By Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

The University of The Bahamas

Our culture is as much about how we build, live and die, as how we speak, dress and eat, and George Cox, for me, embodied one of those shapers of Bahamian vernacular culture, simultaneously impacting high culture. How we live is as important as what we do and both influence the legacies we leave.

As I child, having spent much time with my grandmother and her siblings, I met and got to know many of the people who were well above my age and rank. Conversations were always fascinating and diverse. When George Cox died last month, it brought back memories of those times, before all those people would have passed on. Although not of my grandmother’s generation, Pearl Cox and my grandmother shared a love for flowers and gardening and would show their skills at the then Carver Garden Club flower shows. Those days are long gone, but the creativity and innovation in design are cross-generational.

The vernacular in the built environment

George Cox became and remains an icon in Bahamian culture, designing and overseeing numerous buildings as an engineer of considerable repute. He had a keen eye for working buildings into the landscape of place and fostering functionality in the space. Each building, as small and ‘insignificant’ as it may seem, speaks to a particular aspect of Bahamian life and culture. Many homes and older public buildings were constructed with wrap around porches, windows with shutters that could be pulled-in, to close the house off from direct sunlight in the heat of the day, and shared spaces, usually in the front of the house, where passersby would stop and chat

If we observe on Spanish Wells, for instance, people still embody that style of close interaction where porches encourage conversation. This is a part of the Bahamian vernacular, and in so many ways George Cox’s work flowed with this kind of specific simplicity and cultural nuance that allows buildings to function as an extension of nature.

The eye of the observer

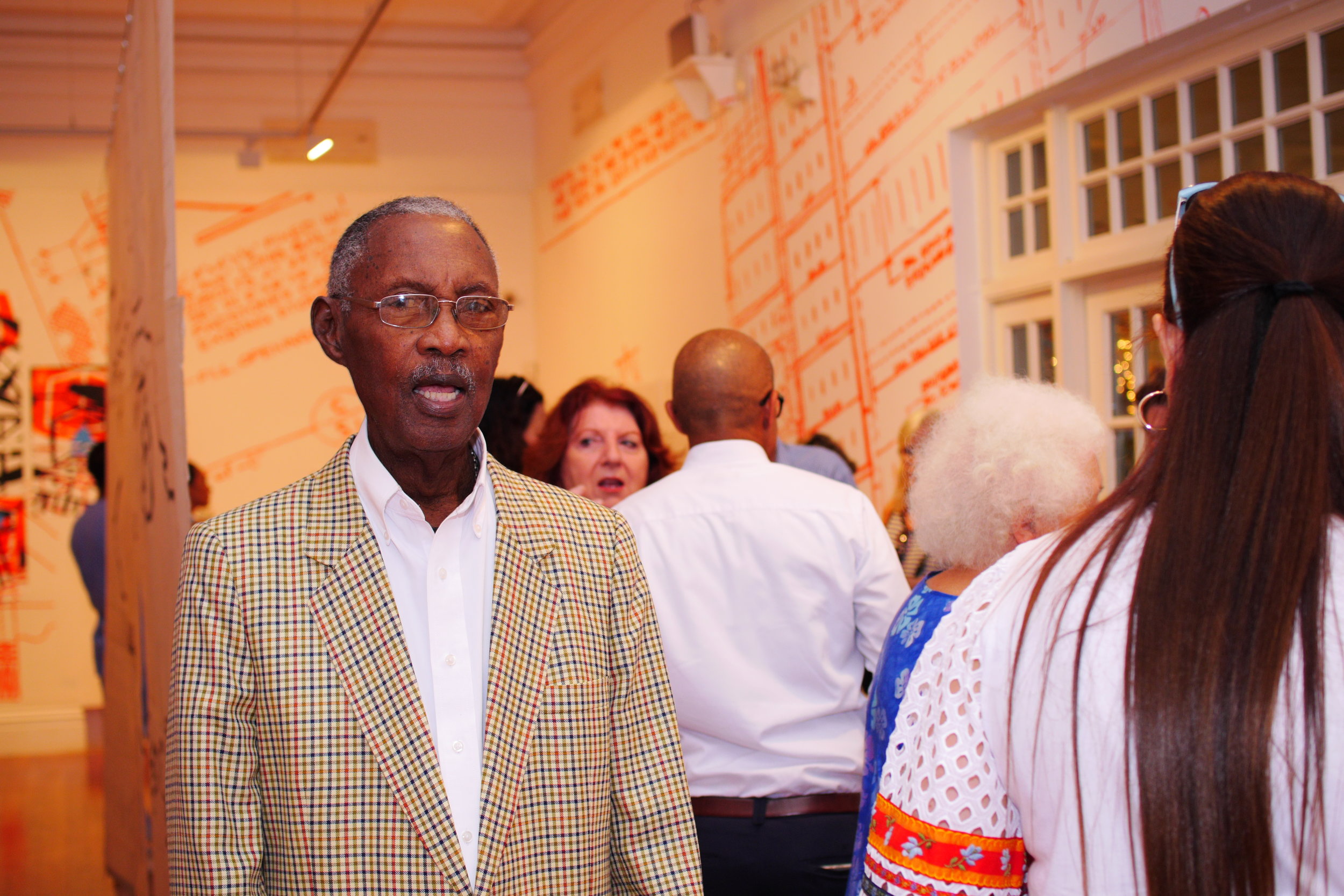

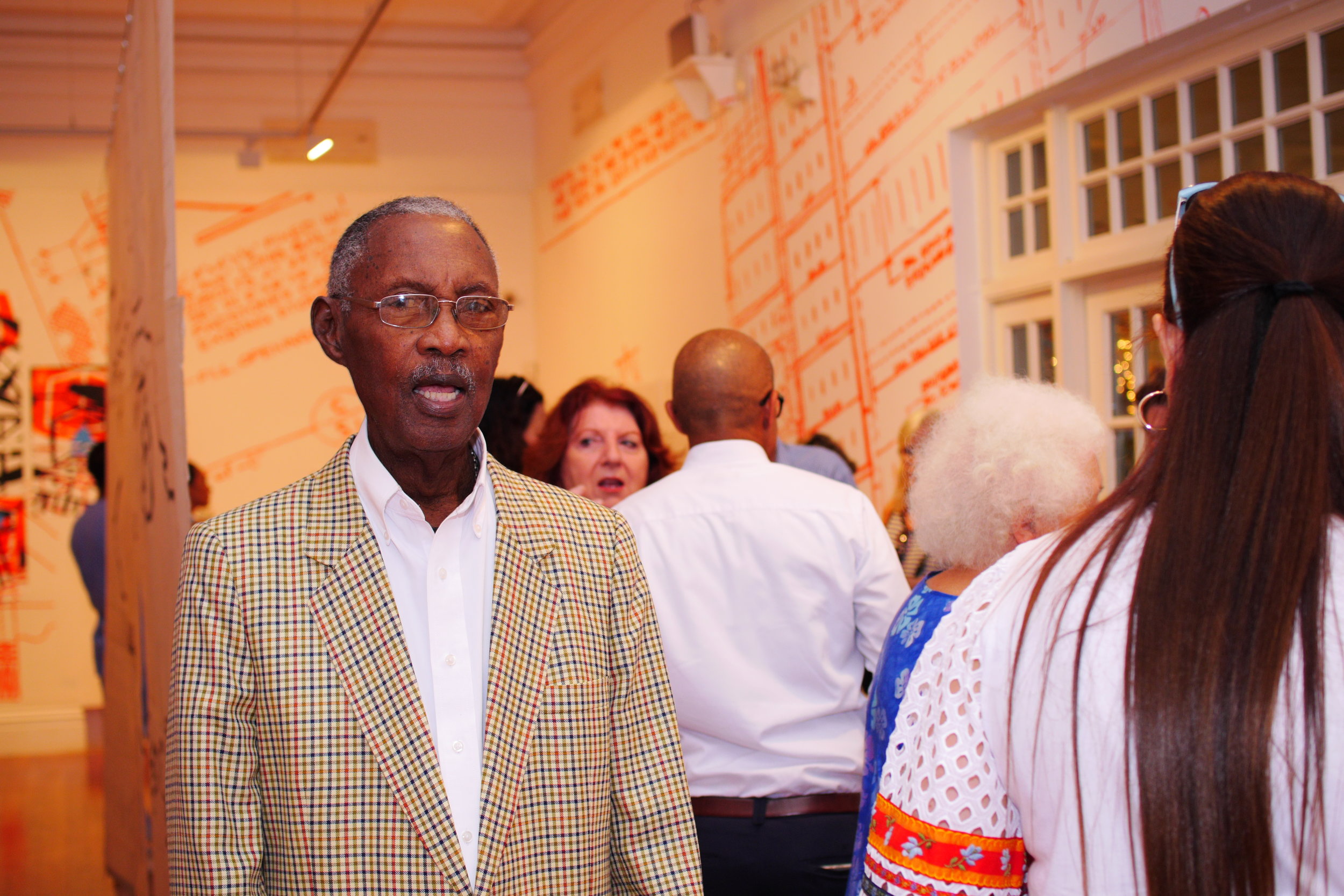

The project here is not to remember all the many significant achievements but more to discuss how George Cox–a massive yet gentle and kind soul– brought the combination of culture and space into his work. He produced many great buildings, and like Jackson Burnside demonstrated an acute awareness for what could work in this environment, and how to bring both inside out and outside in, as one can see so clearly in the new church at St Anselm’s in Fox Hill as well as the restoration project of Villa Doyle that now houses The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. Once again all of this speaks to the Bahamian vernacular as spaces flow into each other and the surrounding landscape. To be sure, as houses change and become more stylized to an outsider’s gaze or standards that do not gel with the local environment, we also lose the gardens of old, where food was grown, and livestock reared.

While some people may have reservations about the NAGB inhabiting this building, we have to consider the importance of space in historical retrospect. If we are to merely demolish history because it creates discomfort, then we come to a place where the lack of tangible history allows a people to become a drift on a sea of nothingness, which is almost where we are. I see George Cox as being one of those designers of space in a Bahamian vernacular who worked against odds through segregation and majority rule, without any apparent animosity, but who succeeded in spite of many encumbrances that may keep others back today.

In the olden days, people did not talk about change agents or all these words we use today; one got on with the work one did, especially given the challenging social environment of the time. It becomes apparent to me that the further we move from independence, the less it means for the young generation and the meaninglessness of ideas of that struggle and strife to them. The importance of physical space and its relationship to place and environment have also melded into the background as we prefer to erect buildings that bare little, if any relationship with this place, but rather import an ethos from other environs and cultures. George Cox built in a style that worked to highlight the space he inhabited–an open and bright space–that blends the structure and materialism of Church with the sanctuary of green and the tranquillity of courtyards and porches.

Living Nationalism

Some people talk about nationalism and others live it; they create the direction of the nation through things they do and how they live. George Cox was one of these individuals who worked to design a national ethos in the built environment. Cox brought this awareness of lived experience into his practice and vision; he shared this widely with those around him. As we grow, we must develop a sense of self that hinges on who we are, how we live at home and in ourselves.

The famed divide of colour, race, and politics apparently insurmountable an age ago, was transcended at Cox’s funeral. Although Cox has created a lasting impression on Bahamian vernacular and design culture it is also his incredible generosity and kindness of spirit that shows the actual impact on our time and people.

Though Dylan Thomas may have penned:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light. (1951)

George Cox went gently, but also un-gently as his legacy stands testament. As a nation, we are living in the dying light of erasure. Should this be raged against? It is when we look to gentle pioneers of design like Cox, we can understand a better way, and sit in awesome wonder of how much Geroge Cox has influenced another generation of designers and thinkers. Perhaps his impact on the built environment will transcend our knack for destroying history and culture and yet another building.