Dialect and Diaspora: The Intuitive Art of Joseph ‘Joe Monks’ Weaver

Natalie Willis ·

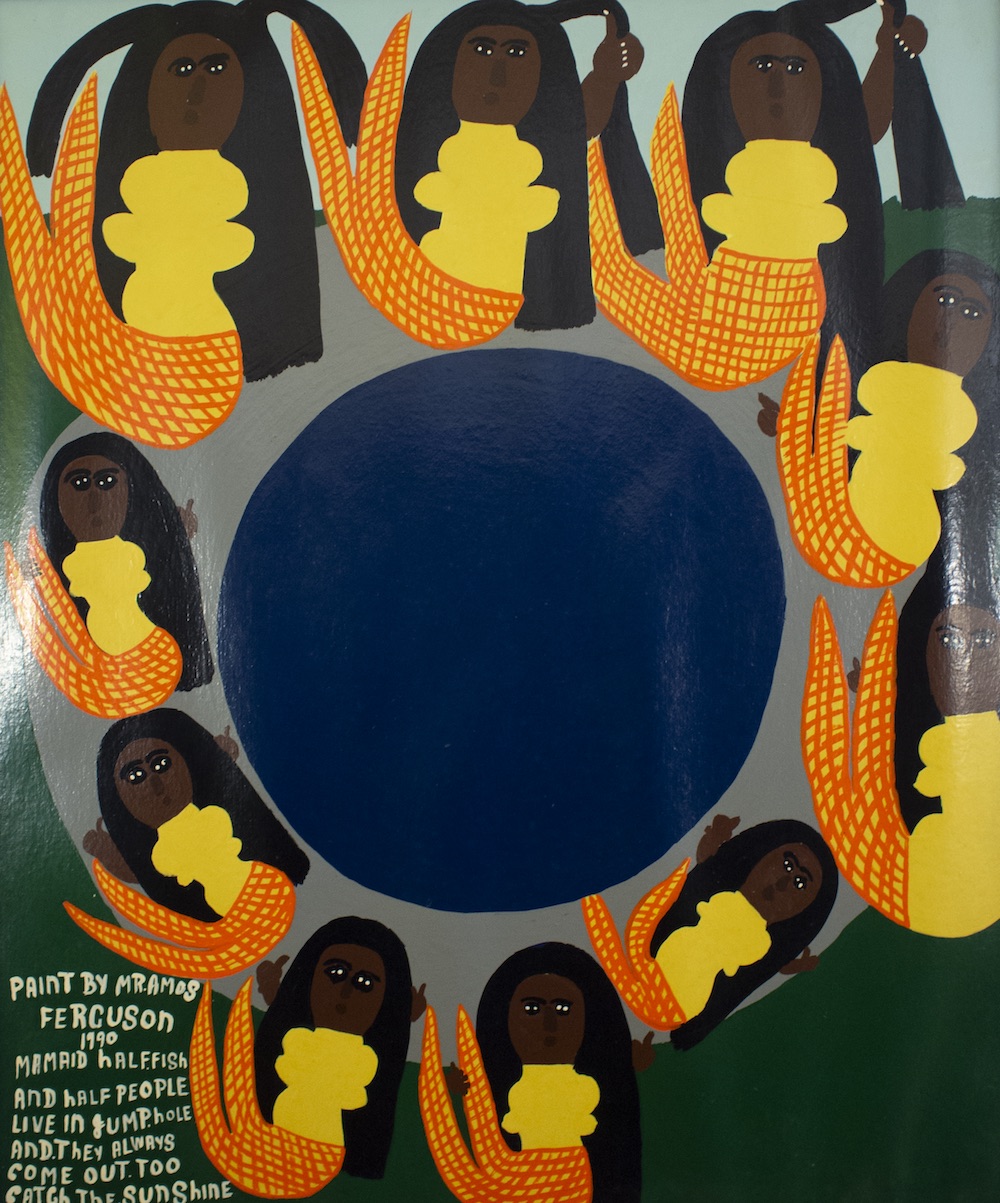

As the current Permanent Exhibition, Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean comes to a close next month, it’s an apt time to review one of the key themes that resonated with many during our tours and casual chats here at the museum. We love to speak about how special, confusing, and linguistically interesting our Bahamian dialect is, but one of the questions posed in this exhibition in the section titled Dialeck [sic] gives us a moment to think on what our visual dialect could look like. When we look at the work of intuitive artists such as Amos Ferguson, Netica ‘Nettie’ Symonette, or Joseph ‘Joe Monks’ Weaver, we see just that – people who move beyond the “proper grammar” of Eurocentric art history and the canon of art practice, choosing instead to communicate in an art dialect of their own making.

Intuitive art is an important part of art history – not to “supplement” the way we see more widely accepted practices in art, but as art in and of itself. If we do not value the work made by people who haven’t undergone tertiary education, then we do our culture and creative community a serious disservice. There is equal need for the work of those who study art at university, who learn how to translate their practice for wider audiences in the commonly understood visual lingua franca of modern and contemporary art, as well as those intuitives who speak for the wider population and to what our creativity looks like as it evolves directly from our space and communities outside of institution.

Joseph ‘Joe Monks’ Weaver is one such artist. Thanks to the biographies in “Love & Responsibility: The Dawn Davies Collection” (2012), we can gather a few things about Weaver’s background. Born in 1901 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he lived with his mother in Miami Beach, Florida for the majority of his schooling. The history of Bahamians in Florida goes back further than many of us may realise, as was highlighted in our recent talk with the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens team just last week. Bahamians have been living and working in Florida since the mid 1800s. From the 19th-century Bahamians who were either land-owners or making a living from wrecking and treasure-hunting, to 20th-century agricultural workers on The Contract living through the Jim Crow era’s racial segregation, we have been intricately tied to the history of the “Orange State”. By and large, Bahamians were an integral part of the building of communities like Coconut Grove and our diaspora’s history runs deep in the state. Weaver is a part of this history and his time in the US along with his move to the islands are part of this migration of Bahamians back and forth between the two spaces.

‘Joe Monks’ Weaver, on view in the current Permanent Exhibition Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean

Weaver moved to Nassau in 1917, when he was sixteen years old, and he remained here for the majority of his life excepting for a brief period in the late ‘50s, when he lived in Rock Sound, Eleuthera. His experience of Americanness was surrounded by Bahamianness and his time here would have undoubtedly thrown his ambiguity as an American-Bahamian into sharp relief. He was described as a “fearsome man who regularly disturbed the peace”, having served time in prison and the Sandilands Hospital, where he spent his last few years in the Geriatrics Ward. Trained as a stonemason, Weaver is said to have worked on the walls at Government House and at the Police Barracks on East Street, along with possible work at St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral where his time with the monks is believed to have been the source of his nickname.

A true intuitive, Weaver didn’t receive much formal recognition from institutions during his lifetime as a self-taught artist, with his first solo show taking place at the now-closed Bahamas Art Gallery, when he was 91 years old. He worked largely in paint, pencil, ballpoint pen and crayon on paper, with wax peeking purposefully through layers of acrylic or layering to give texture and body to the scenes of Nassau that he would have grown up with and watched change over his 70 years here. He used materials available to him, he quite literally penned his name on his work, and his gestural, flattened perspective gives us a moment to see these iconic buildings, harbours, and bridges in a new light.

Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean is on view at the NAGB in the downstairs galleries until 2 June 2019. The museum is free to all locals on Sundays, with our Fourth Sundays coming up on 26 May where you can join a free guided tour.