By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett

Edwidge Danticat’s book of essays Create Dangerously lead essay tells the story of François Duvalier, Papa Doc, bringing all the school children and the working community out to see the hanging of two young men. It was to set the example of what would happen to artists who chose to create dangerously. The idea behind the action of the public killings was that the public would not challenge the authority of the state. Instead, the population chose to tell stories that resisted the power of the dictator; they chose to create dangerously. Art is a vehicle for community expression and resilience.

John Beadle. Row Yah Boat. Sculptural Installation for NE8

The Haitian people are resourceful and resilient in the face of decades of tyranny and dictatorship. Can we learn from them? Have we learned from them? The Bahamas has apparently, never experienced such tyranny or dictatorship, but Danticat’s work needs to be understood in the current context. There was apparently no need for dictatorship when other means were used to maintain the status quo. As a democracy, one does not want to create waves, especially when we live below sea level, for many, and barely above sea level for some.

What has helped is that The Bahamas is not known for its novels nor its books – this is thankfully changing,– it is however known for having a high GDP, that if we create dangerously could be taken from us. This ‘threat’ of losing economic ground and becoming like Haiti is a cultural fact that can be traced back generations. Bahamian Culture was created to distrust, avoid and hate Haitian culture and the reality that is Haiti.

We accepted that culture of fear and distrust, and according to that culture, Haitians are rough and violent people, something that one would hear often growing up. They are also harbingers of doom. ‘Look at Haiti’ as if to say that they caused it all. Our lesson was always if we chose to create dangerously, we would end up like that. Our culture was moulded as a reaction to threats, as Nicolette Bethel asserts. Moreover, fear was sown into souls so that they did not hold forth; they did not challenge, and the only challenge would ever be the Mace and the Hourglass being thrown from Parliament. The General Strike, if we listen to the current folks, did not happen, except when it is convenient for them to use it.

Bahamian history is usually cleansed of all resistance to bad treatment and exploitation. We now wrap our stories in bacon and fry them up so that no one knows what they are eating. Much like the ‘sacking,’ covering in sackcloth, of tree trunks for Christmas. We have become a safe place where invaders are welcomed and shown where safes and lockboxes are, and, in some instances, they are given the keys to the country without so much as a question asked. We shall not speak out. Our culture is gratitude and silence-tourism! Art and culture often collide with this idea of docility.

In Danticat’s essay, she uses Albert Camus’ play Caligula to create a parallel with the Haitian history of torture and exploitation, but also their resilience.

“They needed to be convinced that words could still be spoken, that stories could still be told and passed on. So, as my father used to tell it, these young people donned white sheets as togas and they tried to stage Camus’ play—quietly, quietly—in many of their houses, where they whispered lines like:

Execution relieves and liberates. It is a universal tonic, just in precept as in practice. A man dies because he is guilty. A man is guilty because he is one of Caligula’s subjects. Ergo all men are guilty and shall die. It is only a matter of time and patience. The legend of the underground staging of this and other plays, clandestine readings of pieces of literature, was so strong that years after Papa Doc Duvalier died, every time there was a political murder in Bel Air, one of the young aspiring intellectuals in the neighborhood where I spent the first twelve years of my life might inevitably say that someone should put on a play.”

Susan Katz-Lightbourn. Remember. Mixed Media Installation. NE8

As the need to speak out deepens, to use words that we have been told are treacherous, are not respectful of those in power, we are taught that we should be submissive, subservient, smiling folks who love tourism. We shall do nothing that would upset that Trojan horse because it is as much as the sacred calf. Han’ come, han’ go, we shall always be quiet.

Our stories are lost in the vats of bootlegged rum that brought riches to some, under the guise of beds rolled down on evenings where tourists lay to enjoy the sounds of Yellow Bird, cooing outside. Bahamian culture is not silent, but being corralled into a waiting pen as if for slaughter.

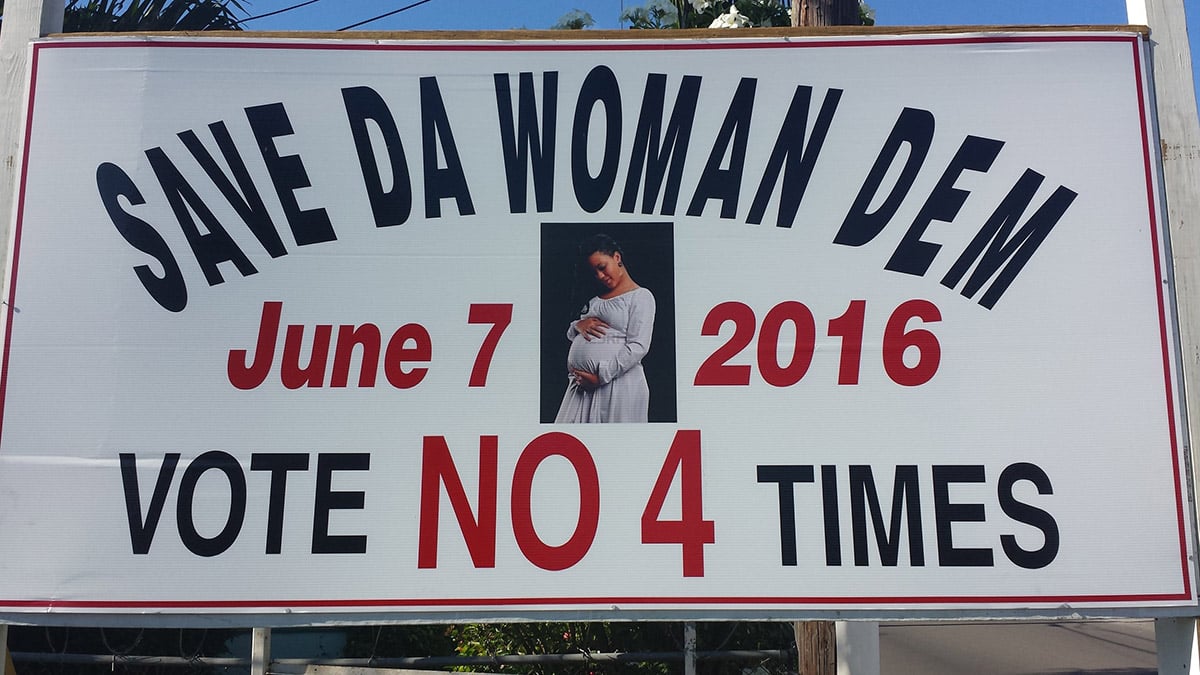

The stories, placards, posters, banners walked silently up Bay Street speak volumes of no surrender, even when we are told that are tongues shall be tamed, our feet held to a fire that should have been extinguished with slavery, but never died because it benefitted too many. We are threatened not with the gouging out of eyes, but with unemployment.

We shall not question the master in the great house who looks after and protects us from all evil, even when, as Juan Luis Guerra sings, the cost of living rises beyond our pocket’s ability. Bahamian stories are alive in Bahamian art, less visible in Bahamian novels, (because there are fewer), but thriving in mouth to ear, where the vernacular lives and cakes of resistance, pies ‘of peace and do not mess with me today’.

When dead people voted, ghosts haunted trees teaming with amulets to ward off evil doers. When dead people voted, the party line rang, and Batelco listened. As BEC become BPL and rates rise to pay for Machew, we know that we live in silence, except when ‘you mash my toe, and I cuss you.’ Remember massa in de big house safe behind de gates (behin de gates did use to mean one ting, but now it mean all kind a ting).

Edwidge Danticat’s ‘Create Dangerously’ speaks to our ability to fashion language out of tongues tamed by tying under colonial language vanquished. Our culture is not for sale, though, even though our tongues may be tied by unemployment and dried by thirst, thickened by the weight of dead people voting. In Duvalier’s Haiti violence did not kill spirits. The public execution of two young men did not destroy Haitian culture, as planned, it did not subdue an untamed soul.

Holly Parotti. i am not a witness. Installation. Part of the work for the National Exhibition 8.

Danticat notes: “The artists who came up with these other types of memorial art, the art that could replace the dead bodies, may also have wanted to save lives. In the face of both external and internal destruction, we are still trying to create as dangerously as they, as though each piece of art were a stand in for life, a soul, a future”.

We are all artists, especially when life sells us to silence and tells us that it is the voice. When we are taught to cow down to massa after mass day done, when we are made to understand that we are less than in our land, when we are told that when we protest our lack of access, we are ungrateful. How is being ungrateful e linked to silent acceptance when the tools used to liberate us are the very tools we are now told shall never be used again? Indeed, we cannot ever use those tools again; their day is done.

They will be surveilled as much as the prison. Gratitude is a dangerous, deadly weapon, especially when it is used to control.

Danticat states: “When our worlds are crumbling, we tell ourselves how right they may have been, our elders, about our passive careers as distant witnesses.”

But far too much is at stake for passive careers as those we have known for decades, before emancipation, before independence and after majority claim, they took over the rule, silence has blanketed us. “Who do we think we are?” asks Danticat in her essay. We think we are Bahamian artists, singers, storytellers, sculptors, cooks, gardeners, farmers, tailors whose stories may be at the bottom of bootleg barrels of rum, but are resoundingly alive even after the Burma Road Riots were said to have made it all right now, and we were told that to wear black and protest our exploitation quietly was an act of anti-nationalism, ingratitude for all the great house has done to liberate us from eternal damnation.

Voices rose quietly, without the din of guns, without the death of anyone except the generations who have died so that we can live. Our culture is not the aesthetics of trees wrapped in burlap to look like breasts or blunt penises. Our culture is not silent, though it seems dulled into relative submission.

Our culture, as long as we wish it to be, is alive in those feet that pound the streets because they do not have cars, in the rubber that heads north every morning and south every night to earn money to survive. The fear of suffering is as strong as the possibility of death by silence, though silence kills like cancer that eats away at our fibre and when we are asked, who do we think we are? What dare we answer?