By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett.

According to the governor of the Central Bank of The Bahamas, John A. Rolle:

“The Concept of Orange Economy been around for 20 years. All sectors whose goods and services are based on [Intellectual Property], Architecture, Art… [this is the] [e]volving space of creativity. . . 4.3 trillion dollars [are spent in it] 2/12 times military expenditure”.

London, New York, Miami, all bring in millions a year from the Creative Industries. This is where the growth is in the economy; it is not in the imports that drain the cash from the national coffers. Shakespeare in Paradise is a tremendous example of the local Orange Economy. As the world advances into a service-oriented economy, where more people enjoy entertainment outside of their homes, or entertainment that they can access through the World Wide Web, we also stand to gain access to untapped markets. However, we, as the people of The Bahamas, have to be there. Currently, we are not. We hardly see the importance of creativity, or how it can and should be developed, promoted and protected. We do, though, as a nation, allow much of our resources to be squandered by international owners of industry and not by local owners of businesses. Theatre is one of the top attractions, along with cultural or heritage, and festival tourism. Cat Island, San Salvador and Crooked Island provide unique points for cultural and creative industries.

The Orange Economy or the Creative Industries are not new, yet we treat them as if they were untested and untried avenues to success. The former government often chatted about the importance of creativity, yet it promoted foreign-owned business taking advantage of locally-produced resources and talent. We can be the space of ingenuity and creation, but it is not usually produced by the systemic, ordered, or stymieing state-run space. Creativity usually happens in spaces that have socio-spatial permission to create, where individuality is recognised and promoted, not a dark, closed-in basement or corridor without collective gathering spaces.

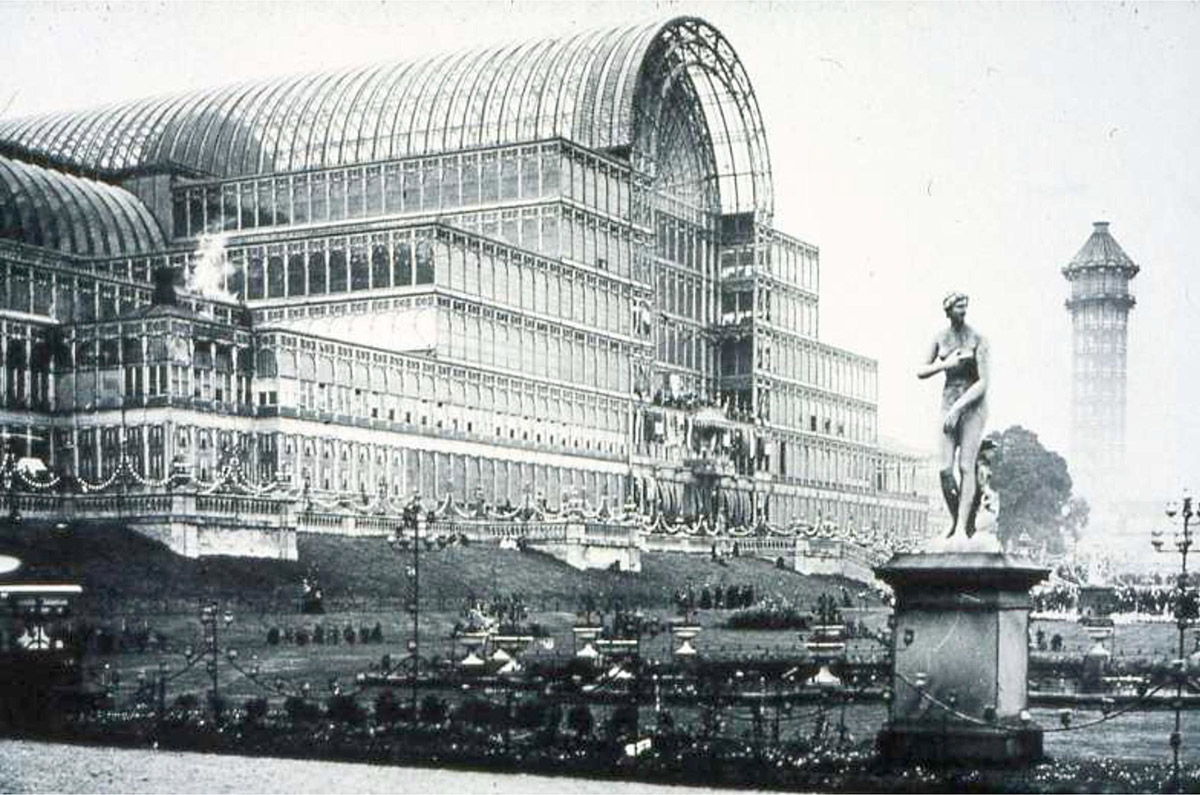

The Orange Economy Webinar produced by Creative Nassau in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank and the Central Bank of The Bahamas, took place on Wednesday 30th August brought together international presenters, their audiences and the local organisers, attendees and discussants. Image courtesy of Creative Nassau and Rosemary C. Hanna.

The Webinar produced by Creative Nassau in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank and the Central Bank of The Bahamas, at the Central Bank’s Training Room on Wednesday 30th August brought together international presenters, their audiences and the local organisers, attendees and discussants. Speakers included Felipe Buitrago Restrepo, from Colombia, Keith Nurse from Trinidad who currently lives in Barbados, and Peter Ives, from Santa Fe, New Mexico. All of the above partners have a stake in the local economy and in local creativity. Ironically, notwithstanding all the action and traction we get from these endeavours, the government as an institution remains, (in)agilely stuck in the late 19th-century early 20th-century mechanism of development through colonial visioning. As so many small economies like to look at Singapore as a model for change, it has to be said that their model is not an outdated, outmoded economic model that allowed people in government to continue to function as they did when we were all still controlled by external powers. Singapore reinvented itself, ridding itself of the dated ideas of governance. At the same time, it became somewhat of a police state.

Government seemed poised to support the arts and their development when the country was beginning its journey into Independence, but seems to have since pulled back. Support for Creative Industries is essential for development because there is a need for multi and plural vision and action or multiple levels of productivity in any country, especially a country that is as gifted to have such a rich and diversely talented population. Supporting the arts in the 70s the government was perhaps more focused on the productive genius of people like Winston Saunders, Clement Bethel, Edmund Moxey, because it saw the need for them and their incredible talent and ability. They were mined for what they could give the nation and in turn they gave more and more.

Another example of a visionary is H. G. Christie, land developer and founder of H.G. Christie Real Estate who sold land to foreign concerns, a great friend of Sir Harry Oakes, and a founder of The Chelsea Pottery, another institution that helped put The Bahamas on the creative maps. The Pottery once stood where the National Post-Office Building crumbles in the 21st century; and this is not political but factual. When our prized tourists venture off the cruise ships, much against the warnings from the floating hotels which bring them here, they leave with great trepidation.. If we look closely, we may see the shadows of a very interesting space that remains controlled by the past and shows no sign of moving into the future.

How then do we change this?

A creative centre could attract more tourists. As they emerge from ships, they would encounter art, music, food and agreeable surroundings, both, what can be referred to as, high and low culture. Straw work can be made publicly, as can real local woodwork, not cheap imported ‘Bahamian’ handcrafts.

Attendees Alistair Stevenson and Katrina Cartwright at The Orange Economy Webinar produced by Creative Nassau in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank and the Central Bank of The Bahamas. Image courtesy of Creative Nassau and Rosemary C. Hanna.

New Education

We need investment in education, but not the education of rote and rhyme, but the education of the future where we learn how to do things and how to empower our people. Why would employers from abroad not look to the country for employees and the next generation of thinkers, doers and creators? Perhaps they do, but we wash our hands of them before they even get to the point where they can be great at anything. This requires some unpacking.

Many extremely successful Bahamians have left the country early in life because they faced huge hurdles and great obstacles to their development, perhaps because they were not linear thinkers, perhaps because they were imaginary-visionary, had another kind of gift, had different ideas, they sought out other opportunities. For sure, The Bahamas produces great thinkers, but many of them leave. They become top thinkers and doers in world-renown spaces, but when asked to return, they are often stifled, and leave once more.

The Past and The future:

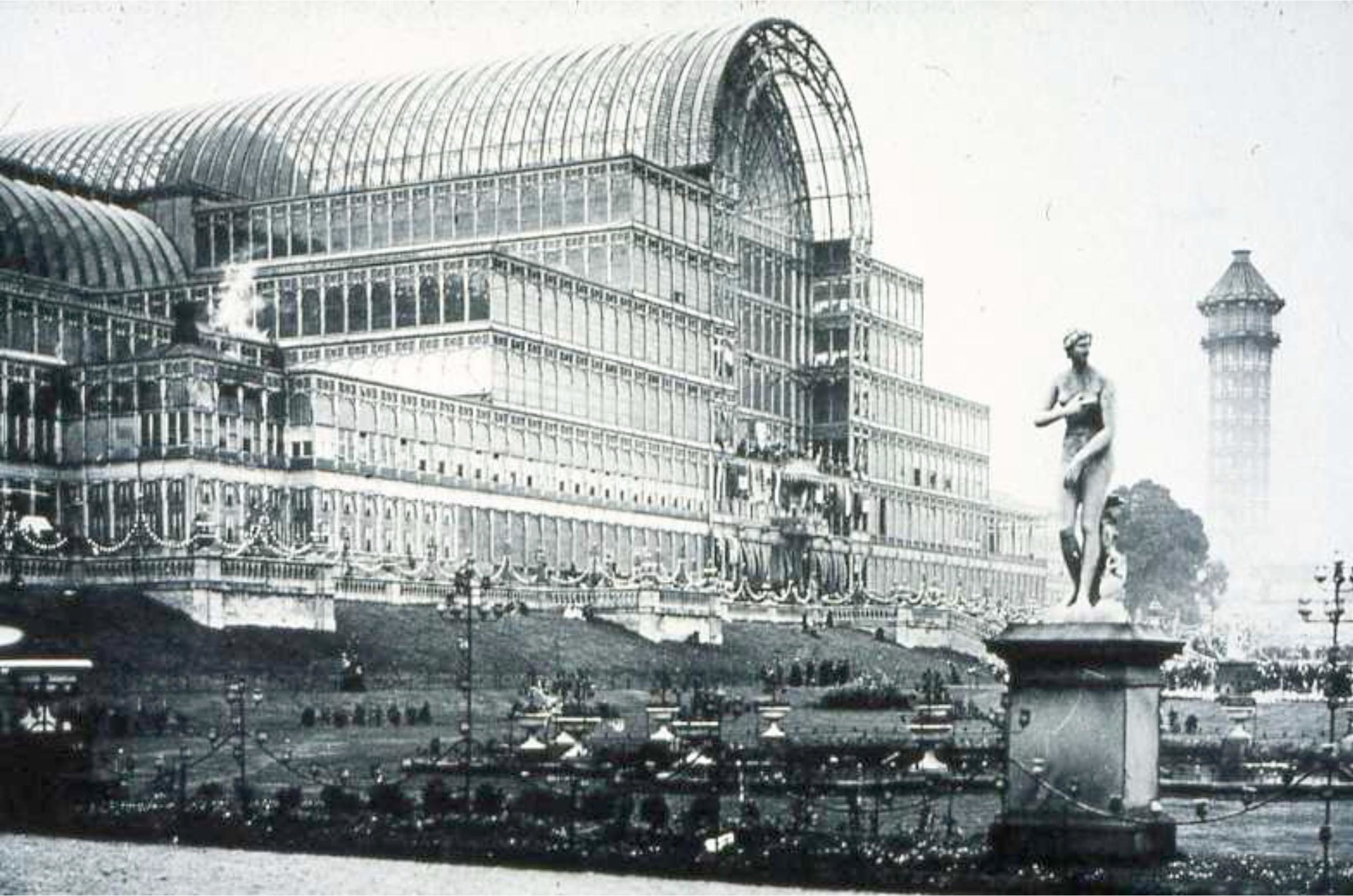

In the World’s Fair of 1851, the world was duly impressed by Britain’s ingenuity and design capacity when they unveiled the Crystal Palace, produced for the Great Exhibition of that year. Today, The Bahamas has the opportunity to use its ingenuity and creativity, design thinking and orange capacity to work towards the World Fair Expo 2020 to be held in Dubai, UAE. This is an opportunity unlike any other for the country to foreground the talent of the youth; it is not about old, established paradigms or models. We need new, and the new must be able to face the ‘new’ and shifting challenges of the new world reality, of which the floods and awful damages in Texas, USA are just a reminder or a sad, absolutely catastrophic example. Expo 2020 is a funded project to showcase Bahamian talent and youth and how The Bahamas holds promise for the future.

If we look to a local yet international development of changing paradigms we can use the example created at Albany in southwestern New Providence. A private community, Albany has created a new model, for The Bahamas, of high school education that promotes access to a world of opportunities. This offers a different type of space and time to what we see in local education, for the most part.

From a general standpoint, in a society like ours, heterotopias and heterochronies are structured and distributed in a relatively complex fashion.

First of all, there are heterotopias of indefinitely accumulating time, for example museums and libraries, Museums and libraries have become heterotopias in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit, whereas in the seventeenth century, even at the end of the century, museums and libraries were the expression of an individual choice. By contrast, the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity. The museum And the library are heterotopias that are proper to western culture of the nineteenth century. (Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias”, Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité October, 1984; (“Des Espace Autres,” March 1967, Translated from the French by Jay Miskowiec)

The Crystal Palace, London. The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and plate-glass building originally erected in Hyde Park, London, England, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Bahamas seems caught in the museum of out-dated models. Colonialism has left us with a lasting legacy that disallows a great deal of progress outside of formalistic processes which, in reality, stunts, retards and diminishes creativity, design and creative expression, and progress. In most schools and universities, like the new institution created by Albany, people come to find talent. Engineering schools at state-run institutions like The University of Puerto Rico are examples of this. Art and design programmes at the Royal College, small state-run schools, and small high schools, where teachers not only allow, but coax students to think outside the institutional box, not hem them into thinking that is limited and outmoded, those places with lawns, light, open windows and no barracks-like buildings, promote design and creativity that bring fame and recognition.

The University of The Bahamas could be the regional focal point for a programme and institute in Small Island Sustainability. It is important to think of the Creative Industries/Orange Economy as a productive way of seeing creativity, local culture and talent and removing the old constraints around professions set by traditional thought processes. We see that Modernism has given way to postmodernism, though modernism is still a thriving possibility for those who find its thinking and modes of expression useful; the advent of postmodernism did not kill modernism nor did it present its end.

Postmodernism as a multifaceted school of thought has allowed a different type of wealth accumulation and artistic expression that can no longer be easily challenged as being high or centre or in the margins. So, as much as postcolonialism has supposedly marked the end of colonialism, it in fact, has not. It can come after colonialism, but we also see now that while the time of colonialism may have ended officially, it was not ended really, rooted out and the thinking processes changed. Have we changed the way we view our creative industries, economy and potential to be a creative and sustainable hub in the region?