By Natalie Willis.

“A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) by William Henry Jackson is part of the suite of historic colonial photographs in the National Collection. Jackson was an American, who started a photo studio here after emigrating from New York in the 1870s and is one of the small group of colonial migrants whose pictures help us piece together part of the story of the time. According to the catalogue for “Bahamian Visions: Photographs 1870 – 1920,” curated by Krista Thompson, Jackson first came to The Bahamas at the request of the Governor of the time, Sir William Robinson, in 1877. Since around 1856, Jackson worked as a landscape painter, colourist of photographs and also owned a studio specialising in Daguerreotype photographs. In addition, he manufactured albumenized paper, managed a stereoscopic printing shop and had even worked as a Civil War photographer. Many of these things seem very far removed from us now, but they were staples of photography at the time.

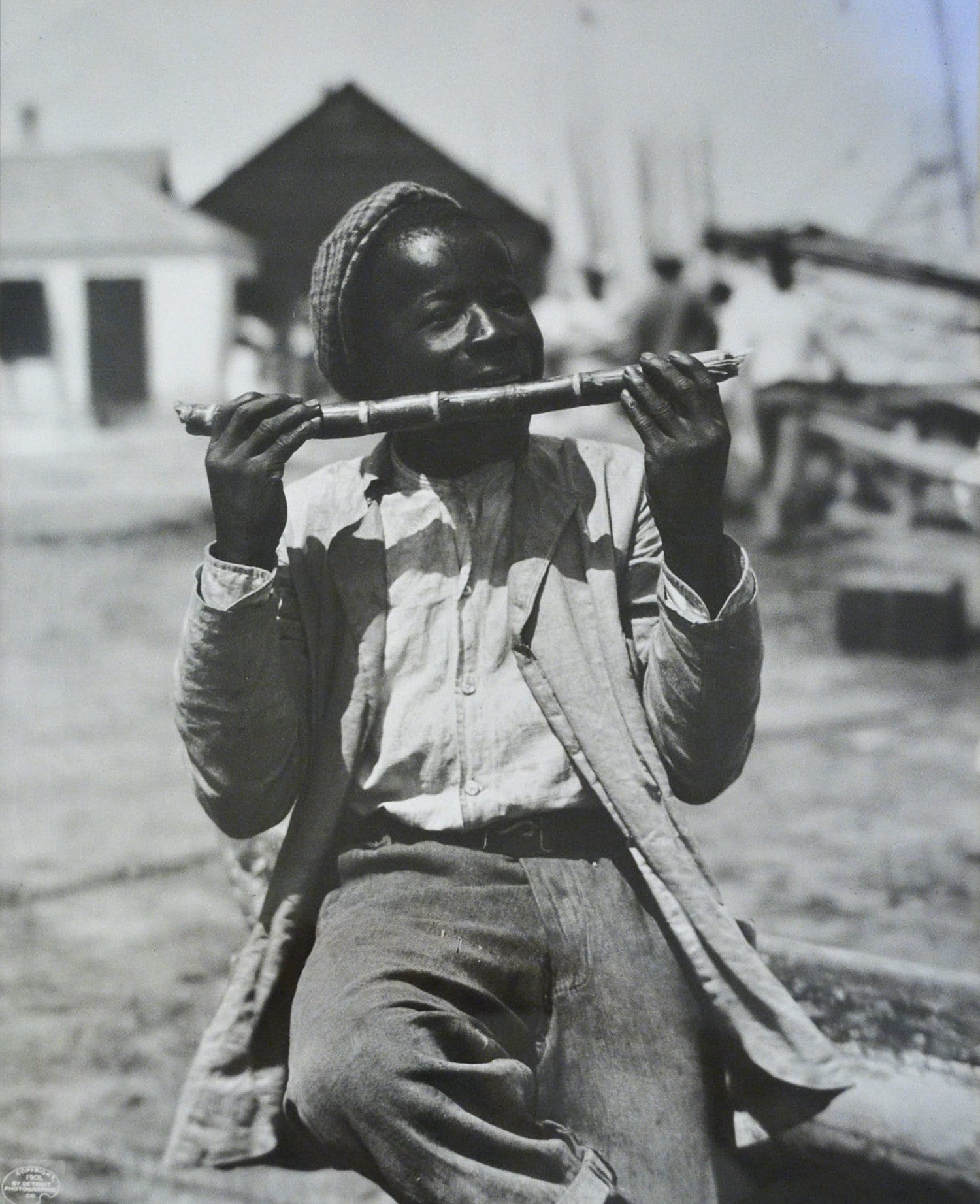

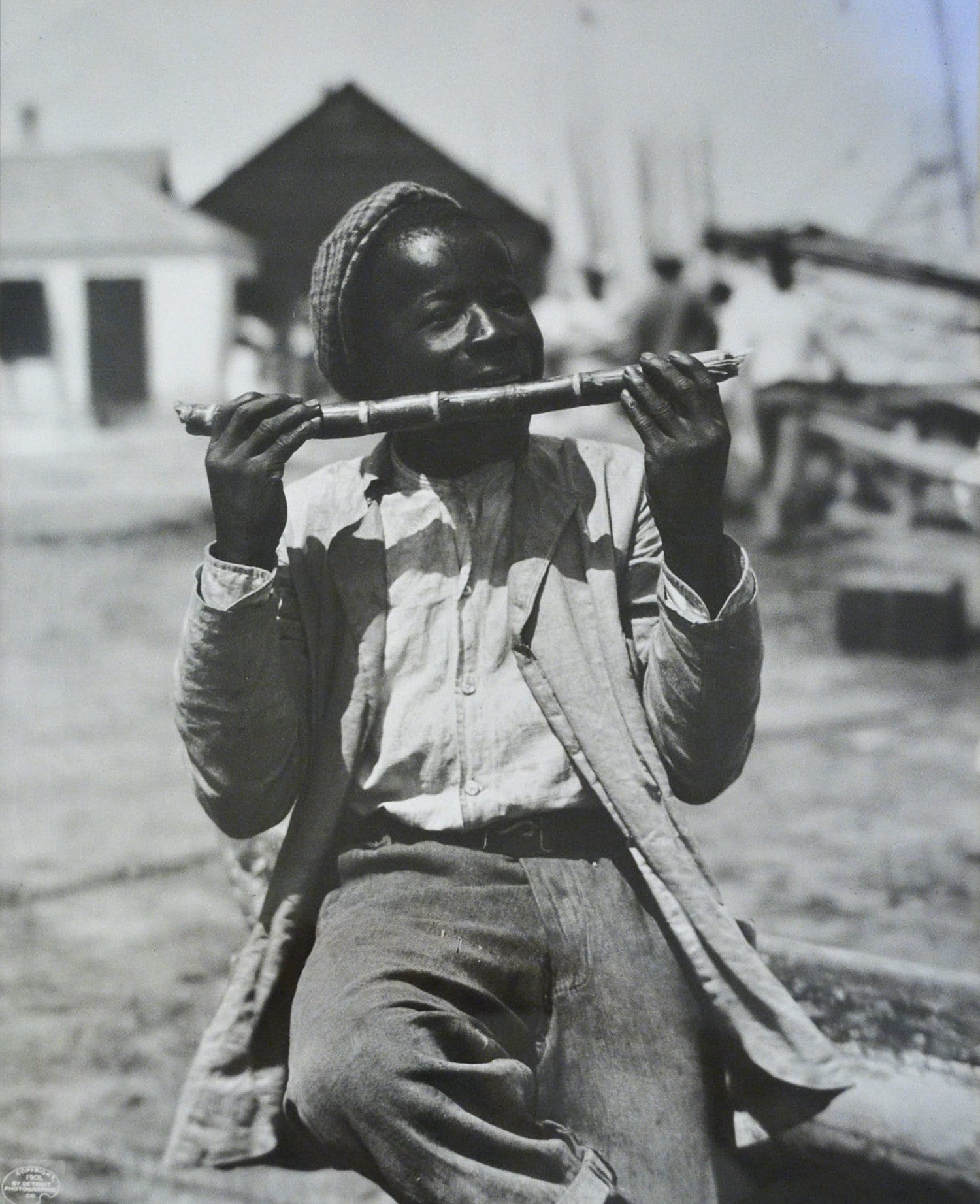

“A Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901) shows a young Bahamian man of African descent, perhaps no more than 15, chewing on sugar cane – part and parcel of the culture here and one of those indulgences in summer. Sweet cane, chopped up and stored in the fridge so it’s nice and cold, any Bahamian can relate – even if things were more than a little different in this young man’s time. If the title of this photograph is amusing to you, or if you find it disconcerting, then that’s precisely what this piece about: the complexities of language and perspective.

There is a lot of contention around the word ‘native,’ and rightfully so given the context of how it has been used throughout history to denounce indigenous peoples as lesser, as ‘savages’ when compared to the ‘civilised’ European populace of old. We still feel the sting here as Bahamians with roots to West Africa—although we are not the ‘original’ Bahamians here since that esteemed position goes to the Lucayans and Arawaks, who were decimated during the first unfortunate wave of colonial activity. Looking further, the idea of giving a name to a photograph and insinuating that a black boy is a ‘sugar mill,’ given our regional history of slavery, it is clear that this naming does not acknowledge the humanity of the boy’s presence or allow for him to be read as a legitimate subject. The racist undertone of this is impossible to ignore making things even more difficult to swallow.

[]

“Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901), William Henry Jackson, Original glass plate print on archival paper, 11 x 14. Part of the National Collection.

The word ‘native,’ from the mid 15th century, was generally meant a ‘person born in bondage or servitude’ or, in the 1530s, as a ‘person who has always lived in a place.’ There’s a rather big divide there in meaning and that only became more complicated in the mid-17th century, when it was used to convey a difference between original inhabitants of non-European countries where Europeans held political power – particularly when thinking of First Nations peoples in the Americas. It became a derogatory way to refer to local people. So here we see that from the early 15th Centuries, hundreds of years before this image was taken, the word “native” takes root in some very unfortunate connotations.

The young man we see holds his gaze to the lens, which can almost be seen as defiant, cheeky even, and yet he is still posed – because, really, who eats sugar cane like this? It isn’t practical, for certain. This plucky youth still holds his pose, still looks at the camera, but he seems to have a confidence or blissful ignorance about him – was he so used to the way he was looked at by the gentry or the upper classes that this seemed normal? Was Jackson kind in the way that he spoke to him? Was the young man entertaining Jackson because their races didn’t ordinarily mix and he was being asked to pose for the camera – for what was perhaps one of the first and only pictures in his life? There are so many questions to be asked and to be answered.

There is always this assumed sense of ‘objectivity’ with lens-based media – cinematic and photographic-based images, produced on film or glass plates originally as this work is. It’s odd, really, because when we see our world reflected to us we assume it is a mirror and not a lens. Mirrors reflect your image back to you and so can photographs, that’s for certain, but looking through a lens and looking into a mirror are two entirely different activities. Mirrors frame your image in real life to you, and the lens is something you frame yourself, choosing what to photograph; you choose what moments are worth recording, you choose just how you want something to look. Media is not a mirror.

On the popular medium of TV, we see ourselves as Caribbean people represented as Rastas, with Jamaican accents and either wise givers of knowledge or as drug-running gangsters – oh yes, and of course marijuana and rum, we mustn’t forget that the image isn’t complete for us without some form of intoxicant to denote how the islands are such a ‘good time.’ If we can see that this image isn’t really us in our complexity, why do we look to these old photographs as truth?

This technology of the time was the way we could send information and thus dictated what was recorded. As Donna Haraway, the feminist scholar, illustrates to us in her text ‘Situated Knowledges’ (1988), “Technology is not neutral. We’re inside of what we make, and it’s inside of us. We’re living in a world of connections — and it matters which ones get made and unmade.” Much like historiography – the way history gets written rather than history itself – it is rooted in its subjectivities. The idea that anything human can be objective is a falsity, as we are all shaped by our experiences, privileges (and lack thereof), and interactions throughout our lifetimes in an intertext of human relations. The significance of certain representations relates more to what groups held power in history than of what was truly ‘important’ to the masses. The ‘how we were seen’ rather than the actuality of how we truly ‘looked’ at the time.

Further, as John Berger had put in “Ways of Seeing” (1972), we forget that what we take as default is always our social conditioning – and more often than not, for the worse of our fellow man and woman. “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting “Vanity,” thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.” Had Berger been looking at Jackson’s photo, he could perhaps say “you photographed a young black man because you enjoyed looking at him, put the cane he grew for you in his hand and called the photograph “Native Sugar Mill,” thus condemning the boy whose blackness you exoticised for your own pleasure.”

‘Native’ to this young man – unnamed, as so many everyday people were in this time – compared to how Jackson would have viewed the word were two entirely different things, let alone how that word fits into our personal contexts now. In Jackson’s time, there was this prevailing idea that brown peoples were ‘savages’ and ‘uncivilised’ – though how the idea of barging into someone’s homeland and telling them to believe what you believe and how to behave in their own home as a way of being ‘civilised’ or as ‘civilising others’ is beyond many of us in this era.

Still, certain things don’t discriminate and certain foods definitely humble us all. Nobody looks elegant eating sugar cane. Juice drips down the most dandy of chins and jaws gnash away at the fibres regardless of creed, class, or colour. Cane don’t care and we would do to remember that in our own lives.