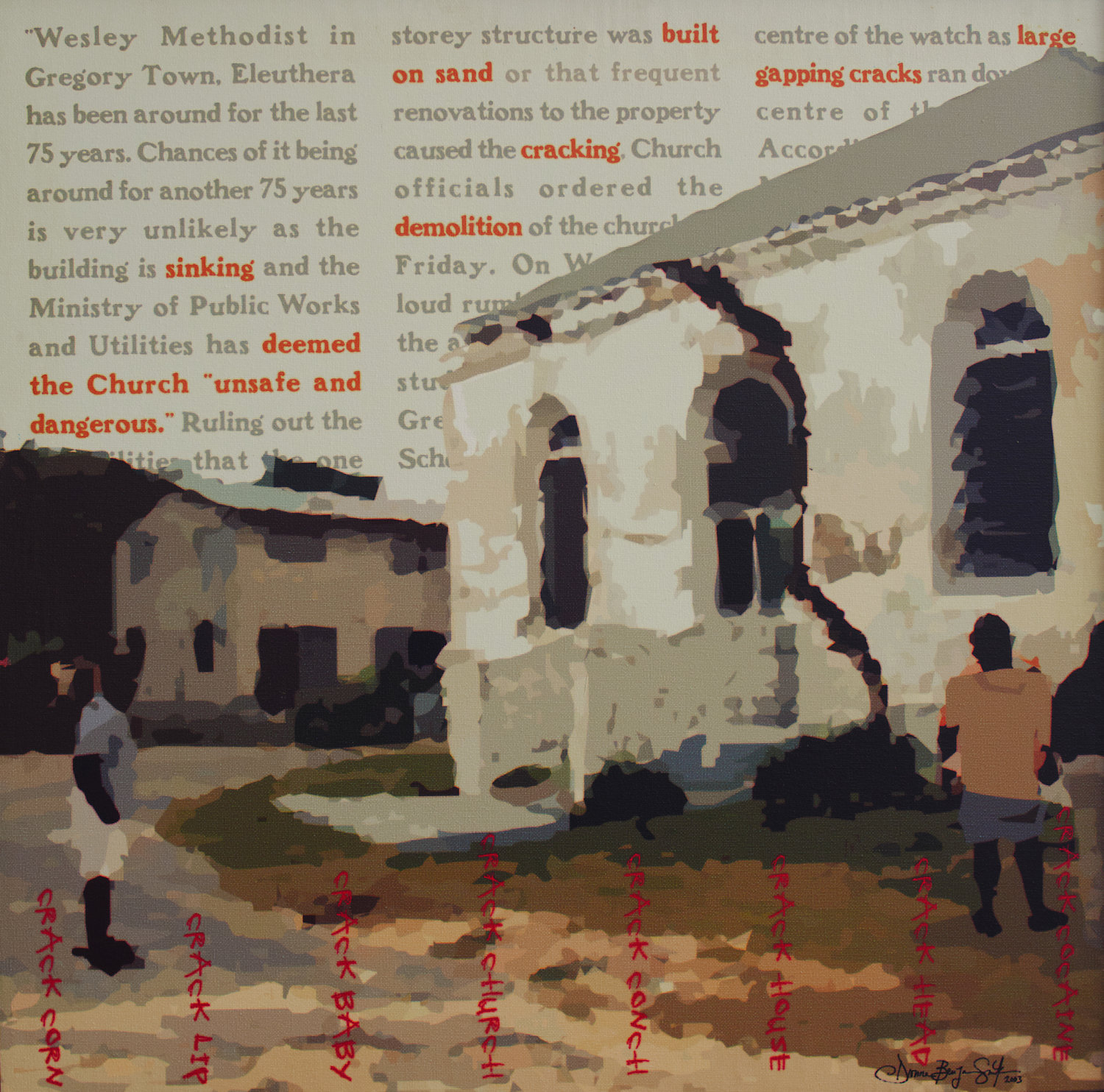

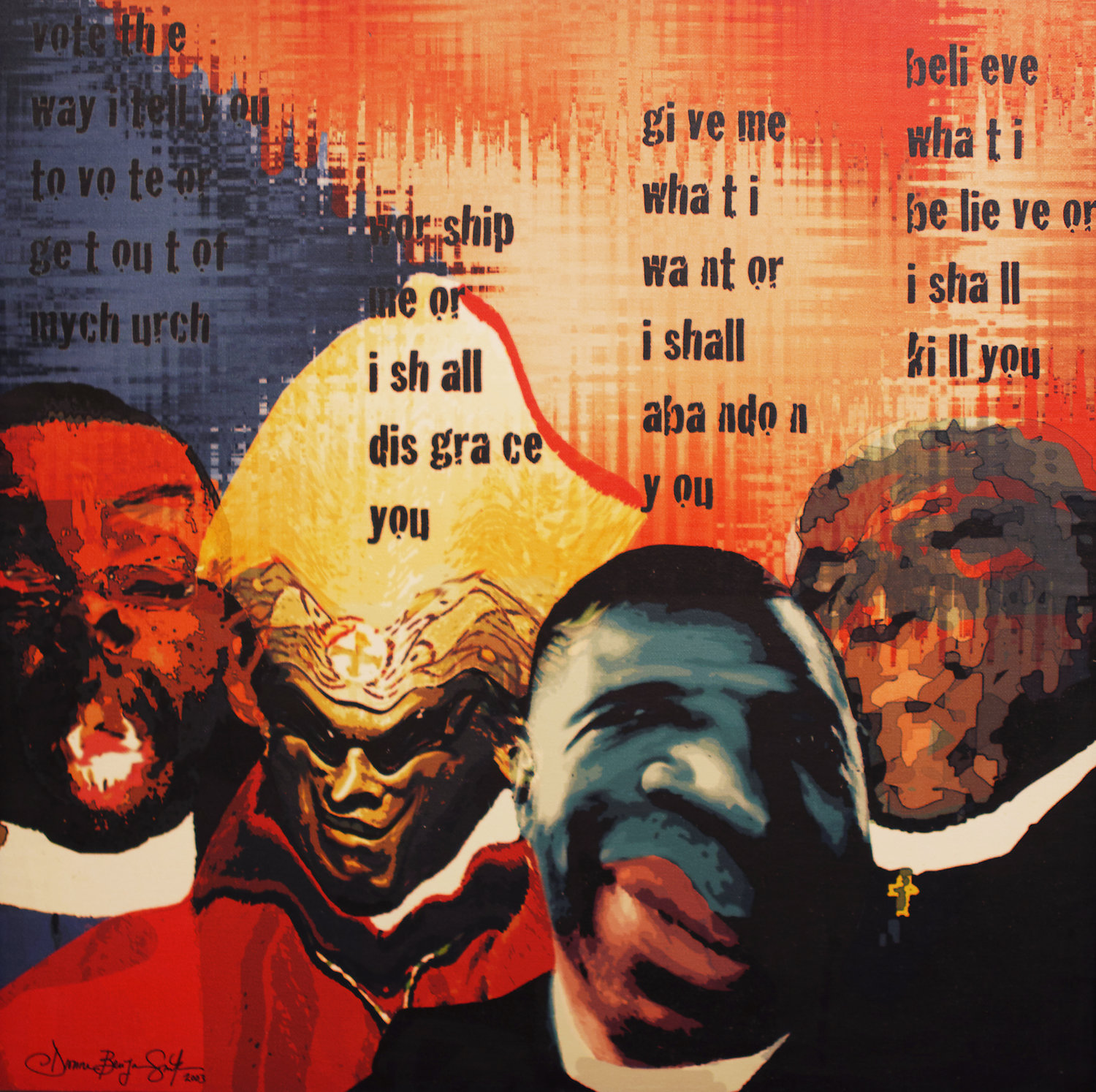

By Natalie Willis.“Built on Sand,” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith, is in some ways the sister work to “Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink,” (2003). Both works are of the same dimensions, which instantly makes us as viewers try to compare them and view them in the same plane when they are placed near each other, but, it is the critique and use of religion as their subject that makes them read like chapters in a book, feeding into each other and helping to inform a greater whole.

Currently browsing: Articles

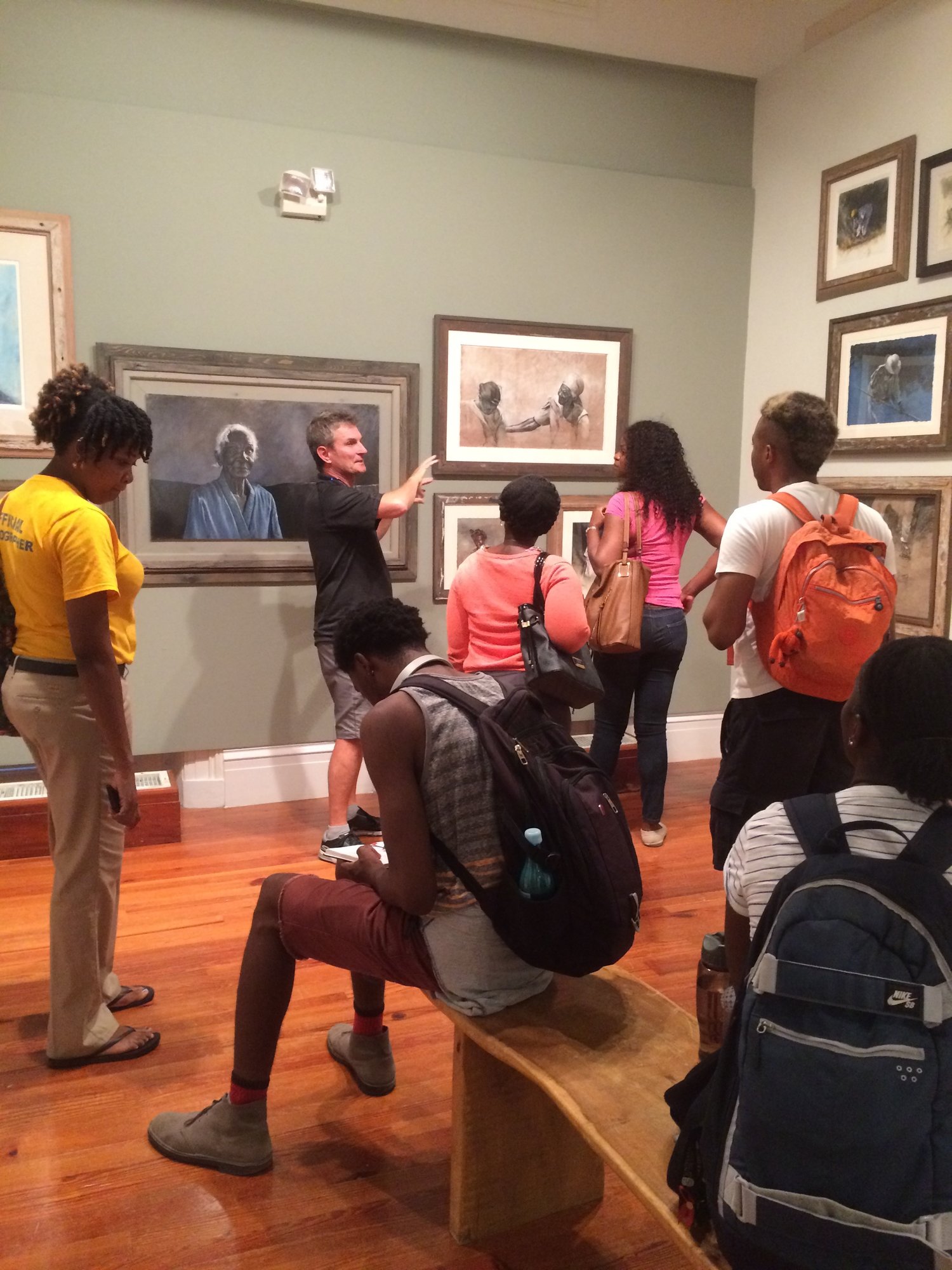

Art Documenting History: Intersecting complex histories with art

By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett. Art is a well-known document of history. All types of creative expression chronicle the moment they depict. Portraits, much like those on display in Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid are examples of this, especially the Goyas, for example. This column chooses to focus on the interlocking of art and history: “Art History,” its learning and teaching. So much happens in this somewhat fraught intersection between art and history, especially in a country like ours, where scant attention is paid to culture, except for its commodification and consumption.

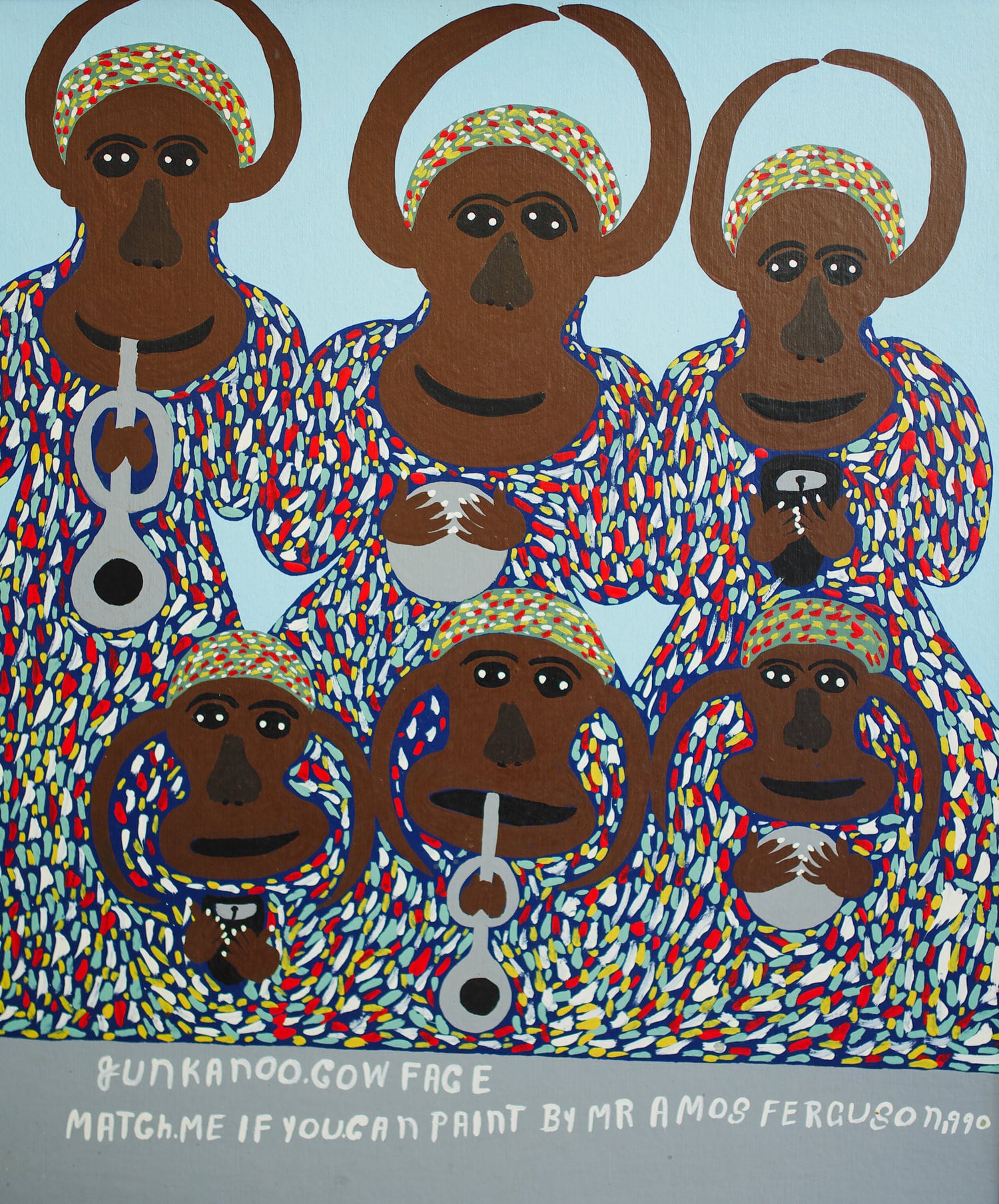

From The Collection: Amos Ferguson’s “Junkanoo Cow Face”

By Natascha Vazquez.

Bahamian artist and icon, Amos Ferguson radiantly portrays the spirit of Junkanoo through an energetic array of repeated imagery and texture in Junkanoo Cow Face – Match Me If You Can, an iconic piece in the Gallery’s National Collection. His interest in flattening the picture plane and depicting a graphic quality to the work is evident in this work, nodding to the style that he became widely known for. Ferguson used colour and repetition of form for impact and clarity. Arrangements of patterns flood his paintings, a visual language closely related to that of Bahamian culture, and in particular Junkanoo.

From the Collection: ‘Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink’ (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith

By Natalie Willis.Works dealing with the divine, with Christianity, with the spiritual, are very much rooted in what we consider to be part of our representation of Bahamianness. In looking to the work of Dionne Benjamin-Smith, an artist and graphic designer known for her pithy and no-holds-barred practice – and very informative and inclusive newsletter designed and created by herself and her partner – we can see a proudly proclaimed Bahamian woman who identifies with her Christianity taking acute aim at problems with the way we view religion in our country.

From the Collection: Lynn Parotti’s “The Blastocyst’s Ball: A Journey Through the Drug Induced stages of IVF”

By Natascha Vazques. Lynn Parotti is a Bahamian artist exploring themes of natural and biological landscape, those surrounding us and within us. In “The Blastocyst’s Ball,” Parotti displays a triptych of non-objective form and colour, alluding to something that may exist within biology or perhaps, more specifically, in our bodies. Each piece shows a unique arrangement but commonly shared hues and rigid texture created through repetition generate a strong sense of unity between them.

The Mark of a Woman: Portraits of Black Womanhood in the Work of Gabrielle Banks

By Natalie Willis. Reclining nudes, women posed ‘just so,’ we’re all quite accustomed to this kind of figuration and portraiture in the art world. Even those of us who are just dipping our toes into the wonders of the art world associate art with this kind of imagery. Art students at universities the world over can be found squinting in deepest concentration, poring over their depictions of a nude model before them – often a woman – and trying to figure out form, perspective, how to capture the ‘essence’ of this stranger they’ve met. It’s part of the canon, in many ways.

From the Collection: Michael Edwards’ “Untitled II”

By Natascha Vazquez. The interpretation of abstract art entails an inventiveness that allows you to discover for yourself the meaning behind the work. It’s an organic process, it has no equation or set of rules – the art presents itself and you are left with little information to process it. For many, this is unsettling. As humans, we yearn for understanding – we desire clear, detailed instruction. Abstract art provides none of that. Revolutionary colour field painter Mark Rothko says, “Art that truly engages us is felt even when you have turned your back on it.” There’s something really special about that – about feeling the sensation of a work beyond its physicality. It’s when you can feel the strength of the painting from across the room. You can stand in the space the artist once occupied and imagine him or her in that same spot, debating over the next smear of black or red pour or blue dot. Similarly, Jerry Saltz says, “Abstraction disenchants, re-enchants, detoxifies, destabilises, resists closure, slows perception, and increases our grasp of the world.”

Balancing Act: Heino Schmid’s Temporary Horizon (2010)

By Natalie Willis.Heino Schmid’s practice can perhaps be described as slippery or amphibious – and it’s not so much to do with the water, as it is to do with his fluidity in dealing with the bounds of what we believe to constitute drawing, sculpture, painting as separate genres – the proverbial lines in his practice become blurred. This movement between the medium and the means is why “Temporary Horizon” (2010) was chosen for the current Permanent Exhibition, “Revisiting An Eye For the Tropics” on display at the NAGB.

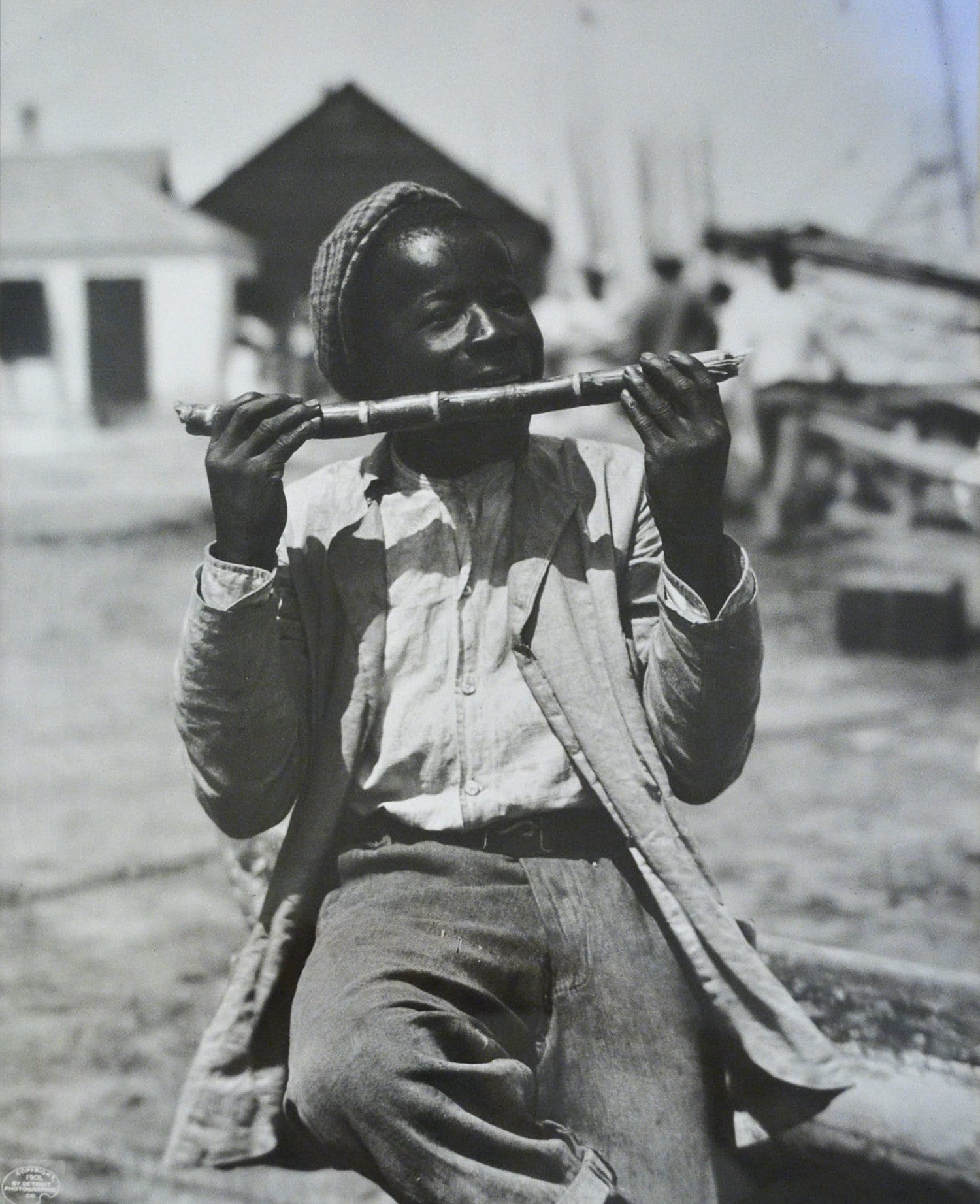

From The Collection: “A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) by William Henry Jackson

By Natalie Willis. “A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) by William Henry Jackson is part of the suite of historic colonial photographs in the National Collection. Jackson was an American, who started a photo studio here after emigrating from New York in the 1870s and is one of the small group of colonial migrants whose pictures help us piece together part of the story of the time. According to the catalogue for “Bahamian Visions: Photographs 1870 – 1920,” curated by Krista Thompson, Jackson first came to The Bahamas at the request of the Governor of the time, Sir William Robinson, in 1877. Since around 1856, Jackson worked as a landscape painter, colourist of photographs and also owned a studio specialising in Daguerreotype photographs. In addition, he manufactured albumenized paper, managed a stereoscopic printing shop and had even worked as a Civil War photographer. Many of these things seem very far removed from us now, but they were staples of photography at the time.

Cultural Development and Investment: The Recognition of Our Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage, shockingly, is actually not unique to or owned by a people unless it is inscribed as such. So, as a nation, we think we are the sole practitioners of Junkanoo the way we perform it on Boxing Day morning and New Year’s Day morning, however, this unique cultural relationship does not endow us, The Bahamas or the Bahamian people with the right to use Junkanoo as we wish. We do not own the practice nor do we benefit from it, despite the fact that whenever we are invited as a country to an arts or culture festival we tend to drag an entire Junkanoo group with us. The nation and the state have been historically irresponsible when it comes to officially claiming and so protecting our cultural heritage.