By Natalie Willis.

“Built on Sand,” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin-Smith, is in some ways the sister work to “Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink,” (2003). Both works are of the same dimensions, which instantly makes us as viewers try to compare them and view them in the same plane when they are placed near each other, but, it is the critique and use of religion as their subject that makes them read like chapters in a book, feeding into each other and helping to inform a greater whole.

Also, acquired in 2003 at the inception of the NAGB, “Built on Sand” is a testament, if you’ll forgive the pun, to Benjamin-Smith’s work in regards to her criticality of Bahamian social conditions. As mentioned last week, she is a creative practitioner, who works as both a visual artist and a graphic artist, and who proudly identifies as Christian as so many Bahamians do. She has an accessibility in her spirit and life, as well as her practice, and communication is, of course, key.

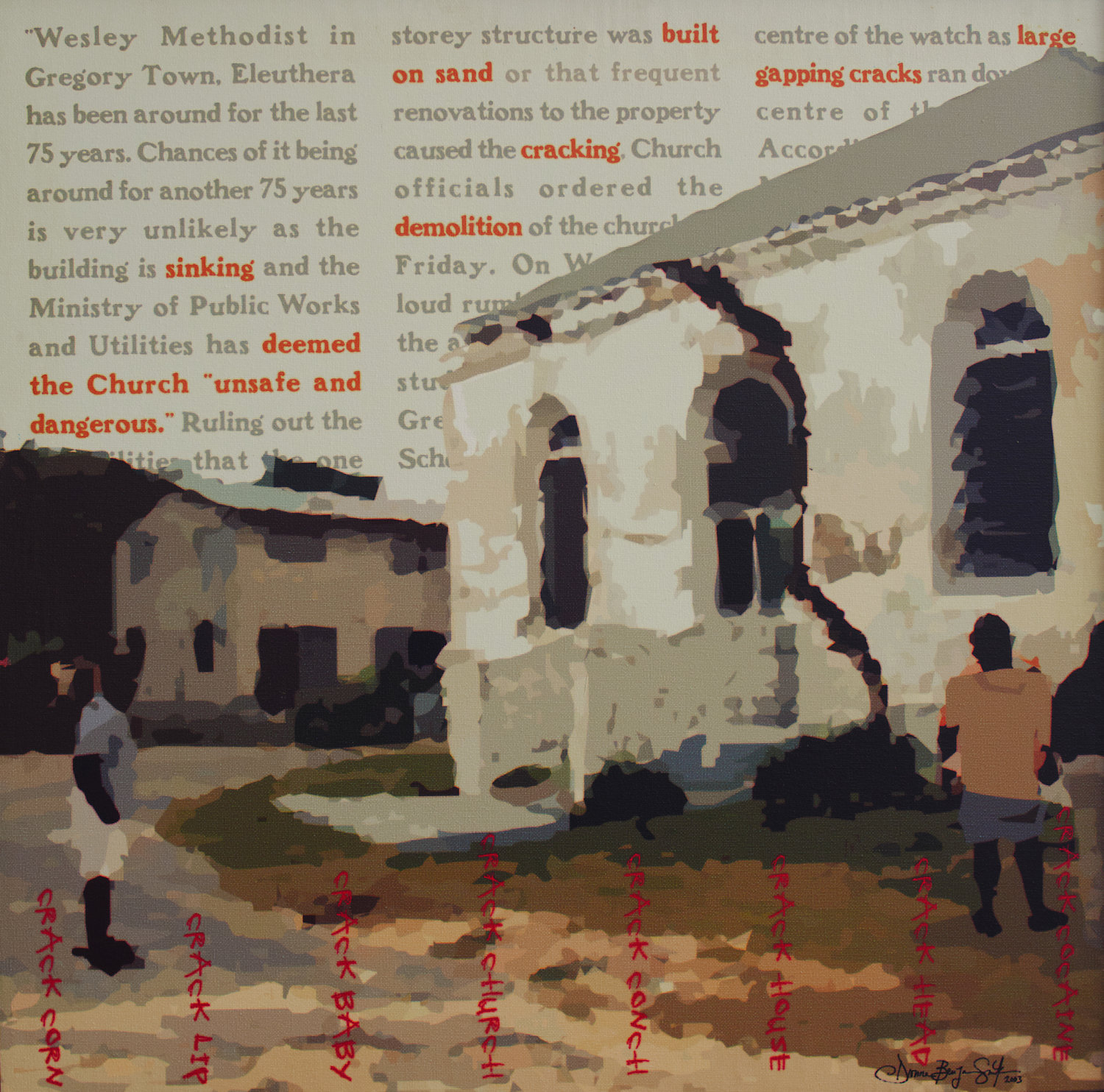

“Built on Sand” (2003), Dionne Benjamin Smith, digital print, 24 x 24, the National Collection (courtesy of the 2003 Collection Fund).

The piece started out of ruminations on an article that Benjamin-Smith read in the paper featuring a photo of an Eleutheran church that “developed a large and devastating crack” that extended from the foundation to the roof. How could something so symbolic not call for artistic interpretation and metaphor?

Speaking with her she shared: “The crack that broke this church in half was indicative to me of the state of affairs of “The Church” as a whole in The Bahamas. Between some “men of God” being exposed as adulterers and paedophiles, to church-folk back-biting and tearing each other down, to pastors leading their flock into all kinds of questionable dogma and situations, there was very little Christianity being demonstrated anywhere.”

The image itself looks post-apocalyptic, with its grey and washed out sepia tones and the striking red lettering between. Putting an image like this and having it printed on canvas acts as a statement on the history of art and religious iconography. We think of the way that paintings of the Renaissance or the Enlightenment in Europe painstakingly depicted Christian scenes in oil on canvas (as well as illuminated manuscripts or on the ceilings of churches) as a way to help us imagine the divine and to see it for ourselves. It’s quite biting that she uses canvas in this way, given this history, and helps drive the critique further home. Fitting it into even deeper context, the fact that it is currently displayed across the road from a historic church–St. Francis Xavier Cathedral–makes it feel even more pertinent.

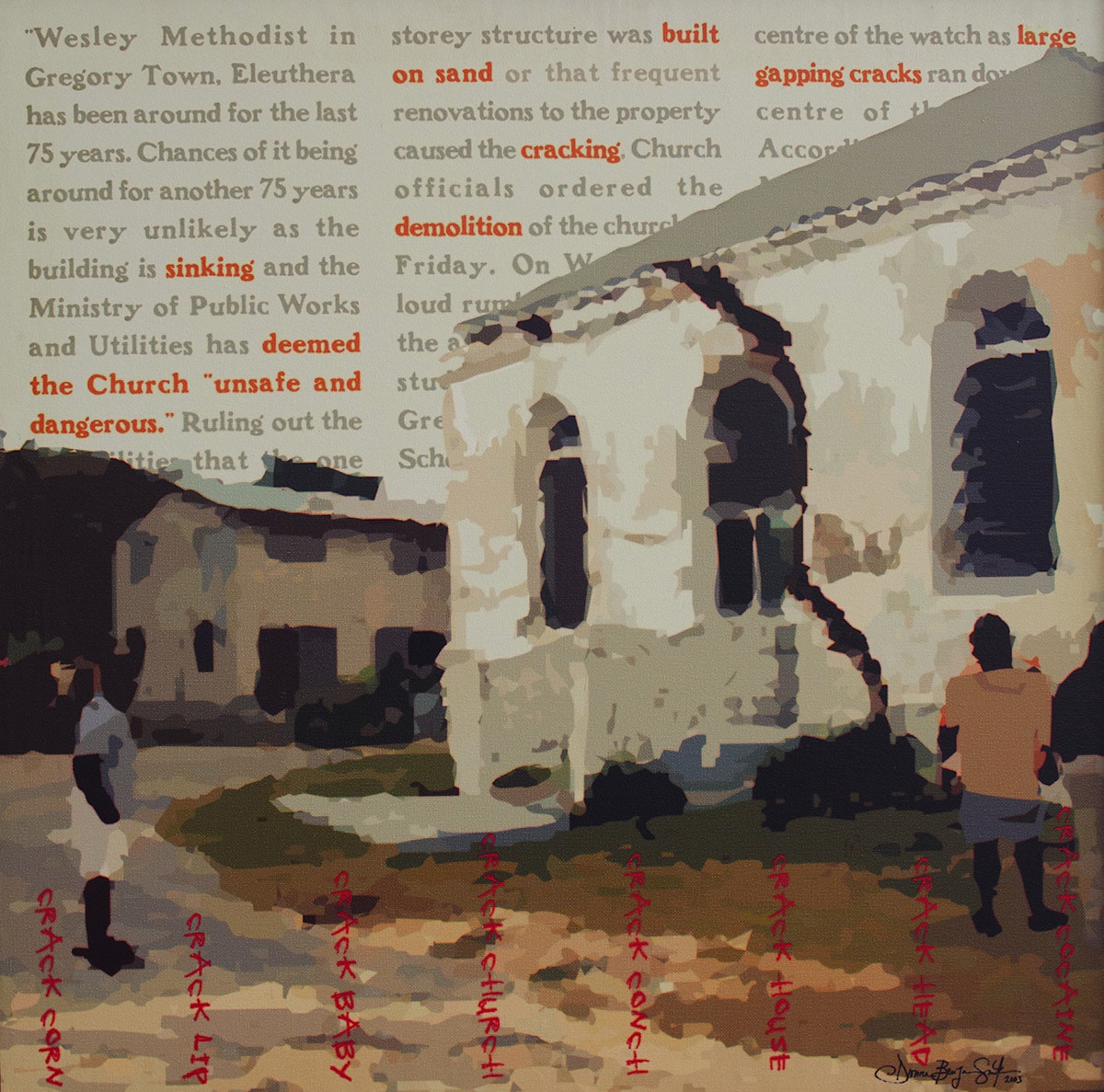

Installation view of “Built on Sand” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin Smith. Part of the National Collection.

“(The) article and photo represented the state of affairs as I saw it. The words of the article are showcased (in the work), and certain words are highlighted for added meaning. As relayed in the Bible, a house that is built on sand does not stand. The actual event of this little church breaking open from its foundation is almost prophetic and is representative of this scripture – the church falls apart when its teachings and true purpose are cracked and warped.”

When looking to the corruption inherent within the religious figures imagined for “Bishops, bishops… “ , and the statement of the cracked, corrupted church of “Built on Sand,” the works reinforce each other and bolster each other’s messages in a strength, almost functioning as a diptych (a single artwork made up of two separate pieces that function together as a single object) . The church, as many of us learn, is the people not the building – but the building is representative of the coming together of the body of people, and is the vessel that houses this community. When the body is “rotten,” not unlike the portrait of Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s tale, we can only hide the decay for so long before it becomes apparent.

Installation view of “Built on Sand” (2003) and “Bishops, bishops everywhere and not a drop to drink” (2003) by Dionne Benjamin Smith. Part of the National Collection.

It feels taboo to discuss this in “polite company” and, as a people, we often hold such pride in our faith that we find it hard to critique the problems inherent within it. Benjamin-Smith’s work acts as a site of faith in how it opens up discussion and discourse on the problems of the Christian faith here – and for more than a simple acknowledgement. Her works become discussion pieces and that discussion is how we begin to find ways to move forward, to accept difficult histories, to try to change.

Art isn’t always the activist it’s intended to be, but it would be remiss to think that making bold statements like this don’t cause some change, even if it’s just on a personal level by experiencing it in a gallery, a ‘sacred’ space of thought for some. Silence is violence, as they say, and opening up a place for dialogue and laying bare the problems we face a good place to start.

We can sometimes feel that this dominant faith in the nation is itself built upon sand, given its difficult colonial history and our lack of historic ties to those practices on the part of our West African ancestors or our indigenous people, but it is also a metaphor for the shiftiness of where we place our identities in this history as well. This movement of sand, washing with the tide, accreting with new material over time, is a poignant message for how to view ourselves.