Reporting From Rome: The Care in Curating

By Natalie Willis.

Three weeks of Italian summer and being surrounded by art professionals sounds like a dream, and in many ways, of course, it is. From the “shallow” things—like eating gelato for breakfast (which, I’ll have you know, is entirely civilised)—to the deeper stuff, of discussing intense readings around the purpose and history of curatorial practice and being able to view Caravaggio paintings in resplendent old buildings, the Goldsmiths ‘Curating The Contemporary’ summer art intensive, hosted at the British School at Rome, was an education, and in ways I had not anticipated. I was supported by the Charitable Arts Foundation as well as The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas to embark on this journey of professional development that would prove to also be one of intense personal development.

We were a troupe of 17 delegates all from different stages of our careers (some only just considering embarking on a curatorial practice after finishing Fine Arts studies, some long established) and we were also from considerably different backgrounds – all, however, were women. There was a large European base of participants (from Poland, Denmark, Germany and quite a few UK citizens), but also a few American women (who ranged from recent graduates to Whitney and Guggenheim employees). There was also a contingent of us from the peripheries of the world, including myself, a Portuguese director of an institution in Macau, and a Columbian university lecturer. This was, no doubt, a way to try to ensure a diversity of experience and opinion as we went through discussions on the best practices of curators, what curatorial practice is, what it should do, and the difficult political history of ‘the museum’ as an institution.

Inside the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (National Gallery of Modern Art) in Rome, Italy. One of the sites investigated on the Curating The Contemporary course run by Goldsmiths (part of the University of London) hosted at the British School at Rome.

Perhaps, at this point, it might be apropos to explain just what exactly curating is. The course has problematized the way I feel that I can best elucidate it, but while that aspect might be difficult it has, however, made clear to me what I feel my role as a curator is and should be. Simply put, curators are often exhibition-makers (though that is now often used as a term in itself, hence my problem) as well as the caretakers of collections. This means that the role of a curator can span anything from cleaning and arranging the care of a damaged work, to installing artwork in an exhibition, to working out the logistics for shipping out work, to researching artworks and coming up with the theoretical framework to ground an exhibition. It should become obvious, then, that curators are Jacks- and Janes-of-all-trades wrapped into one.

For myself, the most important part of being a curator is knowing how best to support the arts ‘ecology’ and environment in which you work. Supporting artists, letting the work lead, is all part of it. To curate comes from the latin word ‘curare’ which means ‘to care.’ Many of us have lost our care and have put ourselves in a position of irrefutable power, to the detriment of ourselves and the community of artists and people we serve – and more still, some of us forget that we cannot and should not speak for people whose experiences we know nothing of. Support is meant to be the order of the day here.

Outside the British School at Rome in Italy, the research space that served as our host for the two-and-a-half-week course in Rome on curating.

It may be quite curt to say, but I find myself quite disillusioned with the institutionalisation of art – from the indoctrination into what ‘counts’ as art that we receive in university to the way that certain institutions become validators of what is ‘good’ contemporary work. Even people themselves become a sort of institution, or biennales become an institution and ‘tastemaker’ for work. Don’t get me wrong; I had brilliant tutors at a small university who cared deeply enough about my experience and potential to give me what tools I needed to make up my mind about my position in the world and therefore my position within the art world. However, even they are subject to the pressures of academia and how to prepare students for life outside of the cushioned (albeit perpetually broke) life of university. They delivered to me the information about art theory and practice that is so rooted in problematic ideals of the Western art world, with not just a heavy pinch of salt, but full-on seasoning that would satisfy any Bahamian. They didn’t just tell us that “Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida are important” but also that “Foucault and Derrida have great ideas but are entirely inaccessible to the larger public and what does that do for us? Who does that serve?” For that, I will be forever grateful. They had, at least, sparked that seed of doubting who and what counts as important, allowing me to make up my mind about what was important to me and so many other people like me.

Outside the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna. ‘ARS’ is the Latin for ‘art’.

In many ways, visiting the Venice Biennale at the end of my trip helped further to crystallise this. The pomp and glamour of the almost 200-year-old art event – one of the biggest for the art world – seemed to me akin to playing dress-up. That is particularly facetious to say, of course, but there was in the main grounds of the Biennale this feeling of trying too hard that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. This was not my first time at the Venice Biennale, my first experience had been in 2011 as part of a university trip, and the whole thing changed my life and view of art forever. But while nostalgia and my ignorance at the time might be bathing it in a rosy glow, there was something that happened there that I did not feel this time.

Maybe this is ‘growing up’ in the art world, but something was missing and something felt forced, that is until I left the main grounds to view the smaller independent pavilions throughout the city. Mongolia, for example, had a small pavilion that was entirely funded by the artists (whereas most national pavilions are at least in part government-funded, and the politics inherent within this becomes apparent), and it showed. It lacked the sleek, polished finish that the main spaces had and it had an honesty in its articulation that shone through.

“I cannot create as a curator.” Beatrix Ruf, a German curator and the current director of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, said this to us during one of the many talks we had with a number of curators from different stages in their career. Ruf is quite renowned and for good reason. She is an absolute force of a woman and at the heart of her curatorial practice is the artwork and the audience. She spoke of not being able to “create” because for her the role of a curator is to see what is there in the world and to highlight it – which, ironically, sounds like how many view art practices now, and I certainly do. She pushed the idea of not turning artwork into ‘documents’ that illustrate our ideas as curators; she stressed the importance of not silencing work.

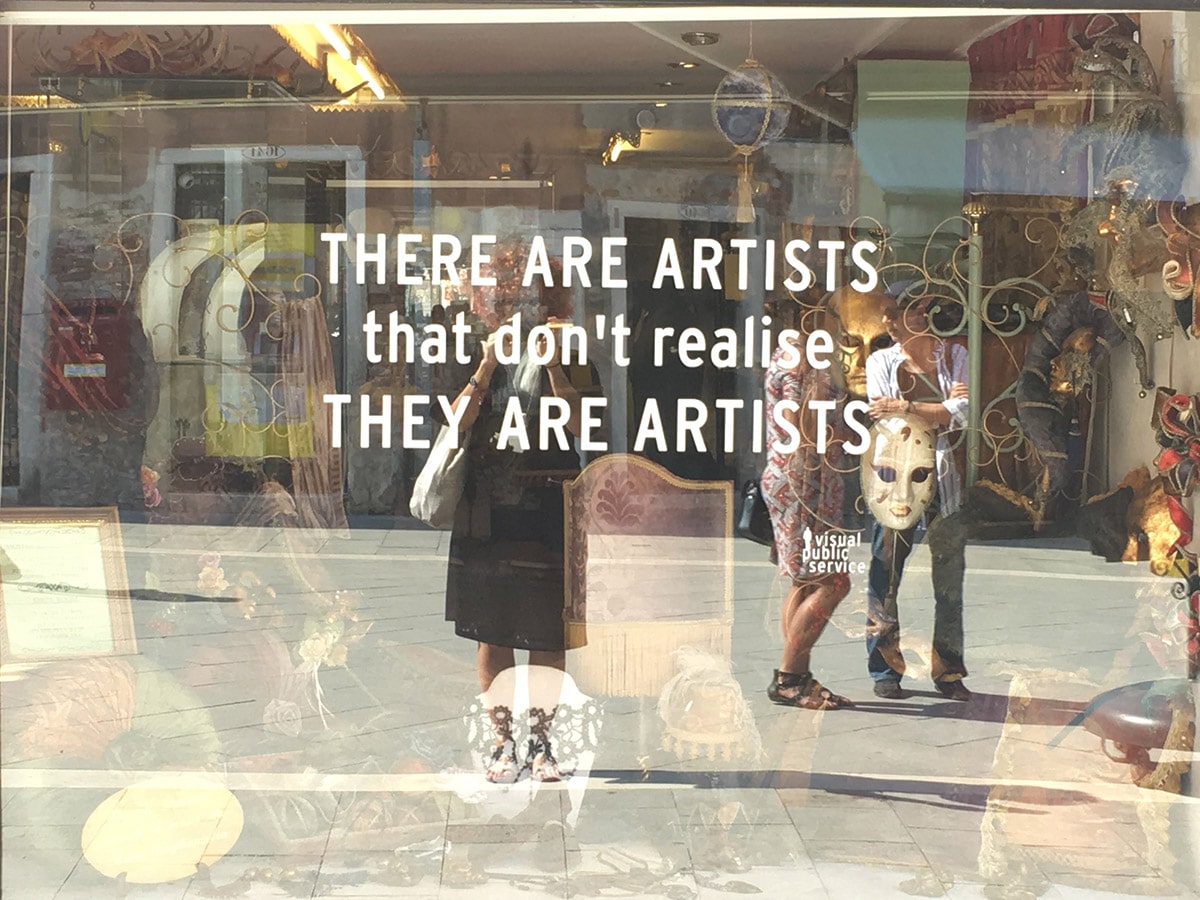

A shop front in Venice that was used as part of the Venice Biennale 2017 public artworks.

“You can always trust your audience.” The Mongolia pavilion certainly did. Ruf was adamant that no matter how experimental an exhibition or work is, quality always comes through to people. Adding to this, I would argue that honesty always comes through to people. Trust is what we need to make any art environment thrive and it is something that many feel the art world is lacking.

The content of the discussions and readings were stimulating and I don’t believe I will ever be able to live amongst a more eloquent and empathetic group of people in such large number again. However, what I learned most from this course, from this journey I dare say, was through my introspection and the treading of a difficult line as someone who is both of European descent and who is Other, existing outside of that Europeanness. I have gained more in insight than any book could give. My personal conclusions at the end of this course: I know myself and my ethics in working in more acute detail than ever before; the art world is struggling under the weight of its own difficult and dominant Western, Eurocentric history; and lastly, the care in curating is still there – we just may need to look South to find it.