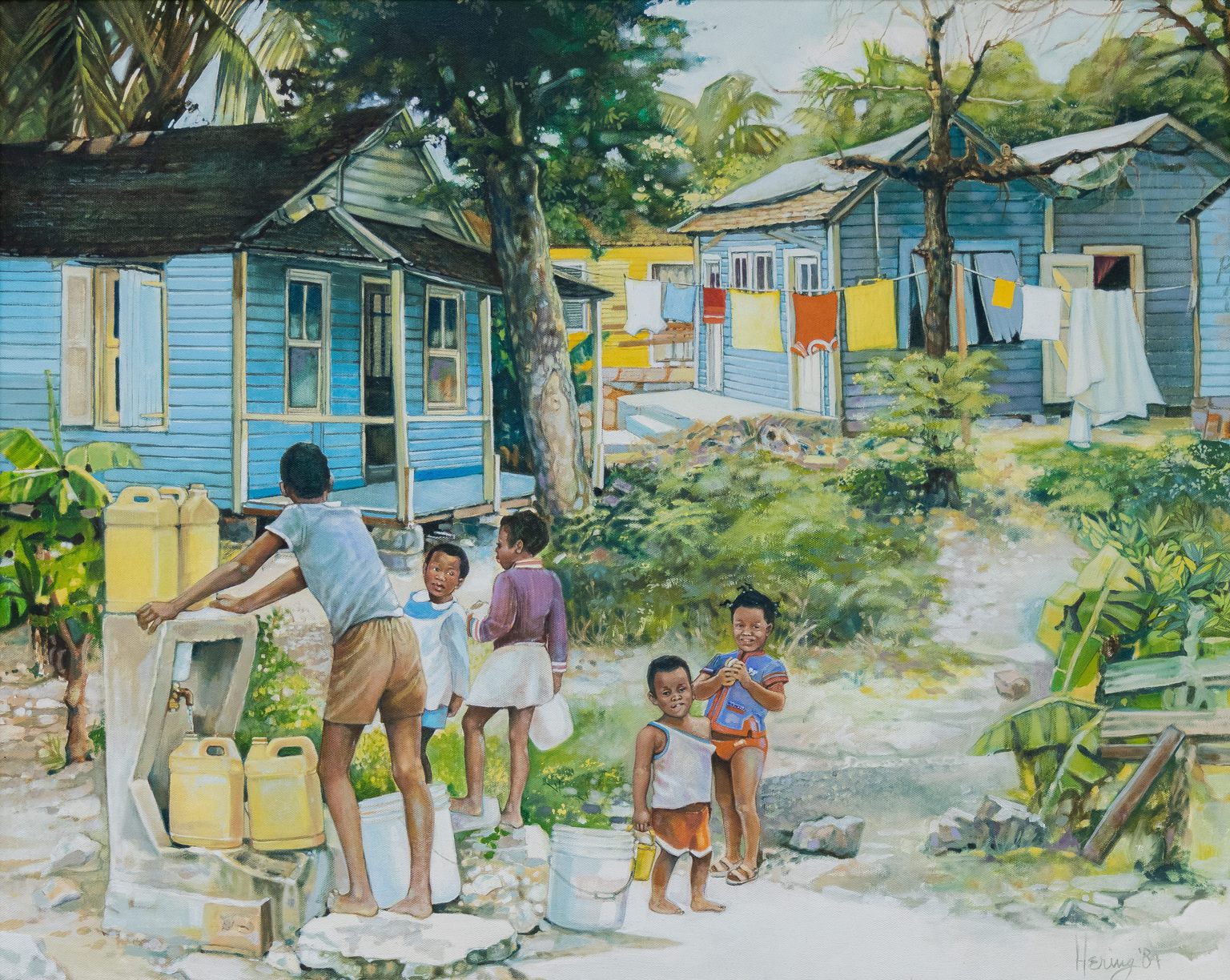

Little ones on a dusty road of varying ages – tiny hands held in those only slightly bigger, leading the way, wearing boots too big for one so young. Plastic jugs and containers stacked up, some half-empty and some half-full as water gushes forth from the spout. Peggy Herring’s ‘Five Children At A Water Pump’ (1984), a deftly executed oil painting on canvas, is our November ‘Art of the Month’ here at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB). It is currently on show as part of our permanent exhibition, ‘From Columbus To Junkanoo’ curated by Jodi Minnis and Averia Wright, and a very telling part of the National Collection (NC) when you start to look more closely at it – figuratively speaking.

Detail of “Five Children at Water Pump” (1984), Peggy Herring. Part of the National Collection. Courtesy of the NAGB.

‘Five Children At A Water Pump’ is quite a quaint depiction of the life of so many Nassuvians. Beautiful clapboard houses, which clearly could do with some subsidy for renovation, and no running water within that house. The image of someone walking down the street with a shopping trolley full of a myriad of different water containers: gallon jugs, 5-gallon containers, buckets, the whole lot, it’s ingrained in our consciousness as a part of the everyday here.

The painting is bright, both in color choice and in the quality of light shown. For all intents and purposes, it would appear to be quite a cheerful image. However, the way it has been curated, alongside Jackson Petit’s ‘The Home We Share’ (2015), turns the work into a piece of social commentary. Why? There is a thirty-year gap between the two paintings and yet the image is the same: no running water in these houses.

Perhaps the piece wasn’t intended to speak to the issue in this regard, it certainly wouldn’t appear so, with how pleasantly the picturesque scene has been rendered. It’s certainly enjoyable to look at and gives off more of an idea of ‘look at the adorable children playing around the water,’ rather than ‘why are they still pumping water in the 80s?’. This is what makes the painting function in such an interesting way: it is through its comparison with Petit’s work, produced 3 decades afterward, that the conversation opens up.

This is the way that good curation often works and why it is so vitally important. It elevates work to new levels by opening up different dialogues that might not previously have been considered, simply by the ‘conversations’ between the works placed beside each other. It is a visual language in its own way, a language of signs and certain combinations will unlock new ways of understanding and ‘reading’ a work, as can be seen here.

Both paintings are undeniably beautiful in their own ways, and we are not unfamiliar with seeing the ‘everyday’ for Bahamians elevated—whether it’s attempts like Herring’s and Petit’s–to show a certain joy and strength in the struggle and how commonplace it is, how it seems ‘default’ to us. Or, in a more perverse way, the manner in which impoverished peoples the world over (ourselves often included) are pictured to incite pity amongst the wealthier, more Western audiences – particularly as we come up to Christmastime, sometimes seen as ‘harvest’ season for charities. However, despite the fact that these images both seem intended to uplift in their own way, it is again this dire thirty-year period with no change that makes them feel considerably less cheerful.

“Five Children at Street Water Pump” (1984), Peggy Herring, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Part of the National Collection gifted from the FINCO Collection.

Of course Nassau is an old city, one that grew quite organically for most of its life, many of the houses are antique and have seen better days, and of course we understand that it becomes a logistical nightmare to uproot streets and floors to install plumbing – but isn’t it one we should want to suffer through, knowing that the quality of life will be so improved afterward? The school groups coming to the gallery are always amazed on tours when they hear that nothing has happened in all that time. You see the gears turning in their heads when they realize that even though ‘this is just how things are’ and ‘this is how things have always been’, that it isn’t quite right and isn’t how things should be.

The imagery of yard chickens that we see in other works is certainly more endearing, as that is a considerably more sustainable part of island life – but pumping water to live, or even buying water as many of us do, is simply not sustainable and says a lot for how we function as a country. We can afford to assist with infrastructure for mega-resorts and the like, but we cannot put forth mandates that call for these hotels, as part of their agreements to be here, to assist with plumbing for the average Bahamian? We can ship over tons of water from Andros, or set up expensive reverse-osmosis plants, but still can’t fix things thirty years later to help the family over the hill, who see cruise ships in and out every day and tourists down Bay Street being looked after and seen to, unknowingly to them, above the citizens that reside here.

Art has the capacity to help us interpret and archive our stories in ways that are wholly different to historic record, but retain the richness of the humanity inherent in all our experiences. It is accessible. It is honest and it is telling, even where it is not intending to do so at the time of its making.