By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

So much of our lives is defined by our relationship with space and indeed with water, or a space that is not a space, but is actively always churning and redefining itself and its boundaries. We engage at a new level now as boundaries mean little, except for the new and ever-increasing global boundaries that allow capital flow but insist on barring the flow of people. We live in a time of shifting and yet unchanging spaces. The space of the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the Florida Purchase (1819), the Spanish American War that ended in 1898 and the conquest of New Mexico, Texas, Baja California and those spaces that were once Spanish Land, in these we see the complexity of space. Yet, as island dwellers, we are always defined by water.

Our identities are always reified by water and the barrier it creates to relating. In a ‘radical’ book from the 1980s “This Bridge Called my Back,” a group of ‘radical’ women of colour got together and articulated what, until then, had been assumed off limits to them; their voice, their identity, their cross-border and interstitial existence. Yet we seem to have forgotten these women who would have made life somewhat uncomfortable for some because of their insistence on being seen and heard, on being citizens and women, and in fact on being women of colour with rights at a time when there was little if any space in feminism for anyone who was not status quo.

The borderlands that their backs cross are important because they are once again being redrawn. We islanders, though, have always had liquid or viscous relationships with space. Today, this relationship is changing as many governments develop no tolerance, hard-line politics against anyone who is “not like me”, or better put the politics of exclusions. These politics go as far as to reinscribe, describe and ascribe meaning to those who are uprooted by hurricanes. Those who can no longer afford insurance or who will no longer be able to live where they have lived for generations. They are being phased out. We have suddenly walked into a new age of deglobalisation in a global world where people should know their places and identities must be contained, controlled and managed.

In film and art, photography and painting, the frame determines so much of what we understand. The montage of scenes also directs how we make meaning as compared to the flow through a scene. The barriers are returning to the frame and what we are seeing is not necessarily all that is there. Water, in our temporal and spatial plain, though, isolates or connects, and right now, we are using it as a tool of isolation and boundary protection, notwithstanding its porosity.

Immigrants go home! Migrants leave! Mexicans are dangerous! Blacks are untrustworthy! Tourism is our saviour!

Joiri Minaya. Installation “Invitation To Transgress” made from spandex, 10 x 26’, on view as a part of the 6th Double Dutch, entitled “Re: Encounter,” on view at that National Art Gallery of The Bahamas through Sunday, November 26th, 2017.

As we begin to recover from the displacement brought home through Irma and Maria, powerful hurricanes that have obliterated many Caribbean peoples and dwellings, we look at the mise-en-scène in the newly opened 6th incarnation of “Double Dutch: Re: Encounter,” that opened at The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas on October 13th, 2017 which reveals a great deal of light displaced by darkness and the interstitial space between life and art, between me and not me, and between the fence and the wall.

As we live through what is rapidly becoming an exclusionary time, where walls are being erected to separate, fences are used to make good neighbours, and gunboat diplomacy seems to be making an active return to the stage, we are being annexed into various camps that preclude discussion or even understanding. Walls can be physical separations that serve to protect or metaphorical divides, invisible to the eye, but brutally implicated on the psyche. There is no crossing these invisible but tangible divides. Perhaps they are best called visceral reactions to divide. Today, we talk about cutting off people’s family ties through the creation of exclusionary national spaces. But what happens when the space is created without a nation, deeply denationalised, deconstructing the very physical space that we imbue with identity politics? Perhaps we have come to a heterotopia. The island getaway is a utopia. Foucault in “Of Other Space: Utopias and Heterotopias” (1984) states:

First, there are the utopias. Utopias are sites with no real place. They are sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case, these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces. (p. 3)

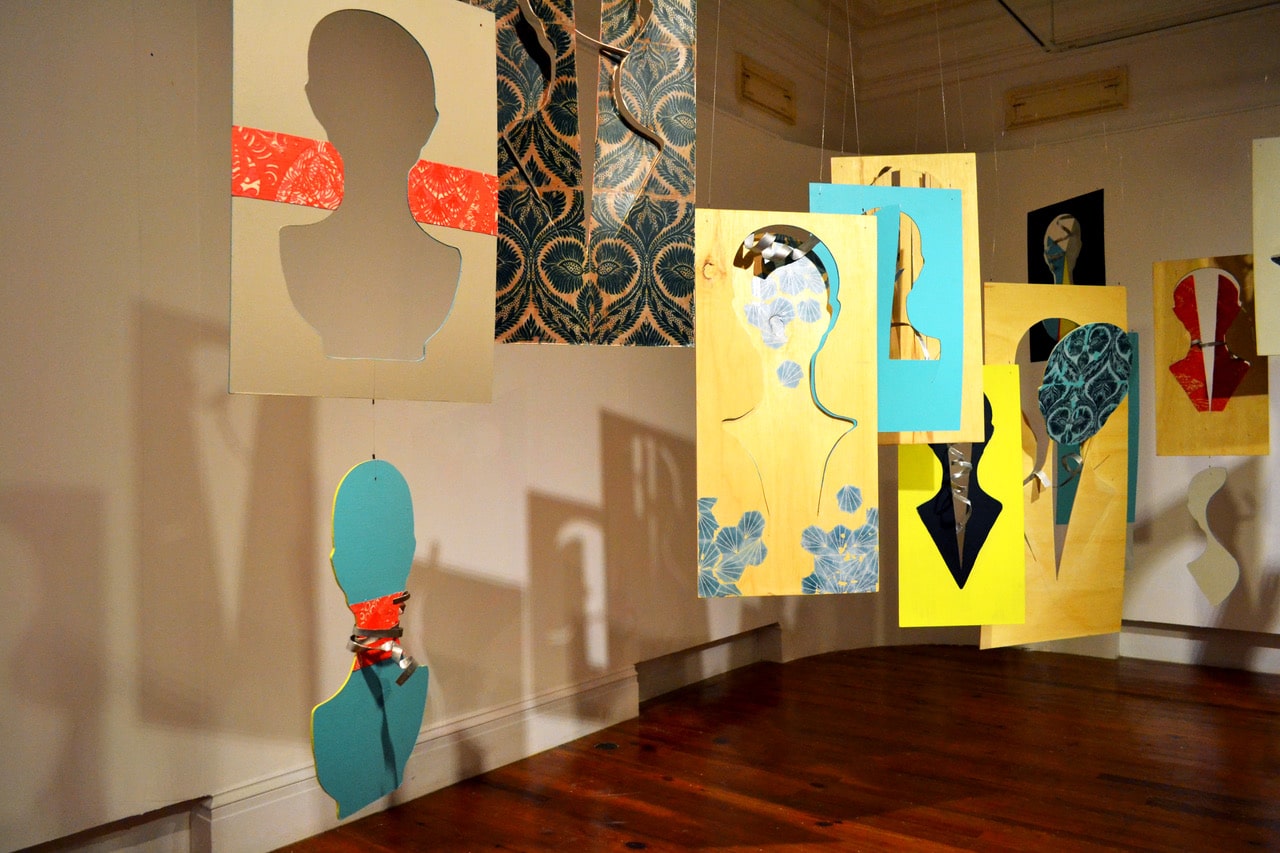

We often create spaces that we see as utopias; these are today defined as cruise ships, and desert islands, where only a few people live in luxurious splendiferous. Dede Brown and Joiri Minaya bring together two rather distinct artistic praxis on a kaleidoscope of overlapping meanings that seem so simple and un-disturbing, so pretty and usually so quaint as to not bother, some pretty things hanging, a little material separation that provides spaces to move through, stretching and flexible but nonetheless present, bounding and framing.

These two women stage an intriguing tropical adventure, without a great deal of danger because all the danger has been removed. The pretty textures are only disturbed by the hard surfaces they inhabit, cover, hide. As Minaya works through the viscosity, the porosity of the liquid body of water and the interstitial serration of space through fencing and deep separation, she speaks of isolation and loss, but not a loss of which we speak or are even aware. In her work the serration is obvious.

Dede Brown. “Tessellations (Pieces of You, Pieces of Me).” Installation on view as a part of the 6th Double Dutch, entitled “Re: Encounter,” on view at that National Art Gallery of The Bahamas through Sunday, November 26th, 2017.

In Brown’s work, there is no serration, the bodies all flow. In the path of Minaya’s cruise ship, we see a wake, so gentle we can hardly believe it can inflict pain. It brings pestilence much as Iago poured it into the ear of the Moor or Hamlet’s gravedigger wished it on Yorick for madness. Pestilence is in daily use.

The works as constructed by Minaya and Brown disturb the discourse by showing what is often not seen. We can peel back the layers and reveal devastation, division and distrust. We live lives deeply tropicalised by the very divisive nature that asks if we own cars in the Caribbean. Are we given to the poisoning of too many Iagos?

As the border wall goes up and little rocket man is thwarted by spatially-racially-ethnically-sexually divisive discourse, the world of art has to make sense of the discontinuous nature of the deeply de-globalised world of neoliberal distrust. Minaya’s film “Labadee” presents the mise-en-scene that can so easily hide the guts, either through the obvious flow or the montage of discordant images. This work, though so light and playful is so powerful and demanding of our attention. It challenges the apparent norm of depoliticised utopias of cruise ships and desert island getaways where only the few can go, and there they can be serviced by those who have no access, though their bodies are strewn in the wake of the cruise ship. A submarine link to a middle passage gone but never forgotten, to a migration that only a fool or desperate human would take arms against, that enriches citizens through the exploitation of poor souls who political history has been so unkind to.

The tragedy of history is usually that we never undo its poisonous power much as is obviated when Edwidge Danticat writes, “They treat Haitians like dogs in The Bahamas”. (“Children of the Sea,” (1995) p. 15)

The “Double Dutch, Re: Encounter” on display currently, bothers this understanding as we pick up the pieces of our lives, it is ironic or poignant that we are complicit in our demise. As Danticat continues: “To them, we are not human. Even though their music sounds like ours. Their people look like ours. Even though we had the same African fathers who probably crossed these same seas together.”

If we go further into this exploration of the serration of boundaries that make happy neighbours, the disavowal that allows exploitation and the bridges or backs of those who have spoken up to change the way we perceive power inequities, we understand that we are only welcome today. Tomorrow the barrier may rise higher. But the higher you built your barriers, the taller I become. As the interstitial space becomes a poison elixir to separation, these works of framing silence and disparity, articulating disempowerment and exploitation the lovelier the art becomes.

I cannot think of any more fitting work and a more appropriate time to pay a kind of reverence to the life and work of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Do we need to rethink the Bahama purchase that seems to be a part of the Louisiana and the Florida purchases of the 19th century? Are we simply disappearing into the mise-en-scene without a voice as we deracinate, much like hurricanes do and serrate the spaces between us? Meanwhile, we are beguiled into a placid money making existence where walls need only be metaphorical for now, but barriers are truly inflexible as long as we allow them to be.