By Natalie Willis.

The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas

Who gets to write history? And, better still, who gets to interpret it, present it, share it to the masses?

It’s a slippery question for the Caribbean, and arguably for most post-colonial countries. Much of what makes it so difficult to grasp is how the gaze is problematised in this region. In art and history in particular, “the gaze” as a concept is the way that our history, experiences and dominant narratives shape the way we see – in short, it is how our conditioning as a society influences the way we view ourselves and others. In particular, film and cinema capitalise on this with the way they place certain visual cues. At its best, it can be a way to build suspense and intensity in film, at worst – and as so often happens with Caribbean history – it can drive in a singular narrative on what is a very nuanced experience. Tamika Galanis’ Returning the Gaze: I ga gee you what you lookin’ for (2018) explores just that: representations of Blackness outside of a dated, colonial gaze.

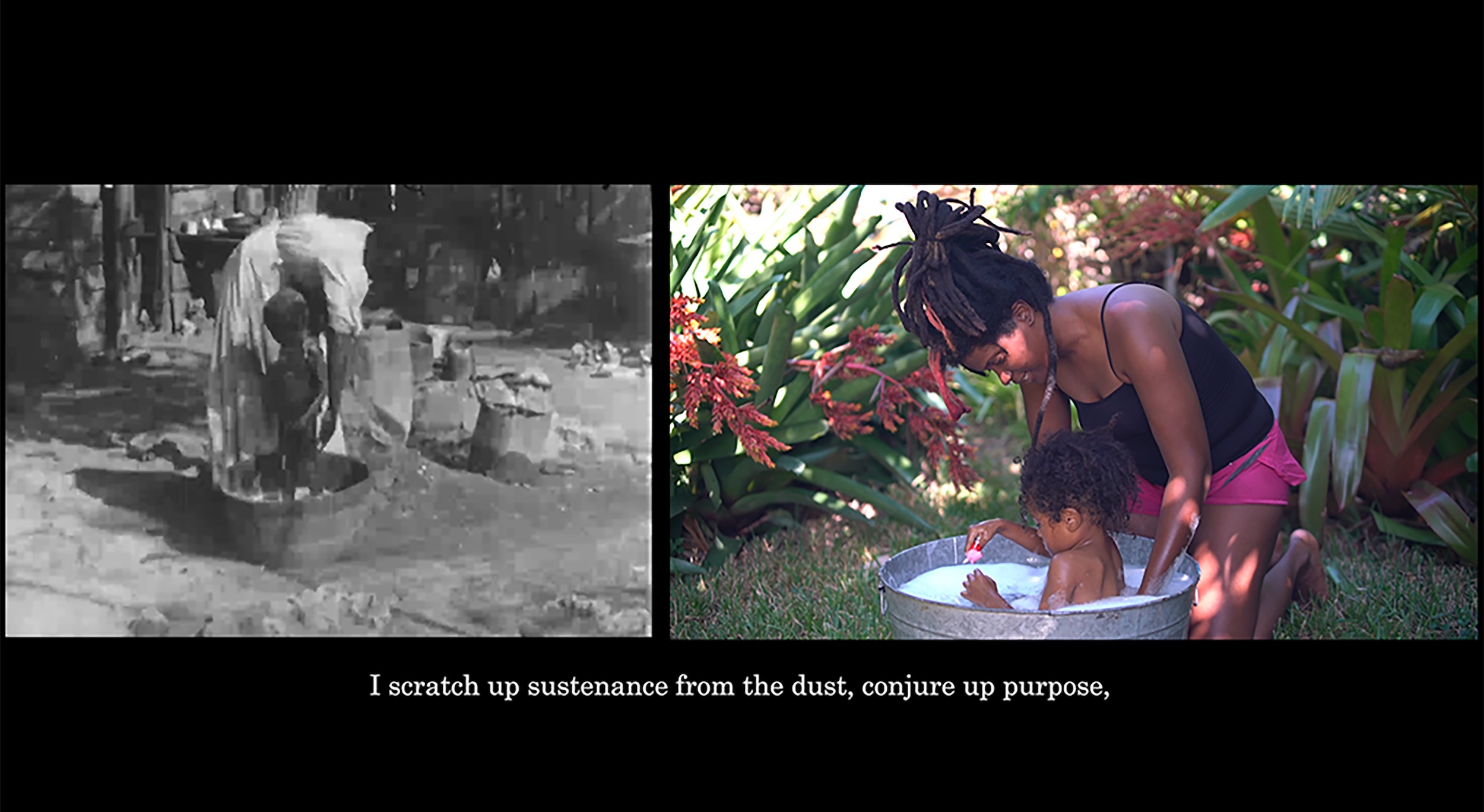

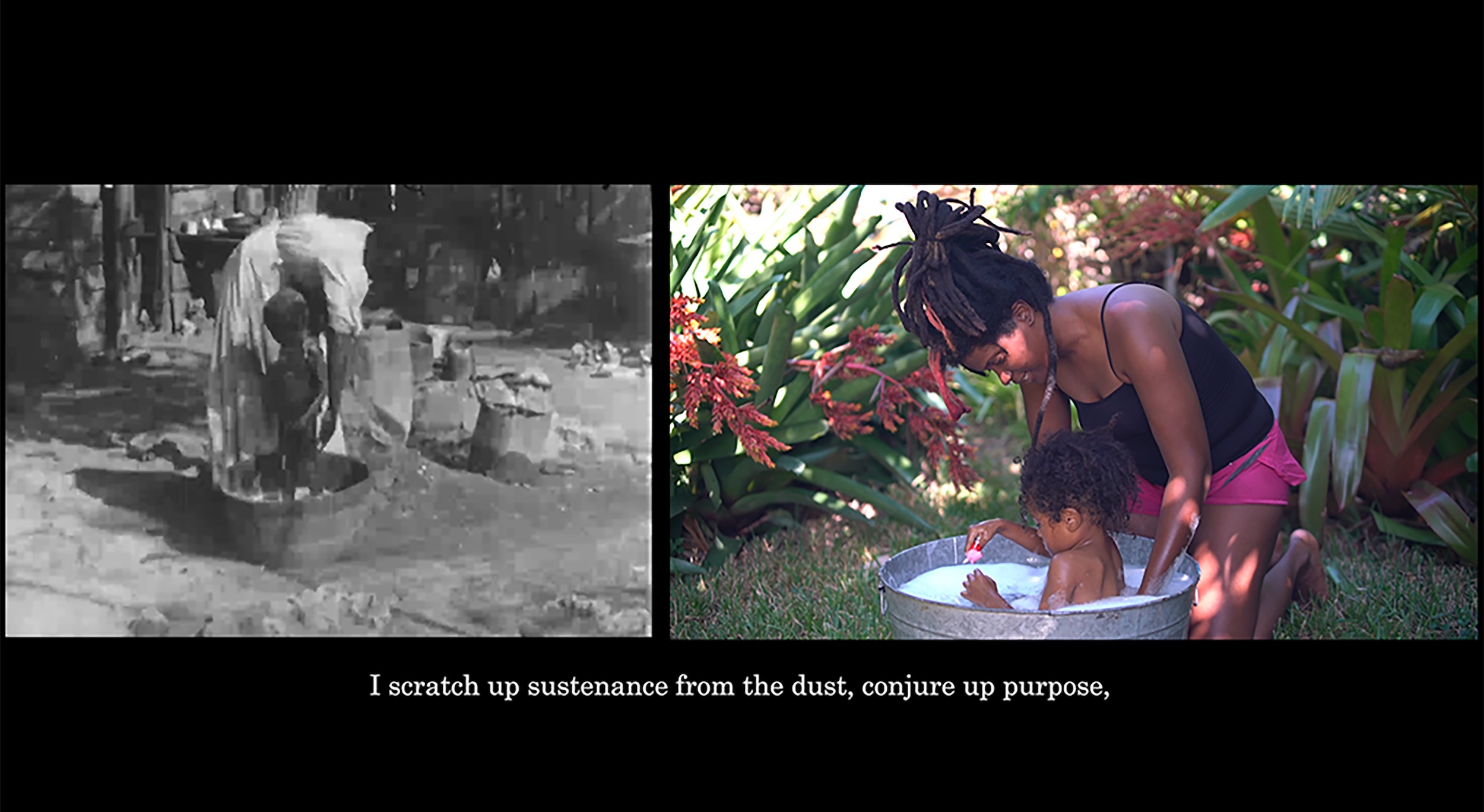

Artist, filmmaker, writer, researcher, and a fellow of the Library of Congress, Galanis keeps her focus on the way that the lens-based image shapes the Caribbean psyche. For her contribution to the “NE9: The Fruit and the Seed”, she draws together her skills in a multi-pronged approach to unpacking what our history means for Black Caribbean women. The film is silent, displaying archival footage (taken of the wider Caribbean between 1901-1903) simultaneously alongside Galanis’ contemporary responses. All the while, the words of Bahamian poet and author Patricia Glinton Meicholas run as caption beneath, doing just what captions do – providing key information into the meaning of the images above it. This is not illustration of poem, far from it, but the poetry weaving in and out of the struggles of Caribbean women, of Bahamian women, serve as the vantage point from which to begin to understand the work as a whole.

The eye darts between black and white footage of Caribbean women taken through the colonial lens, to the contemporary Caribbean women reclaiming spaces and denying gazes, to the poetry beneath giving words to the silent actors. But the silence here lays only in the archival footage, the women performing in Galanis’ modern interpretations do not need sound to make their voice heard. They confront with cutlass, cuss and ‘shoo’ the camera away from their tender bathing of their children, gyrate with a fixed eye on the viewer, and reclaim Nassau’s Parliament Square under the gaze of the statue of Queen Victoria in its slowly growing infamy and awareness in the public.

Parliament Square, that space that represents such an influential and ill-famed part of our history as regards to colonial and patriarchal power, is the backdrop for a West African spiritual cleansing of the space, by descendents of both those who have historically ruled this country and those who have suffered at the hands of them. Dressed in white and engaging in Yoruba tradition, the Ifa practitioners are a proud proclamation of the heritage of Black Womanhood in the Caribbean and wider Diaspora.

For Galanis, “Black women possess a truly indomitable spirit, since the beginning of time. We have been making ways out of no way, “scratching up sustenance from the dust” forever. Our movement toward a greater degree of self-determination continues to evolve even as the heat is turned up. Black women are out here risking it all for everyone everyday, this is a love letter to them, particularly to Bahamian women who have constantly relegated to subservience, even today, and especially through legislation.”

The gaze, and who holds it, is often symbolic of the social power held by certain demographics of people. It is the reason we feel uncomfortable when particular kinds of strangers stare at us in public, especially those who feel license to continue to stare at us long after we have already established eye contact to signal “I see you looking at me”. The Black feminist scholar and author bell hooks, in “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” breaks it down for us simply through the way we are taught to look (and not look) as children: “When thinking about Black female spectators, I remember being punished as a child for staring, for those hard intense direct looks children would give grown-ups, looks that were seen as confrontation, as gestures of resistance, challenges to authority. The “gaze” has always been political in my life. Imagine the terror felt by the child who has come to understand through repeated punishments that one’s gaze can be dangerous. The child who has learned so well to look the other way when necessary. Yet, when punished, the child is told by parents, “look at me when i talk to you.” Only, the child is afraid to look. Afraid to look, but fascinated by the gaze. There is power in looking.” (hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation, 1992)

We feel this discomfort too in the way men stare at women, the way minorities or people with disabilities are looked at, the way that we feel we have permission to stare at anyone who falls outside of some arbitrary-yet-inherently-political perceived “norm”. But the “norm” and what is considered “normal” is constructed, and it’s quite convoluted in its production in The Caribbean. The Caribbean norm must take into account the shaky foundation of old colonial behaviours – not limited to some quite toxic sexist, racist, and classist ideals. We must always hold in the forefront of our minds that which is European and African, but polluted by the exaggerated power structures of the colonial era. It is a gaze held in a time capsule that can be quite difficult to break out of. Living with your past in mind is one thing, and a rather important one for knowing where you come from. Living in the past serves no one and certainly not the strides for progress towards social equity that we have been striving for for the past couple hundred years at least.

Galanis takes women who historically had their personal and political space invaded, taking their discomfort and giving them new voice and agency through their modern-day ancestors who live through the evolved vestiges of that time. The way the film speaks through time, from great great great grandmothers to great great great granddaughters is one of the many ways she opens up the nuance of Black womanhood in the work. The work functions to begin a conversation between generations, to open that conversation up to different threads for us each to pull on and find our own path. And, surely, that openness to our individual experience within the collective is infinitely more valuable to the discourses of race, gender, and class that come up in the work, more than closing down avenues for meaning into one channel. The work functions the way blackness does, it doesn’t offer a singular or monolithic understanding, it has an openness to our felt nuance of experience.

The National Exhibition 9 “The Fruit and the Seed” is on view at the NAGB through March 31st, 2019 and supports the work of 38 Bahamian artists.