Epistemic and Cultural Violence: Powercutting as Light

Anibal Quijano (May 31, 2019) and Toni Morrison (August 5, 2019), two great thinkers have gone. Nicolette Bethel’s 1990 play, Powercut, produced and performed at the Dundas Centre for the Performing Arts, shows what happens in the dark. Nowadays, lights drop into darkness at least once a day for hours at a time. The violence of structures invisible to the naked colonised eye is only ever gossiped about. We are afraid to cease being what we are not, we do not know how to be who we are. It is the culture of violence and silence revealed through ‘discussions’ around tourism and prostitution, two interlocked economies of pleasure. The Victorian Bahamas avoids discussing these things in the same breath, yet the exoticisation and tropicalisation of space and place speaks to a reality of total erasure of self for what we are not, to pick up on Quijano’s statement.

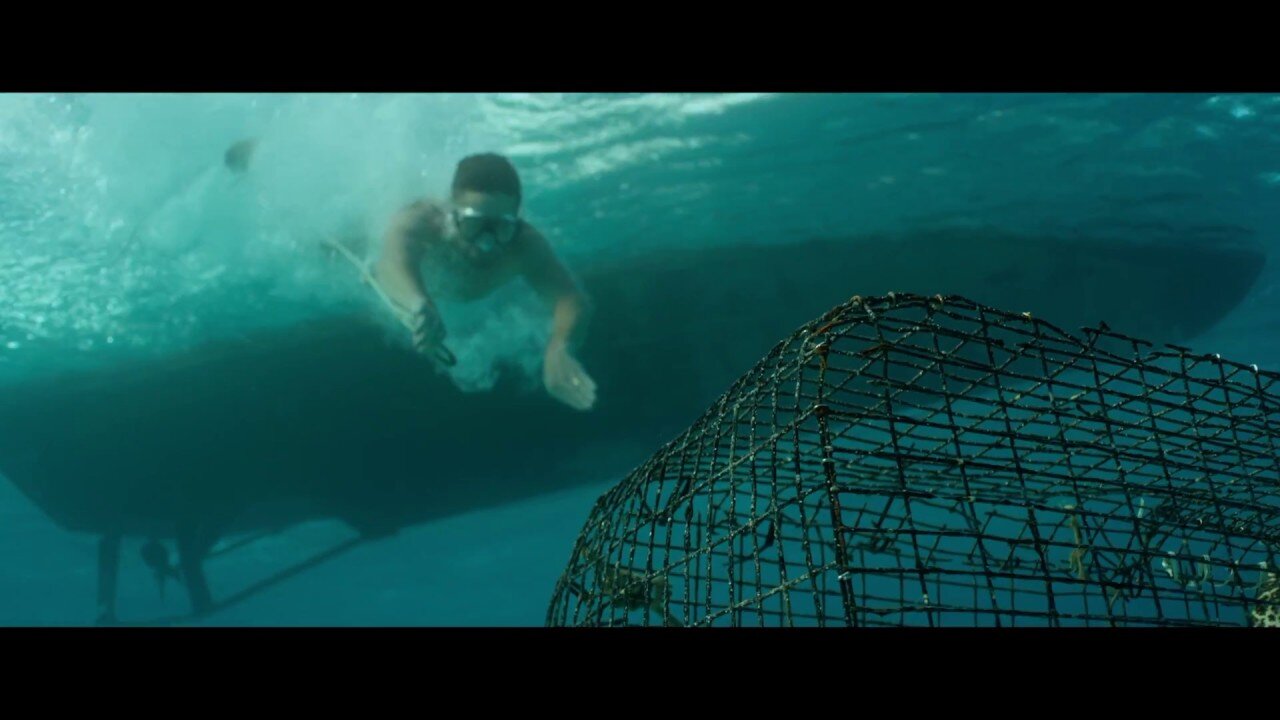

In The Visual Life Of Social Affliction, the upcoming Small Axe Project exhibition which opens at the NAGB on Thursday, August 22, 2019, we see what we are taught/made not to see; we see the violence of not seeing who we are and the trauma of being held in bondage through invisible structures. Powercut reveals a lot of the invisible structures as do the works of recently departed thinkers Anibal Quijano and Toni Morrison.“It is as if I had been looking at a fishbowl — the glide and flick of the golden scales, the green tip, the bolt of white careening back from the gills; the castles at the bottom, surrounded by pebbles and tiny, intricate fronds of green; the barely disturbed water, the flecks of waste and food, the tranquil bubbles traveling to the surface — and suddenly I saw the bowl, the structure that transparently (and invisibly) permits the ordered life it contains to exist in the larger world.” —Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992).

Morrison reveals our own cultural structures of control, yet we choose not to see without averting our eyes. As Morrison, the incredible creative writer of Beloved (1987), a painful and disturbing book about slavery and reconstruction in the American South, pens in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, she demonstrates how whiteness is assumed to be the point of departure and initiation, much as Quijano does in La Colonialidad del Poder (2000); they discuss coloniality and literary and literal whiteness that normalises racism because anything not white is preculture, prehistory. We imitate what we are told we should be, Quijano argues:

“Consequently, when we look in our Eurocentric mirror, the image that we see is not just composite, but also necessarily partial and distorted. Here the tragedy is that we have all been led, knowingly or not, wanting it or not, to see and accept that image as our own and as belonging to us alone. In this way, we continue being what we are not. And as a result, we can never identify our true problems, much less resolve them, except in a partial and distorted way.” Quijano’s La Colonialidad del Poder.

In 1968 Frantz Fanon states “The native is an oppressed person whose permanent dream is to become the persecutor.” As the lights go off, darkness descends and violence engulfs our nights, we are told to sit quietly and listen to our betters. The coloniality of power means that public servants refuse to engage with the public; such is the social affliction of the post-colony. The silence of loss is never easy to swallow as it dries one’s mouth and burns the gullet descending.

Loss is complex and signifies a kind of erasure from space, the removal or shifting of words so that the meaning can change, but also the beauty of nature can be vanished through the engineering of space. Violence and space, a special issue of Political Geography is helpful in this regard because it talks about the geographies of violence. Further, loss as Melvin Alavrez shows in his master’s thesis from Rhode Island University, that the violence of beach enclosures affects in multiple ways. Certainly, blackouts/powercuts create violence and strife, dis-ease, and dissatisfaction; they breed discontent and dysfunction. The violence of blackouts is that they are a cultural sign of erasure, overpressure and climate change due to rising waters causing disappearing lands.

As what was once called The Bahamas Electricity Corporation, now effectively privatised and renamed, though the Gazette may not mention this, to BPL, has left a bad taste in the mouths and poisoned lips curled in disgust. This venom seeps from lip to ear as gossip sizzles through the marketplace, and servants of the people turn their backs on those fools and stare into the sun. Of course, their retinas may be burnt out, but better not to see. Art and culture have become synonymous with healing and expression. Yet culture, the culture in which we live, is often a space or place of violent erasure. Silence is only golden as one chokes on it. The silence of structures of violence is never overwhelming because the tumbleweed blowing down the abandoned road of island living shows the lack of imagination being allowed to grow in this space. Perhaps this moment will bring creativity and create an artistic flow that flourishes in the dark and cannot be produced by electricity dependent media.The need for quiet darkness maybe enough to instigate fertile imagination of literary and visual expression. Today, to imagine one must create dangerously. Our imaginings and imagings are one step away from gone. As Quijano observes of all those who preexisted Europeans in the Americas, “[t]three hundred years later, all of them had become merged into a single identity: Indians”. In North America where most “Indians” have been stripped of their land and identities, and sent to inhabit reservations where their rights are limited by their lack of citizenship. Similarly in The Bahamas, “Ashantis, Yorubas, Zulus, Congos, Bacongos, and others. In the span of three hundred years, all of them were Negroes or blacks” (Quijano, p. 574) the erasure is all but complete and the structures of nationalism and coloniality are seen in the fishbowl, though we have been blinded to them. The power cutting may reveal more than we can imagine.

The Visual Life of Social Affliction opens at the NAGB on Thursday, August 22 at 7 pm. All are invited to attend.