By Natascha Vazquez

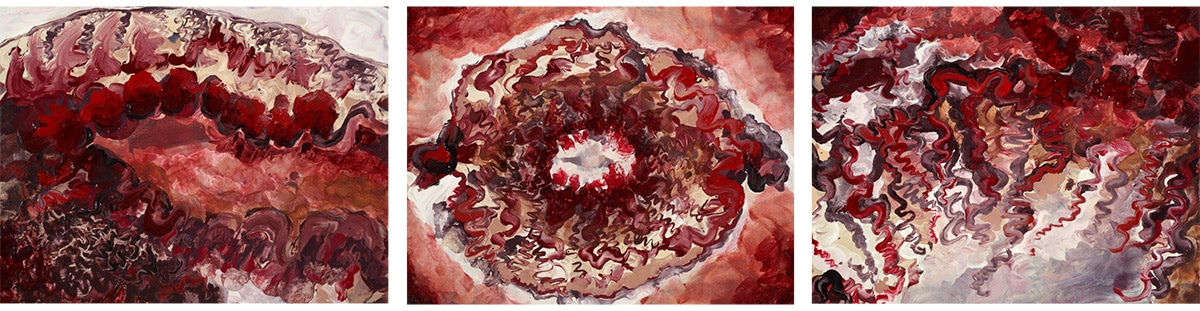

Lynn Parotti is a Bahamian artist exploring themes of natural and biological landscape, those surrounding us and within us. In “The Blastocyst’s Ball,” Parotti displays a triptych of non-objective form and colour, alluding to something that may exist within biology or perhaps, more specifically, in our bodies. Each piece shows a unique arrangement but commonly shared hues and rigid texture created through repetition generate a strong sense of unity between them.

Lynn Parotti’s ‘The Blastocyst’s Ball: A Journey Through the Drug Induced stages of IVF (IN VITRO FERTILISATION) Featuring Ovitrelle’s Luteal Lune, Crinone’s Crave, & Follistimitus Irreconcilibus’ (2008), oil on canvas, 13 x 17 (3). Part of the National Collection.

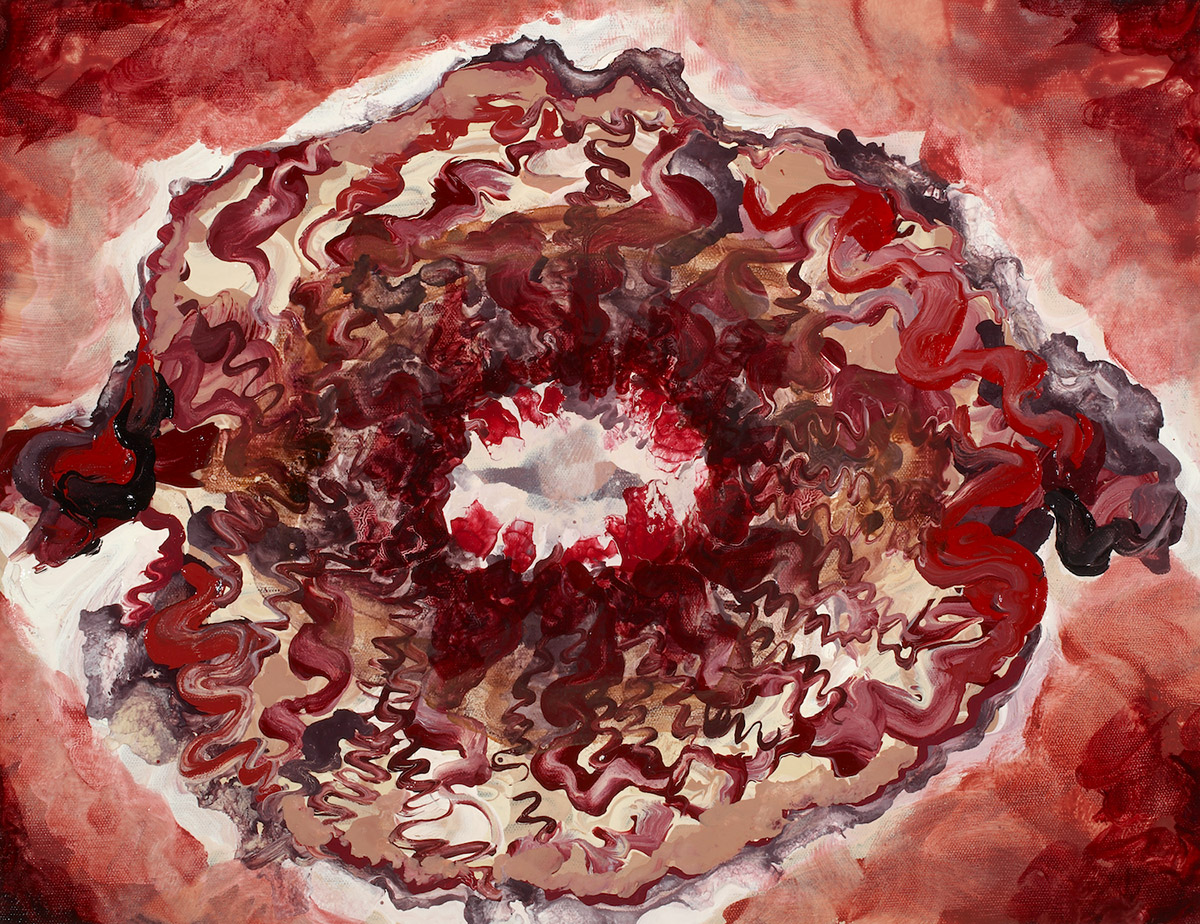

Organic form in reds, whites, purples and browns occupy each composition. Some forms are stacked, building up masses that blend each curvilinear line into a whole. Others sit next to one another, actively, dispersing into space to reveal their individuality. The last panel exhibits similar forms wrapping around to create a single circular shape, an opening of some sort, and the uniqueness of each mark disappears again.

Parotti portrays a plethora of organic form and line, specifically those of a circle. In the first piece, the repetition of curved lines creates an imperfect circular shape. Circles have neither beginning nor end, and for that, they often represent the eternal whole. They are used to suggest familiar objects by relating to our natural surroundings, as well as to our bodies. To some, their curves are seen as feminine.

Lynn Parotti’s ‘The Blastocyst’s Ball: Ovitrelle’s Luteal Lune’ (2008), oil on canvas, 13 x 17 (3). Part of the National Collection.

There are no concrete rules about what colours are exclusively feminine or masculine, but there have been studies over the past decades that draw some generalisations. A study, executed in 2003 by Joe Hallock, compared colour preferences among various demographics. He surveyed 232 people amongst 22 different countries around the world. The study showed that women preferred colours that are closer to the red end of the spectrum. For that reason, we tend to associate reds with femininity. Parotti’s consideration of warm hues not only acts as a reference to the body but also implies a further indication to specifically female biology.

Red is the hottest all of primary colours, making it highly stimulating for the viewer’s eye. It is a colour that tends to stir up passion, both in a negative and positive light. Being the colour of blood and fire, it may be associated with meanings of love, passion, desire, heat, longing, lust, sexuality and energy, to name a few. It is an emotionally intense colour that is said to enhance human metabolism, increase respiration rate and raise blood pressure. The effect this hue has on our bodies directly correlates with the subject matter that Parotti presents, adding a dynamic layer of context to the work, and to the experience between the viewer and the art.

Lynn Parotti’s ‘The Blastocyst’s Ball: Crinone’s Crave’ (2008), oil on canvas, 13 x 17 (3). Part of the National Collection.

Besides formal interpretations of the piece, the title provided by Parotti is a direct insight into the content of the works. They abstractly portray the process of assisted reproduction, or in-vitro fertilisation (IVF), in which several eggs are removed form the ovaries, externally fertilised and then—as embryos—are returned into the uterus in the hope that they implant and become a pregnancy.

. Woman having IVF are given special reproductive hormones to encourage several eggs to develop in the ovaries. Final maturation of the egg itself is induced by the administration of a further hormone. 36 hours later, the fluid containing the eggs is drawn from the ovary with a needle, this is usually performed under light sedation with a doctor using ultrasound to check proceedings. The eggs collected from the ovary are then mixed with a sample of the male partner sperm, which has already been washed and concentrated.

Lynn Parotti’s ‘The Blastocyst’s Ball: Follistimitus Irreconcilibus’ (2008), oil on canvas, 13 x 17 (3). Part of the National Collection.

The eggs and sperm are left in an incubator set at 37 degrees for 24 hours so that fertilisation can take place. During this time, only one of the many sperm cells will penetrate the outer layer of the egg and achieve fertilisation. Following fertilisation, the cells divide and multiply and form an embryo. After 2 or 3 days, a healthy embryo will comprise around eight cells. It is then transferred to the uterus using a thin, flexible tube where it is left to implant and form a pregnancy.

Although IVF is a helpful tool for infertile couples, there is some controversy with the misuse of this technology. Aldous Huxley suggested that “test tube baby” technology wasn’t actually about infertility, it was about eugenics. Eugenics is a set of beliefs that aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population. IVF was about making super-babies: better babies, stronger babies, smarter babies, with an aim to make the perfect baby. Rather than it being of interest between infertile couples, it would be of interest to government and authoritarian states. Why would we allow any ordinary people to fall in love and have babies? There is less control that way. Could we control the process in a test tube and select specific traits in children that would be useful for society? The concern of this technology is in its misuse. Through IVF, are we going to breed ourselves to improve ourselves?