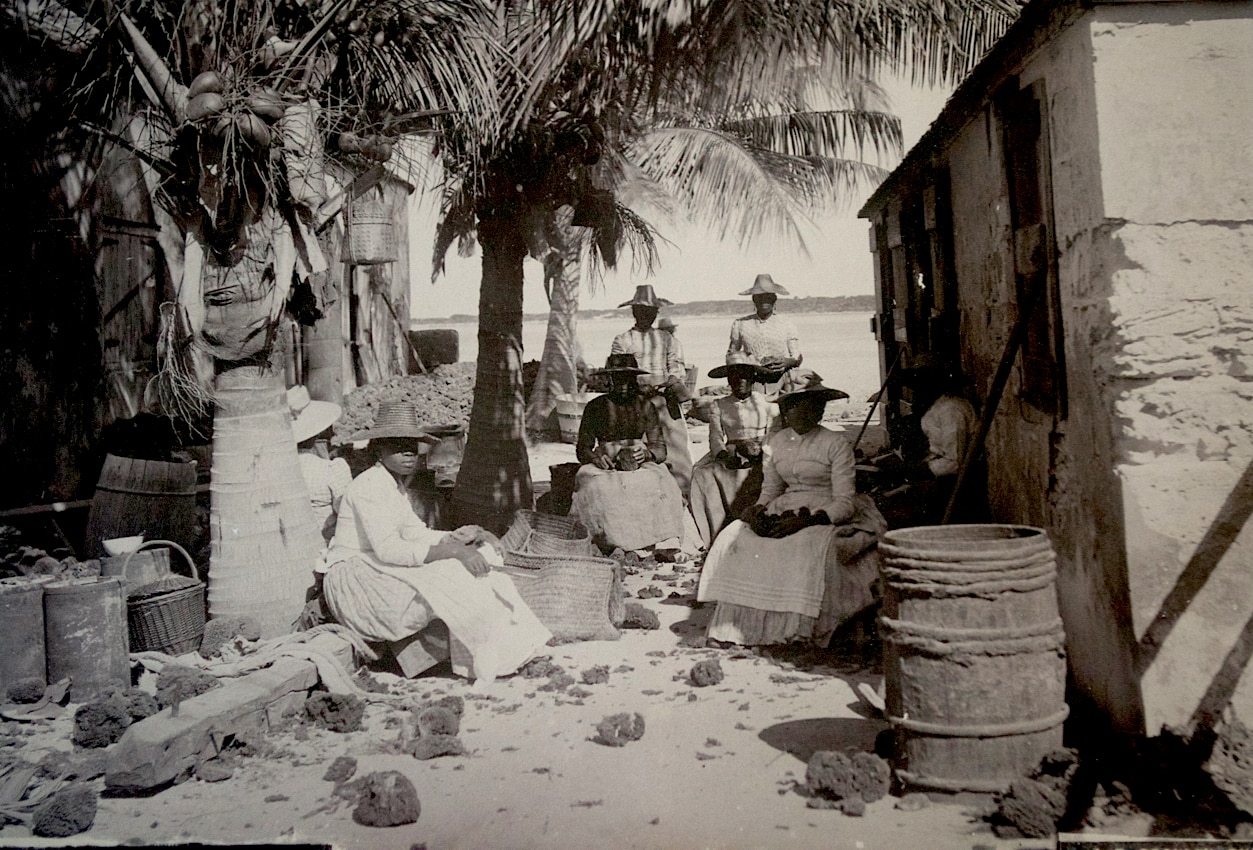

Scraped up from the beds. Uprooted. Carefully picked and collected. Transported by boat. Beaten. Sun-dried. Clipped and polished. Sold to the highest bidder. The sponge industry of the colonial Bahamas as represented in Jacob F. Coonley’s ‘The Sponge Yard’, an albumen print circa 1870, shows neat rows of sponges laid out to dry, to be clipped, to have the animal remains eroded away by hours in the sun.

Art of the Month ‘Sponge Yard’ by Jacob F Coonley. Albumen print ca.1870-1920.

The image itself is well-composed, with the rows all pointing to their source: the boats and sponge-fishermen blurred by their scurrying around during the industry at its peak. ‘Boom and bust’ is the story of most agricultural industries in our little nation, and sponging is no exception. In its heyday in the late 1800s and through the early 1900s, sponging provided employment to a majority of Androsian residents in addition to those in Long Island, Abaco, and the Exumas. There were over 600 vessels comprising the sponging fleet, carrying men to and from the sponge beds and taking the catch over to the Nassau Sponge Exchange to be sold.

Coonley, an American, who had a fairly successful career in photography in New York, moved over to work in The Bahamas in the 1870’s. His background in landscape painting is evidenced by the picturesque and alluring ways in which he frames his images – always charming, attractive, and aesthetically perhaps more about artistry in many instances than documentation sake.

As a region that was not only culturally shaped by the tourism-driven colonial photography of the 1800s, we were also physically shaped by it, as Krista Thompson elaborates in ‘An Eye For The Tropics’ (2006) and ‘Bahamian Visions: Photographs 1870-1920’ (2003). The landscape we know today was slowly tailored over years to fulfil expectations with the kapoks and poincianas that our well-to-do colonial visitors so craved. Idyllic images of the islands were sold thousands of miles away to lure visitors into our newly platformed idea of ‘paradise’, and so the image of The Bahamas was birthed.

No longer were we part of the ‘hellish’ and ‘uncivilised’ West Indies, replete with insects and diseases, considered a sort of living purgatory to those in Britain. The tropical representation we disseminated to combat this more negative prevailing image to our British colonisers soon became the very thing by which we came to know ourselves – and still identify with today. “All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.” So says the French theorist Guy Debord in his seminal text on the idea of the ‘Spectacle,’ outlining how modern life has declined from what is experienced into what is seen. This is something we know all too well from the meticulously manicured Instagram-lives we see being criticized and absorbed in equal measure, carefully curated to give the best portrayal of the polished life – whether the reality itself might not be quite so pristine.

However, can this idea of moving from existence to image be technically true to The Bahamas? As this region so shaped by the touristic image and this active re-framing of our representation, is it possible that have we moved as a nation into merely ‘appearing’ to be a paradise, or have we instead descended into becoming the perfect artificial picture we put forth? In a sense, perhaps we are performing our idea of Bahamianness based on a hundreds-year-old marketing effort pushed forth by our tourism industry.

Our ‘being’ and ‘appearing’, as Debord sees it, have perhaps become one and the same. Looking to Jacob Coonley’s albumen prints of the sponging industry helps provide us with both the carefully choreographed images of women trimming sponges, sitting up ‘proper’ and demure, being respectable black folks on the one hand. It shows that image of being acceptable and civilized and yet still exoticised, that tantalizingly tempting balance of the familiar and foreign.

‘A Sponge Yard, Trimming’ ca. 1870, Albumen print, Jacob F Coonley.

On the other side, with images like ‘Sponge Yard’, we see a more organic side to things, the ebb and flow of the industry’s movement at the docks where ships full of sponges flooded the mainland’s shoreline as much as the ubiquitous Victorian-era postcard images being staged, sold and exported. It feels lived, not acted. Tropicalization, the name for this process by which we manufactured our landscape, even our idea of ourselves put up for commodification and commerce, has irrefutably shaped our country and the region as much as our difficult pasts.

Our colonial governments and British and American corporations all played their hands in the production and circulation of this ideal, making good use of photographers like Coonley, William Henry Jackson, and even our own Bahamian James Osborne “Doc” Sands. Many contemporary cultural practitioners have since moved to resist this image, to help us try to uncover our truths, our sense of self and to rewrite our narrative as we know it. Coonley helps to give us a very specific iteration of our history, and his contemporaries in the Bahamas, now using digital lenses, are helping to give us representation of the multiplicity of our experience – away from the Facebook timeline photos of our sea-weed free beaches, sublime storms out on the water and heartbreakingly beautiful sunsets.

Instead, we also get the reality of the folks still living in ramshackle houses without running water – not made into quaint imaginings of the precious clapboard homes they used to be, but the paint peels and the houses slump and slouch like the backs of the toiling men and women who live within, striving to make that tourist dollar. We see more outside of the picturesque image because of artists like this and see the poverty instead of the quaint little houses. We see the ghettos and camps of illegal immigrants fleeing to places like The Bahamas that are nearby and seem safe instead of the hotels full of happy visitors.

Scraped up from their beds. Uprooted. Carefully picked and collected. Transported by boat. Beaten. Sun-dried. Clipped and polished. Sold to the highest bidder. Eerily familiar?

We are more than the clipped and polished image of ourselves. We are a nation framed by our experiences, by our rises and declines. We are individuals, but collectively bearing the weight of history’s residue in our cultural memory as well as the newness of the everyday. We carry this two-faced sense of self, and it is a feat often overlooked. In looking at these photos it becomes a sober reminder that we are more than our image, we are lived experiences, we are bodies tossed and turned by the tides of life, but we are just that – alive, not just an image.

This photograph and more work by Jacob F. Coonley can be seen in the NAGB’s permanent exhibition, ‘From Columbus to Junkanoo’ co-curated by Jodi Minnis and Averia Wright through Spring 2017.