By Natalie Willis.

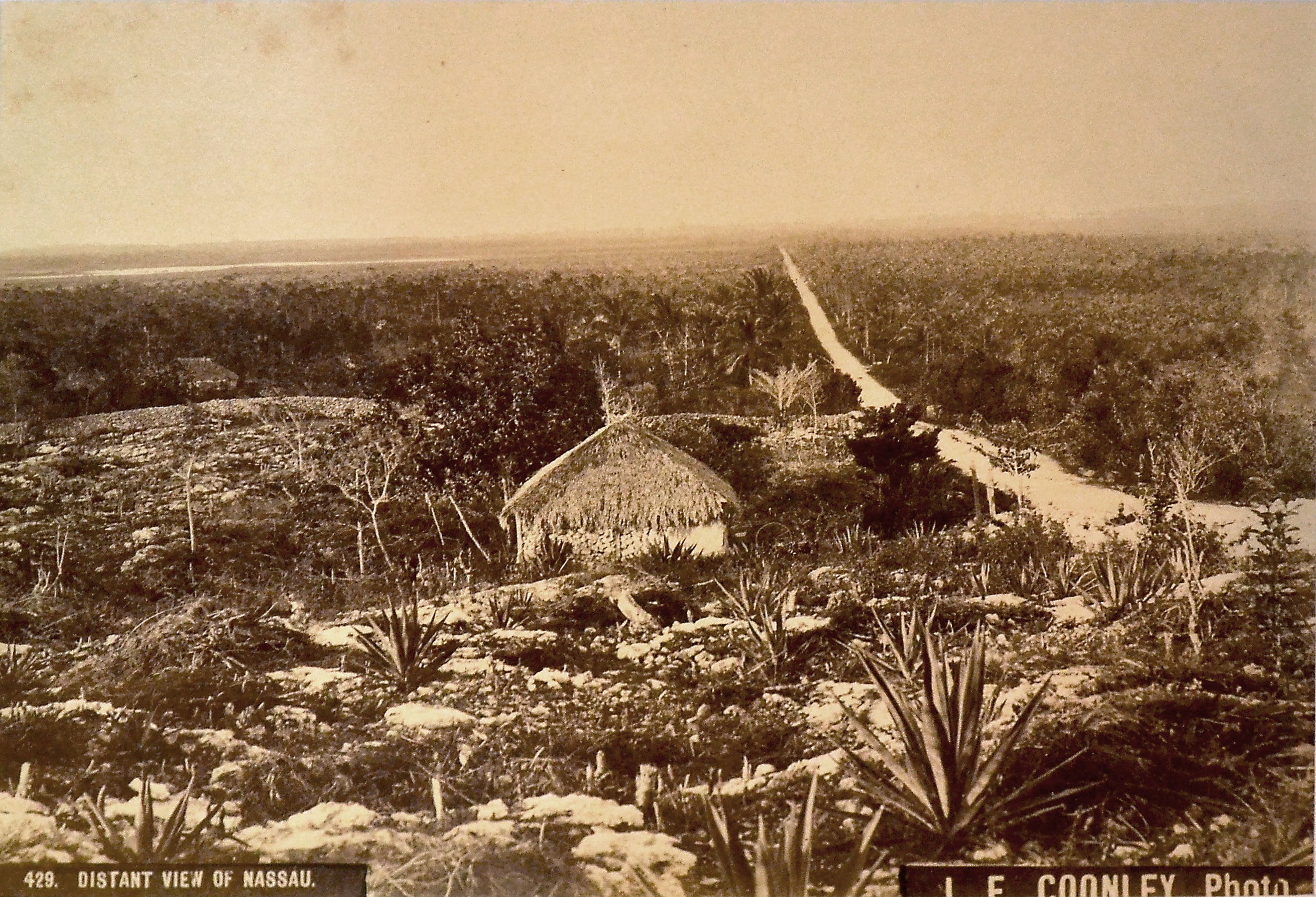

Looking at this photograph, “distant” is certainly apt in different facets of the word. It is a distant, far off view. It is a distant time, a bygone era. It is also a distant idea to think of Nassau in this way – so largely uninhabited with stretches of green bush for miles, sisal and rocky paths to illustrate this difficult land – formerly difficult for our floral inhabitants, now harder for the people living in what feels like harsh social terrain. The reactions witnessed to this image are very telling, the astonishment on locals faces when they try to imagine a Nassau like this seems like having to tell someone to imagine us in prehistoric times, not just over 200 years ago. That surprise speaks to the way the development has become so utterly integral to our identity in the capital, and truly the country as a whole.

We know in better detail now the way that The Bahamas, and the Caribbean basin as a whole – this rich bowl that fed and sustained so many mouths across the world during the age of Empire – was a place produced and manufactured, and dealing in production. The sisal we see scattered is a symbol not just of Nassau before our British colonial history, but also of the thick of this history – sisal was one of the few crops that thrived on the rocky limestone isles and made a roaring business… for a time.

John Northrop of Columbia College, wrote “Cultivation of Sisal in The Bahamas” back in 1891 for the Popular Science Monthly journal (volume 38) stating: “The group of coral islands known as The Bahamas lies east of southern Florida and north of Cuba. One of the islands, New Providence, is well known to those who, in search of health or recreation, have been to Nassau and enjoyed its lovely winter climate. But the “out islands,” as the remaining ones are locally termed, are seldom visited, even by those who live in Nassau. The largest of these “out islands” is Andros, which is about the size of Long Island, New York; there, as in all the others of the group, except New Providence, the population is almost entirely composed of negroes, only seven white men living on the island; and of these, four are interested in the production of the fiber known as sisal hemp.”

Forgiving the uncomfortable, dated language – as Northrop is inescapably a product of his time – and the fact that Andros is actually considerably larger than Long Island, the dedication to writing to our sisal industry was clearly of great interest and intrigue for businessmen abroad looking for this crop that, at the time, “is in its infancy in The Bahamas, but, if the present prospects are realized, it will before long bring to the islands both wealth and prosperity.” Sisal and pineapple are two of the only agricultural industries that sustained success for a lengthy period (but only by comparison to our other short-lived attempts). This foreign interest is something we know all too well today, it is a theme that has continued for centuries and remains the driving force behind shaping our nation. As a place built on tourism to begin with, how can we begin to imagine any differently? Of course, there were those who sought religious freedom here, and the ‘golden age of piracy’ that played its part, but slavery and the subsequent reshaping of Nassau into a tourist idyll are the vestiges of colonialism that we have internalised to our core. And when we think to how we still have plantation houses left today, plantations that very well could have been sisal, it is a reminder of the history at play when we look from these old ruins to the hollow concrete, styrofoam, and plaster structures of hotels we see today.

Jacob Coonley, William Henry Jackson, and the Eleutheran James “Doc” Sands all play a large part in helping us piece together our history. While many take these old photos at face value as a way to show us how places used to look, such as this image of Nassau, they have far more worth in showing us how we were seen.

As Krista Thompson concludes in the text for the “Bahamian Visions: Photographs 1870-1920” exhibition at the gallery in 2003, “The photographs included in the exhibition demonstrate that a single image frequently circulated for over half a century [became] representative of The Bahamas… Through the repetition of such images a long-lasting visual idea of the island became consolidated and popularised… It is easy to view photographs as objective documents of the past, even though, as we have seen, frequently photographers were very selective in their choice of subject-matter and in their construction of the photographic image of picturesque Nassau.”

Having our landscape changed so drastically by the interests of others, shaping things to make ourselves available as if rouging ourselves for sale in the evening, has been our history for as long as we have had a ‘decent’ (for the time) sized population. Does our anger at seeing a lack of Bahamian investment upset us for the xenophobia we hold close, for the lack of opportunity we see thanks to corruption and brain-drain, or is it a knee jerk reaction to feeling perpetually at the whim of others with means for the past few hundred years? Perhaps we have cultivated all three.