‘Clay Oven’ seems to be a quiet watercolour, content to sit amongst the bright splashes of colour from John Beadle, Jackson Burnside or Brent Malone. If you were unfortunate enough to have a flying visit to see ‘From Columbus To Junkanoo’, where you had a supermarket dash style run through the galleries then you might miss it. But this kind of work can be the most interesting, especially if one has the time to scour, to be curious and stroll. Sometimes the things that don’t have the flash and bang and spectacle we love so much in Caribbean work; things that don’t have the unabashedly bright colours and bold strokes and jarring geometric shapes, provides us a moment where we can pause to think, make connections and ask something of the quietude presented.

‘Clay Oven’ (1912) is earthy, it is full of sepias and greens and stony grays, and, it is homely and sincere. This watercolour by ex-patriot Elmer Joseph Read, more commonly known as E. J. Read, is of our oldest works in the National Collection, outside of the traditional black and white film photography by Jacob Coonley, on display in the first wing of the current Permanent Exhibition ‘From Columbus to Junkanoo’ curated by Averia Wright and Jodi Minnis. While the photography of ‘Doc’ Sands and Jacob Coonley are immensely important to us in seeing what our colonial Bahamas of the 18th Century looked like, Read’s work is significant in a similar way.

‘Clay Oven’ (1912), E.J. Read, 14” x 19”, watercolour on paper. Part of the National Collection as seen in the Permanent Exhibition.

‘Clay Oven’ is a picture of domestic life and work, and the loose strokes and lack of detail in the faces makes us feel that these people could be any of our ancestors. The hearth in classical paintings was often used as a way to show people in conversation, in their domestic spaces – and here too it is domestic, but it is tending to the flame of sustenance and life rather than conversation. Living off the land takes work, and this image makes it seem quite quaint – but it was commonplace, it was how people lived. Perhaps if the image were to be reimagined now, the bodies toiling away in the sun and in front of the fire would be covered in the sweat of their hard work, their eyes would be squinting against the light and the heat of their struggle – rather than the romantic notion of unblemished pale blue or yellow clothing.

‘Clay Oven’ is not a portrait of realism but one of an idea of a place. The figures present are more than likely not people asked to sit for long periods of time, posing, and therefore not at all like the people with the stern faces we see in so many portraits and photographs from that time. These are working women going about their daily toil, and young ones occupying themselves with anything to hand. The palette suggests a quaint scene, but the way these women are working is anything but tranquil. This is hard graft. They aren’t being depicted for likeness perhaps so much as they are for feeling – which is apparent in the small child staring blankly at the viewer as he catches a ride in the cart of slightly older youth. This is a moment of people going about their daily business; there is nothing out of the ordinary for those depicted. In fact, the mothers-cum-cooks-cum-farmers and their children could be representative of the idea of a number of people in similar situations. It seems that it is honest and sincere, but in truth, it is problematic.

While the photographs of Coonley contain some of our first visual documentation of Bahamians of that era, this painting does so as well. But where the former is capturing a moment with a certain sense of immediacy – because despite the time it took for film to record an image – photographs were still considerably faster to produce than a painting of this nature. Though both were expensive; the latter tries to interpret these moments in a marginally different manner, to give feeling where many of the photographs simply logistically could not.

Furthermore, both this watercolour and the colonial photography provide us with the representation of everyday Bahamians that we so desperately need in helping us to anchor where we come from. Seeing black bodies in photographs and paintings from this period aids us in seeing and re-writing our stories into history now with the various strides being made in art history and cultural studies alike. Taking the time to re-inscribe ourselves helps us to feel like we can do at least a little of the talking instead of being talked about. So this is the significance of historical imagery and scholarship for us today, to reinscribe ourselves and our importance and struggles into stories that might have skewed them because of who was doing the photo-taking and who was doing the painting. We are all subject to our subjectivities, no matter what level of privilege or lack thereof – the key is to be open about them.

While both visuals give us depictions of black bodies in these spaces when ordinarily they mightn’t have been photographed or painted had they been anywhere else, it is still an idealised and romanticised depiction of the ‘native.’ The trope of the ‘happy local’ toiling away is ubiquitous in images from this period. So while we are happy to have representation and images present at all, what is the cost at which this is done?

Elmer Joseph Read was simply a privileged observer of his time. American-born and with means, like many of our colonial photographers in the collection, he came to Nassau with a very specific viewpoint in life. He lived during a time with an obvious divide in power, class, and race – but yet, he still saw fit to take the time to show everyday Bahamian life, to render it in his way. The act of choosing to paint can be political in itself because of the time and effort it takes as much as the intentions the painter wishes to share. In choosing to spend the time to render this image of Bahamian women working, doing manual labour no less in a time when many of the women that Read would know personally could never be seen to get their hands dirty, is a political act. He chose to depict these women and children though the image would be so commonplace – in short, he chose to see and to spend the time painting them acts as a choice decision in where to invest his time when it could be spent elsewhere. The act of depicting the everyday serves as a way to bring it into sharper focus, to allow for time to be spent giving these things more than a cursory glance, to allow us not to take them for granted.

Watercolours are so often associated with leisure and the gentry, but now we do of course have more recent artists reclaiming the medium from this elitist tradition. All of the work being done is ‘on the shoulders of giants’ as they say. We live in an era where we know more about hegemony and power struggles and have the capacity to fight it. Having these glimpses into the past helps us to stand taller when we see where we are now, no matter how unsettled and troubling the times are at present.

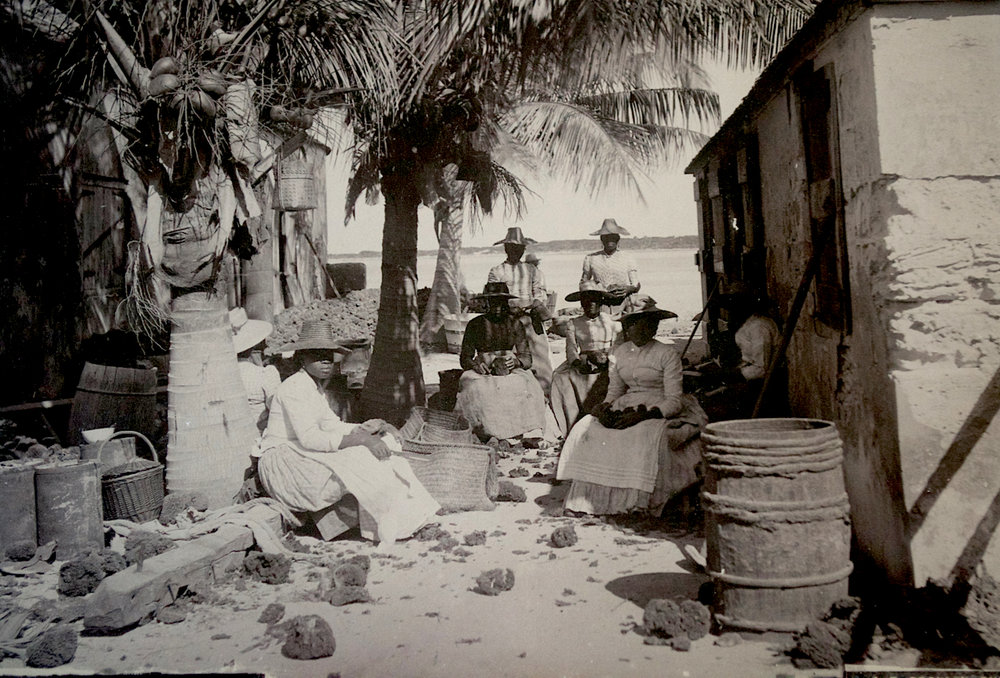

‘A Sponge Yard, Trimming’ ca. 1870, Albumen print, Jacob F. Coonley.

And the present is where we are now, and we can find a bit of the present here within the subtle landscape, within the countryside bathed in swashes of greens and browns and a great swathe of blue washing across a clear sky. And this is very familiar in its own way. Bahamians are seen as living happy lives of servitude that is all too ingrained to us, the idea of always being in service of! But we are now choosing to challenge this notion, some of us are choosing to change the nature our tourism to serve ourselves just a little, rather than to sycophantically seek to please others; some are learning to trust in our beauty and richness rather than trying to fit ourselves to an image that lacks truth and integrity. We are working to reify ourselves outside of a falsified image we have taken as truth, and the work most recently showcased in the National Exhibition 8 (NE8) shows the efforts being made to be critical of our identities outside of this tourist branding, to be honest with ourselves.

Jodi Minnis. Stills from The Gaulin, She Went to the Water performance, 2016. Works presented as part of the National Exhibition 8. Images courtesy of Jodi Minnis.

Amidst the work dealing with these aftershocks of the colonial era that continue to keep us on shaky ground and tenuous ties to knowing ourselves, we have the work of Jodi Minnis. Minnis’ work, ‘The Gualin: She Went to the Water’ in its political statement, exists as a one-time unique performance. There are of course images to document the event, but the fact that it exists as a moment, that it deals with black womanhood, that it deals with labour (perhaps in both senses), that it deals with baptism and rebirth – and the fact that it took place on the grounds of Villa Doyle, this reclaimed post-colonial building, shows a concerted effort to exert our energies into working for ourselves for a change.

As we come to the end of the year, we can look to the hearth of Read’s depiction, to the lazy spiral of smoke emerging from it, as a way to temper ourselves for newly imagined futures. We have dug up and instigated much this year that is not ideal, and it shows, but sometimes you have to uproot what you know to till the ground for something new – and hopefully we can take this chance to plant seeds of something fruitful for a new year.