By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett.

Bahamian history and memory are often trumped by the Empire and the identity it imposed on its subjects. Last month marked the 70th anniversary of India’s independence from Britain, most of which was negotiated by Lord Mountbatten, the second cousin of Queen Elizabeth II, who was sadly killed by an Irish Republican Army bomb. These are facts independent of his role in negotiating the end of British imperial presence in India, but at the same time, the establishment of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and an Independent India during a troubling period called ‘Partition’. In August 1947, when, after 300 years in India, the British left, they left a deeply divided and fractured country. Independence was one positive, but the legacy of Empire and the lasting impact of colonialism were deeply felt. Imperialism and colonialism have divided great swaths of land, usually from under the very people who inhabited those spaces.

In other words, the invention of tradition was a practice very much used by authorities as an instrument of rule in mass societies when the bonds of small social units like village and family were dissolving and authorities needed to find other ways of connecting a large number of people to each other. The invention of tradition is a method for using collective memory selectively by manipulating certain bits of the national past, suppressing others, elevating still others in an entirely functional way. Thus memory is not necessarily authentic, but rather useful. (Edward Said “Invention, Memory, and Place” Critical Inquiry Vol.26, No 2 (Winter 2000) p. 179)

The pain and loss, or torture and gain of independence and partition are concisely discussed in The New Yorker (2015) by William Dalrymple. The nationalist project in fractured post-colonial states is alive and well in defining how we see our traditions. It is interesting that, as Said points out, the small and unified communities began to disappear through the island to capital or rural to urban migration, we see the creation of a unified Bahamian tradition that attempts to erase the individuality of all the island communities and their unique experiences. Usually, we are cast under a deeply problematic Victorian shadow that never allowed individual identity, but insisted on a strict moral code that continued to exclude non-whites. E.M Forster’s A Passage to India so splendidly captures the shadows.

“A Sisal Plantation” (ca. 1857-1904), Jacob Frank Coonley, albumen print, 7 x 8. Part of the National Collection, originally owned by R. Brent Malone.

Much like the partition of India into Bangladesh and Pakistan as it received its independence from Britain, the territories went on to live through decades of violence and tradition making that justified and promoted further ethnic and religious violence. Postcolonial nations are built on a feeling of loss and trauma without understanding why because so little is discussed. The idea is to silence opposition to and awareness of the events. Both BBC and Al Jazeera provide excellent histories of the partition and the independence event. However, the former seems to eclipse the latter, but they create an interesting if not comfortable coexistence of countries that were once regions governed under the Crown.

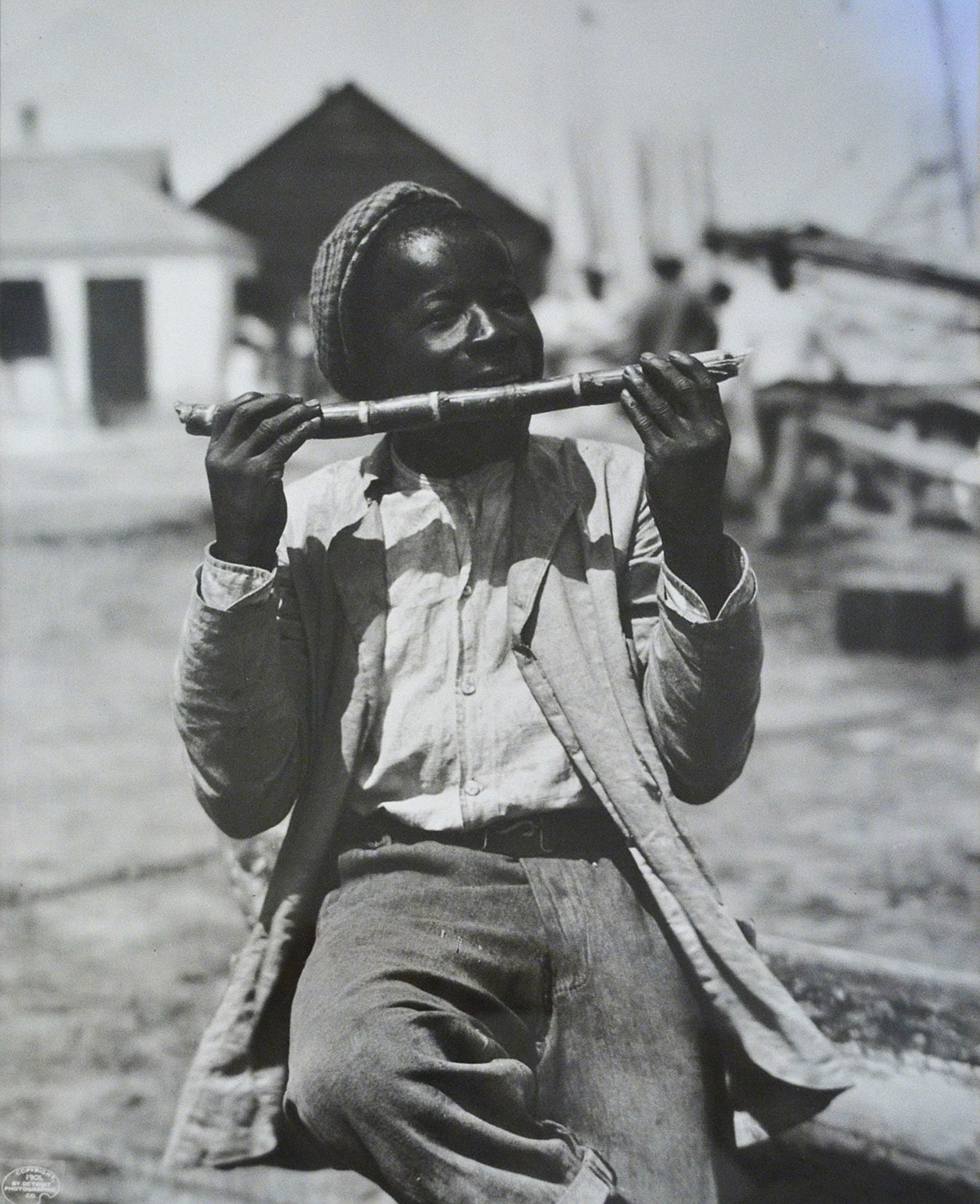

It must also be remembered that colonization was not about being a benevolent and loving patron of a people but a company ready and happy to extract all the wealth it can from the space it sets up shop in. Such was the case in India, where the Royal East India company began business as a private trading company. The BBC has provided excellent coverage of this before it becomes a ‘national’ interest. It must also be remembered that tradition was formed or create India, and that was the creation of tea, of hunting, of spices but also of controlled savagery or an interesting term from Homi Bhabha ‘Sly civility’. Without India, Africa and the colonies in the Pacific, there would be no tea, something that has become so quintessentially British. Many of the images that we still identify with because we understand that it was better in the old days are imposed or created traditions, such as sugarcane processing. There would not have been sugarcane here albeit on a small scale compared to the other (former) colonies; the photo of the ‘Native Sugar Mill’ is a tradition imposed on the space by colonization, imperialism and slavery.

As the two outlived the latter, it is not unthinkable that the impact of the former will be that much more in depth in the psyche of people. The trauma of living under the whip and of facing unjust laws that made one less than human in what would be considered one’s place of origin speak loudly to this reality. Living in the shadow of Empire is in great part all of that. The images of civilised colonial tropical living as presented from the gaze of colonial history would always entrap one’s ability to be. There would be no tea without British colonisation, as much as there is far more coffee in the rest of the Caribbean islands colonised by Spain is instructive of a past that has never ended and has continued to inform the traditions of today.

While it is important to understand and remember the reality of the past, as bell hooks notes, living in the margin as a site of resistance, not as a site of limitation, as so many colonisers may consider it to be. In The Bahamas, the margin created by segregation has all but vanished, though the legacy and the weight of the segregation and the demarcation of space has not. In fact, the weight of the margin and the marginalisation of particular groups who inhabit those areas once seen as exclusively black is now even more pronounced. Though we no longer see it as racialised, in fact, the class and race of it go hand in hand. The racialization is far more nuanced and subtle as was evidenced in 2016 with the Paradise Beach Protest that was dismissed because it was carried out by a group of violent young black males who could not ‘manage themselves and so needed to be treated violently as the photos on the front page of the Tribune attest.

Fast forward to the protest over the fire at the one time Harold Road dump, now known euphemistically as the landfill, earlier this year during the IDB conference at a yet unopened Baha Mar, where the scathing criticism of light-skinned and white people who could obviously not be from here. These vestiges of knowing one’s place deeply entrenched and long lasting from colonialism and imperialism allow people to be othered in very interesting and disturbing ways. Both criticisms challenged the group’s’ national belonging, of not knowing their place and of being out of order.

These are huge legacies of colonialism that we do not see or hear because they have been normalised by the shadow of oppression. It is not coincidental that most of the population will not understand how to challenge the discourse that posits them as non-nationalistic when they try to speak up for themselves. This is when the common space and spatial justice is denied to people. While many will not notice this subtly deployed message of social control and order, it is clear: light-skinned people are non-nationalist and black people are violent and disorderly, all threaten the national fabric of the country; all must be controlled. We know better than they. The superior attitude of those who rule through ascent, and legacy, but who have never thrown off the colonial vestiges.

We do not understand the weight of history and the legacy of imperialism. It is clear that most do not know or have never read Bahamian history where control was maintained through seriously destructive and divisive laws and policies like the Vagrancy Act, and “A Modified Form of Slavery: The Credit and Truck Systems in The Bahamas in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” as Howard Johnson notes.

History and its knowledge are essential to a real sense of self. It is also necessary for a population to be able to read and write, count and think in a manner befitting of citizens, not subjects. When names of historical landmarks are changed, and spaces shifted, land sold off and erased, burial sites excavated and living memory erased, we become a history less place and people.

“Native Sugar Mill” (ca. 1901), William Henry Jackson, Original glass plate print on archival paper, 11 x 14. Part of the National Collection.

Said states it well when he writes about the erasure ofPalestine for the creation of Israel.

“These territories were renamed Judea and Samaria; they were onomastically transformed from “Palestinian” to “Jewish” territory, and settlements-whose object from the beginning had been nothing less than the transformation of the landscape by the forcible introduction of European-style mass housing with neither precedent nor basis in the local topography-gradually spread all over the Palestinian areas, starkly challenging the natural and human setting with rude Jewish-only segregations. In my opinion, these settlements, whose number included a huge ring of fortress like housing projects around the city of Jerusalem, were intended visibly to illustrate Israeli power, additions to the gentle landscape that signified aggression, not accommodation and acculturation”. (Said, p. 189)

The shadows are very dark spaces where it is extremely difficult to become one’s self. The shadows always cover any individuality and identity that does not fit with the imperial project. Art continues to provide an excellent window into the past, in the shadow and what imperialism and colonialism looked like in the Caribbean or so often called the West Indies. It is also interesting to note that those who were intricately involved in the creation of the new India through partition, with the influence of Lord Mountbatten who is also so much involved in the early development of Bahamian land, as he and many of the Royals received handsome land grants, to which we still pin our identities. Eleuthera and Harbour Island are spaces specifically spatialised in this way because of their history of settlement. This resonates with what Catherine Palmer (1994) sees as tourism in The Bahamas depending so much on colonialism and its landmarks. When land grants were handed out, and as the special on Slavery produced by the BBC underscores boldly after slavery ended those slave owners who suffered loss were handsomely compensated for their losses. They gained exponentially through a change in the law that never ended the impact or the shadow of slavery. When the policies and laws remain rather similar or unchanged more than one hundred years after emancipation, how can we truly believe that we do not inhabit the shadows of Empire?

India and Pakistan, as well as Bangladesh now exist as independent countries, but their spatial identity and their social occupation of those spaces now rest heavily in the aftermath of partition and the violence it imposed. The creation of independent countries and identities is fabulous, but the legacy of violence and distrust is even deeper, heavier and more long-lasting. Here I quote from Dalrymple’s story where he cites a book by Nisid Hajari: “Nisid Hajari ends his book by pointing out that the rivalry between India and Pakistan “is getting more, rather than less, dangerous: the two countries’ nuclear arsenals are growing, militant groups are becoming more capable, and rabid media outlets on both sides are shrinking the scope for moderate voices.” Further, the power of nostalgia to block the possibility of true post-colonialism is amazing.

When nostalgia rules the day and England or some parts thereof still think of the colonies as quaint places where uncivilised plebeians remain and should be civilised, and this is a glorious moment for us to retake our position of leadership, then we understand that Empire holds tightly clenched fists around the potential for development free of its shadows. Dalrymple states it thus:

[T]he current picture is not encouraging. In Delhi, a hard-line right-wing government rejects dialogue with Islamabad. Both countries find themselves more vulnerable than ever to religious extremism. In a sense, 1947 has yet to come to an end.

Shadows are usually dark and frightening places/spaces of deep-seated fears, insecurities, anger, hatreds and often trauma. The shadows seem to be poised to consume all potential, unless and until we can deconstruct the legacy and remove the lack of speaking across foreign-created boundaries and barriers that have scarred peoples and places for millennia.