By Natalie Willis.

Rembrandt Taylor is truly a master of his craft. His meticulous attention to lines and cell-shaded blocks of colour is testament to his skill. His body of artwork generally contain references to Exodus, to Black kings and queens, to religion, and his beliefs as Rastafari are clear and given deference. The religious and social movement, which began in the 1930s in Jamaica, gives rich territory for explorations of faith and identity, of self, and Taylor doesn’t shy away from re-framing the conversation to suit his roots.

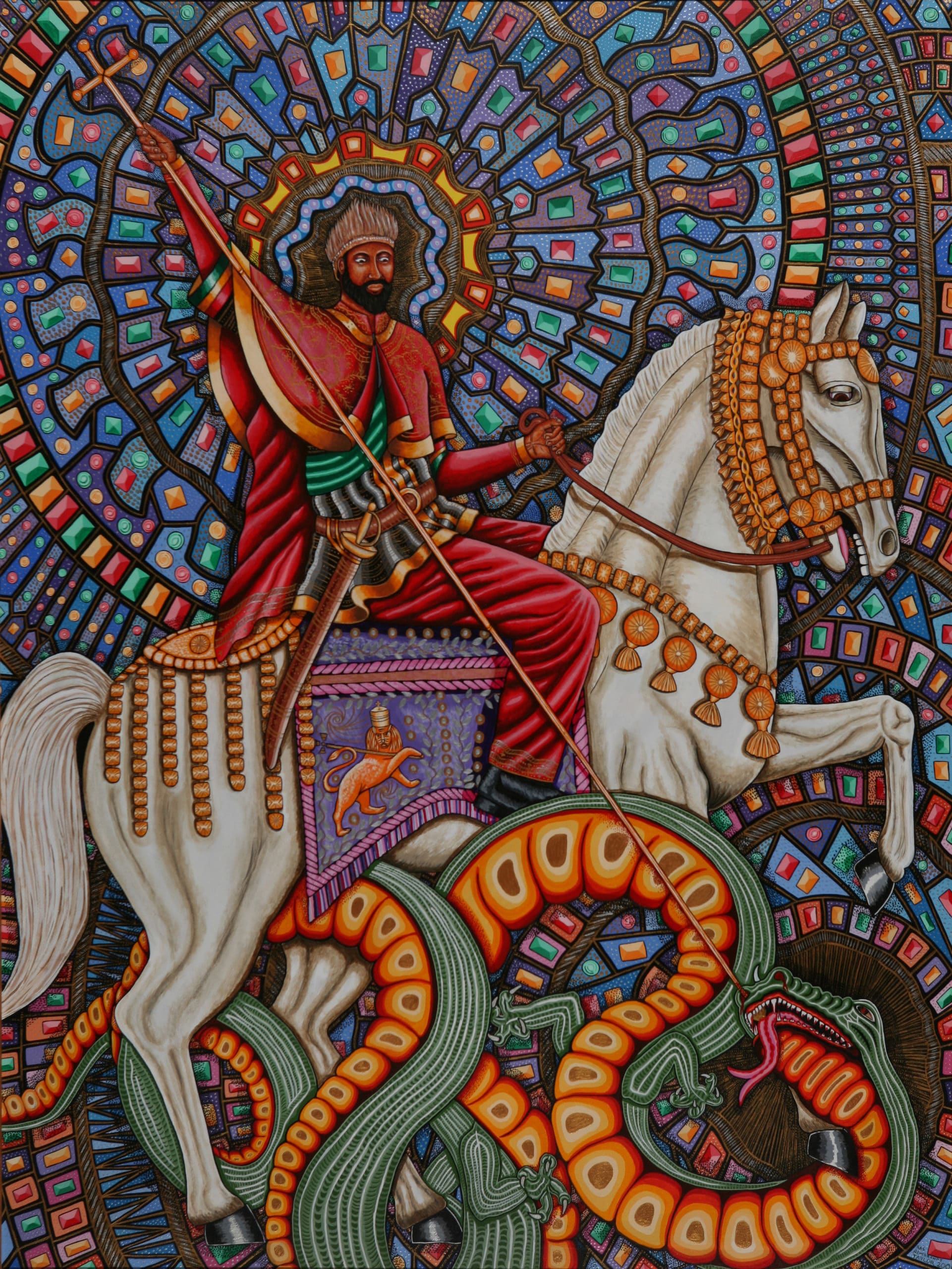

In this vein of celebration of Black histories of faith, “Defender of the Faith” (2001)—depicting St. George slaying the mythical dragon—would seem to be something of a contradiction. Why on Garvey’s green earth would a Rasta paint the patron saint of England in such detail? The image is iconic in art history, and the story is popular not just in England but across Europe – oddly enough, particularly in Russia and Georgia. Saint George, in Georgia, who’d have thunk it?

Throughout the centuries, depictions of old Georgie haven’t shied away from his potential origins. He is often shown as a dark curly haired, tan-skinned youth and is said to have been a young Roman soldier with Greek and Palestinian heritage. Though his image has often been made more fitting to what would be recognizable to the Europeans who celebrated him, he is still very much a celebrated figure in modern day Palestine, and Taylor’s image of the Christian martyr is more in keeping with the phenotypical traits that Saint George would have had given his background. He isn’t just tan, he’s nearing on brown, and his dark beard looks full of thick wavy tresses.

Rastafari is indeed rooted in Abrahamic religion and takes a very specific interpretation of the Bible as part of the faith. If God is Jah, then the same God that Britons look to in considering Saint George as a celebrated figure is the same Jah that the Rastafari look to. Taylor’s interpretation is taking a different lens to look at the same story, to show that the same man can be seen slightly differently depending on your vantage point. As the Rastafari movement seeks to empower and give justice to the Black diaspora, so then it makes sense that Taylor chooses to lend his hours of painting to deify Saint George in such a way that pays attention to the colour of his skin and the texture of his hair. George can be celebrated as a brown-skinned hero as much as the patron saint of a majority-white country.

The story of Saint George slaying the dragon takes place in Northern Africa, in Libya. The most popular telling of the story involves a small town that was plagued by a dragon and forced to make offerings to keep its venom (literal and metaphorical) at bay. From sheep, to men, to children, different lives were essentially given as sacrifices to keep the dragon from decimating the town. Ultimately, it became a sort of lottery as to who and what would be chosen to give to the bloodthirsty beast, much to the dismay of the King, whose daughter was chosen at random by said lottery. Though he offered every bit of gold he had to spare his daughter, the townspeople of course refused and so his daughter was sent to the pond where the creature dwelled, awaiting her fate. Christian iconography is replete throughout the story. If the dragon representing serpents and therefore representing Satan himself weren’t enough, the princess-sacrifice is dressed in white (as a bride to the church, and symbol of Christlike innocence) – making her a sacrificial lamb.

Installation shot of work by Rembrandt Taylor as seen in “Medium: Practices and Routes of Spirituality and Mysticism” on view at the NAGB through March 11th, 2018.

Saint George happens upon the scene and, though the princess begs him to spare his own life George, of course, being the brave and trained Roman soldier he is, stays and charges at the dragon on horseback, making the Sign of the Cross and stabbing the scaly beast with his lance. Soon thereafter, the wounded creature is given a leash fashioned from the princess’ girdle and the dragon – now “meek” – is paraded through the town as a horrifying message used to convince (see: scare) the townsfolk into converting to the Christian faith, as George very kindly offers to kill the dragon on the condition that everyone consents to becoming Christian and being baptised. And so it was that the people valued their lives over their pride and found themselves immersed in holy water with some good reptilian leather laying to waste in the distance, after the dragon is beheaded and carried out of the city. The king built a church in honour of the Virgin Mary and Saint George himself on the site of the dragon’s decapitation, giving the newly-converted townspeople the extra bonus of not just keeping their lives and land, but a lovely spring spouting water that cured all disease.

The story is fantastical for sure, but all great legends (and whatever magic and truths about human nature and the divine they might contain) should have some element of the unbelievable, they might not be worth telling otherwise. And, more importantly, these people become symbols of spiritual fortitude in times where we might be living in fear of practicing our respective faiths.

Taylor’s version of Saint George rides gallantly forth on a white horse adorned in the iconic Rasta lion and pierces the serpent-beast. He is surrounded by a halo of jewels and light, and the title “Defender of the Faith” (2001) gives the story the gravitas and glory he believes it deserves. The pedantic, ’90s computer style cell-shading of the man doesn’t just keep George in the realm of legend and Christian myth, but moves him almost into a digital realm, into the creative imaginings of Afrofuturism.

In light of recent events: the unveiling of a particularly pale and (some might suggest) anemic 3D model of the Queen Nefertiti, that the DNA tests of the oldest remains of a full human skeleton found in Britain (the Cheddar Man) show that this oldest fossilised human in Britain would have had brown skin, dark brown curly hair, and blue eyes, we are lead to look to the arbitrary nature of racial representation of a place or a time, and just how much that shakes us up. Rembrandt Taylor’s “Defender of the Faith” (2001) is a reminder that for many of us perhaps our racial alignment and sense of origin in a country isn’t quite as long-reaching as we once thought. And so then, why do some of us feel threatened by it?

The Caribbean is a region built on the idea of a lack of long-standing origin tied to a particular space, and this discomfort leads to unlimited possibilities for freedom of the mind – because without ties, what can we do but fly and move? This tension of European colonial heritage with the celebration of afrocentricity that Taylor balances in his work is telling of, not only the Rastafari movement, but the social difficulties in the Caribbean that lead to its inception. In moving through these difficulties and in seeing empowering images such as those paintings signed by this self-taught wonder, “Ras Rembrandt Taylor”, we might look to see that while race is always going to shape us, these antiquated ideas of origins and whose-space-is-whose do not serve anyone.