By Dr Ian Bethell Bennett

Tie a black piece of cotton around the child’s wrist, Don’t walk outside at night without covering the child’s head, Be careful how you come into the house at night, Wipe your feet off well. Cover the mirrors with cloth, Open the house if the coffin comes by, let the spirit travel through, Rosemary helps keep away bad-minded things…

To our mind, these are all local lore. To many, these are discredited as they are lumped together with Obeah and dismissed as ‘evil, black, Dark and African.’ Our double-consciousness denies the survival or the importance of such cultural elements as Asue, Lodges, Burial Societies, Friendly Societies, all of which allowed our spiritual and physical survival during and after slavery.

Pure spirituality is being smashed by an all consuming globalization of ideas and cultures that over washes all uniqueness, but perhaps this too is temporary, as Kirkley C. Sands intimates in his book on Early Bahamian Slave Spirituality: The Genesis of Cultural Identity (2008). While Patricia Glinton-Meicholas’ An Evening in Guanima: A Treasury of Folktales from The Bahamas (1994), for example, illustrates some aspects of Bahamian lore and spirituality, there has been no significant project work done on Bahamian spirituality, perhaps because it crosscuts so much of Bahamian life and creative expression, though we do not see it.

The way we combine herbs, make teas, cure illnesses, is all predicated on understanding spiritual health and balance. Our observance of the moon cycles, though pagan, is also spiritual. We embrace Christmas more as a pagan holiday than as a spiritual celebration often that is eclipsed by Easter and its solemn importance to Christianity. Many refuse to see the deeply spiritual side of Catholicism or Christianity, though the celebration of death is similar in both. Why fear what is inevitable? Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5:4, “Blessed are those who mourn for they will be comforted.” As we lose a great part of our cultural identity and heritage, we see the words of José Martí:

“The prideful villager thinks his hometown contains the whole world, and as long as he can stay on as mayor or humiliate the rival who stole his sweetheart or watch his nest egg accumulating in its strongbox he believes the universe to be in good order, unaware of the giants in seven-league boots who can crush him underfoot or the battling comets in the heavens that go through the air devouring the sleeping worlds. Whatever is left of that sleepy hometown in America must awaken. These are not times for going to bed in a sleeping cap, but rather, like Juan de Castellanos’ men, with our weapons for a pillow, weapons of the mind, which vanquish all others. Trenches of ideas are worth more than trenches of stone.” Nuestra America, (1891).

In ‘Nuestra América’, or ‘Our America,’ Martí posits the spiritual mixing of our people in the Americas. It is the fusion, the syncretic combining of North and South, Europe, America and Africa that has brought about this incredibly spiritual existence, this ability to ‘sit with the bones’¹ as recent transplant, Canadian/Bahamian scholar and artist, Charlotte Henay puts it.

Tony McKay a.k.a Exuma. “The Stars (Signs of the Zodiac), oil on Canvas, no date. McKay’s work will be featured in the upcoming exhibition “Medium: Practices and Routes of Spirituality and Mysticism” on view at the NAGB from December 14th. Image courtesy of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation

Yet, as Bahamians, we seem to be walking away from this ability. We sell off graveyards and think nothing of it. We embrace fundamentalism over anything else and police to extinction any expression of local beliefs that demonstrate spiritual life. We still drink cerassee tea, sage tea, and lemongrass tea, yet we ignore the spiritual side of this. Or, at least we say we do.

All of the above sayings had and have very deep roots in Afro-Bahamian spirituality. In some communities, it remains a practice for the dead to be buried either the day they die or the day after they die, disregarding the arrival of relatives from far and wide, recognizing the local culture and lore that made it a community even where bodies were washed and prepared for burial by kin, not embalmed, and the passage would be intimate and spiritual. In Cuba, as with many other locations, when a person dies, the body is quickly laid to rest. In Santería, it usually occurs in the first day, much like in Judaism, in many branches of Islam and in some, especially Catholic, Christian churches. Death is not only celebrated, but embraced, because without death, there can be no life.

In the painting “El Velorio” by Francisco Oller, the process of celebrating death is demonstrated in the Museum of the University of Puerto Rico. Nicolás Guillén and Celia Cruz were two famous proponents of Afro-Cuban spirituality, along with Fernando Ortiz, who wrote about it often, they brought spirituality to the world. In Exuma “The Obeah Man” was celebrated and Maureen Duvalier was loved. Both these entertainers sung of Obeah, and spirituality. Does singing it make it less real and more acceptable?

Today, our connection with spirituality seems far more distant that it was in the past, as fundamentalisms set in and further obfuscates its important, the overlaying of mainstream religion that denies the existence of any spirituality. Where there is life, there must be death, there is always a balance. We have become consumed with scapegoating all African-derived religions as bad, evil, dark, black.

When the freed Blacks from the Americas, the enslaved Blacks from other places and the Blacks born into slavery managed to sit with their own thoughts, their spirituality was incredibly dynamic. The dynamism of Bahamian spirituality, it must be underscored, occurred in opposition to all efforts to control/kill it. Junkanoo, was, and perhaps, for some, remains a very spiritual practice. Drumming, dancing, ‘gyrating’ can all be profoundly spiritual practices.

Yet, Exuma can still sing ‘Damn fool ya married to gallin” and explore the whole Obeah aspect of that tradition. The dismissal and simultaneous embracing of spiritual is intriguing. However, the doubled-consciousness of denial of any ‘Blackness’ is even deeper. The absolute disavowal of Blackness is alarming. We so often hear that arts should not celebrate the post ‘40s or the ‘30s or we focus too much on the creation of Black nation. Yet the creation of the Black nation has also led to the death of much Black culture.

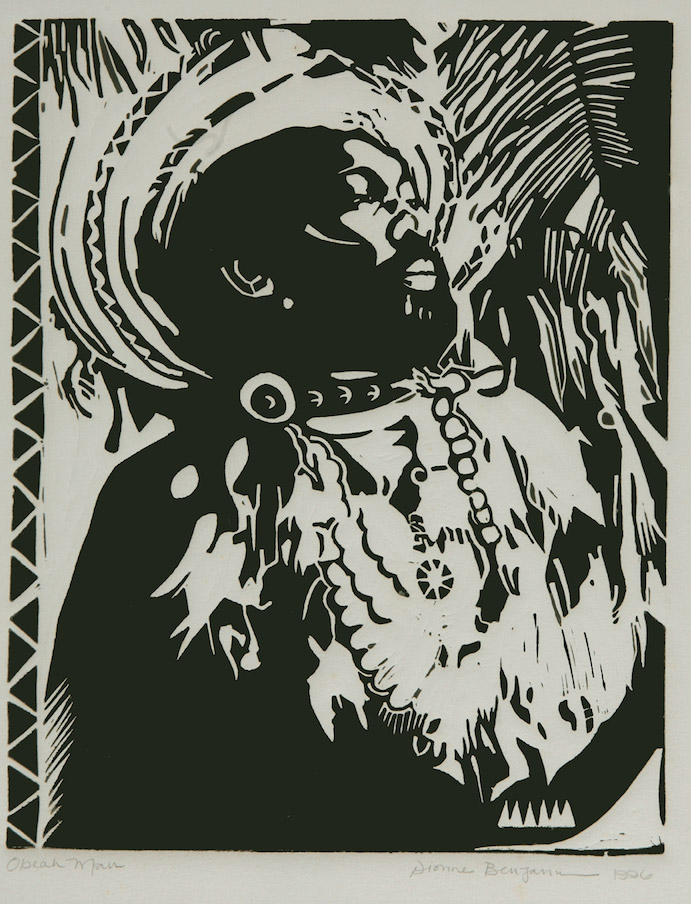

Dionne Benjamin-Smith. “Obeah Man.” Several of Benjamin-Smith’s works will be featured in the upcoming exhibition “Medium: Practices and Routes of Spirituality and Mysticism” on view at the NAGB from December 14th. Image courtesy of the Dawn Davies Collection.

Not a great deal of work has been done on spirituality in The Bahamas; more work has been done on it in the Anglophone region and a massive amount of research and discussion has been centred around spirituality in the wider Caribbean, including the Spanish, French and Papiamento territories, not to mention the circum Caribbean or the Atlantic world.

The arts and artistic practices are uniquely adept at discussing spirituality and expressing it in the national discourse, however, the hegemonic discourse continues to silence its presence. It is interesting, though, that E. Clement Bethel’s The Legend of Sammie Swain (1971), can be performed without repercussions, in this deeply anti-Obeah space.

J. Handler’s and K Bilby’s Enacting Power: The Criminalization of Obeah in the Anglophone Caribbean, 1760-2011 (2012) states:

“In general, the more substantive portions of anti-obeah laws suggest that early West Indians sought the help of obeah practitioners for many of the same reasons that their descendants do today. This said, there is no denying that obeah is widely invoked today in the West Indies to explain evil happenings or bad luck, although the frequency with which it is invoked as an explanatory device for misfortune varies from society to society. Nonetheless, despite the negative views of obeah expressed by many contemporary West Indians and the fact that obeah is still criminalised in most territories, practitioners continue to be sought out-to varying degrees in different societies-for help with a range of life’s problems.” (p. 27)

The setting up, the wake, El Velorio, in Jamaica the Nine Nights ritual, in many Catholic homes reciting the Rosary for a specified number of days and then the special mass after death, the use of yerbabuena (mint) or abrecamino in daily practices, our traditions and practices around death, birth, loss, love and life, are all a part of our spiritual life, our spiritual selves.

It is important to rethink the double-consciousness articulated by critics such as Paul Gilroy in The Black Atlantic (1993), that re-postulate Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Mask (1967) in a modern way, to allow us to no longer disavow our Blackness, to be able to celebrate every aspect of who we are as a people, because the Caribbean as Martí articulates and Antonio Benítez-Rojo later intones is criollo or mixed, and it’s a rhythm that repeats up into New Orleans, Miami, New York, all of which can be seen as Caribbean cities.

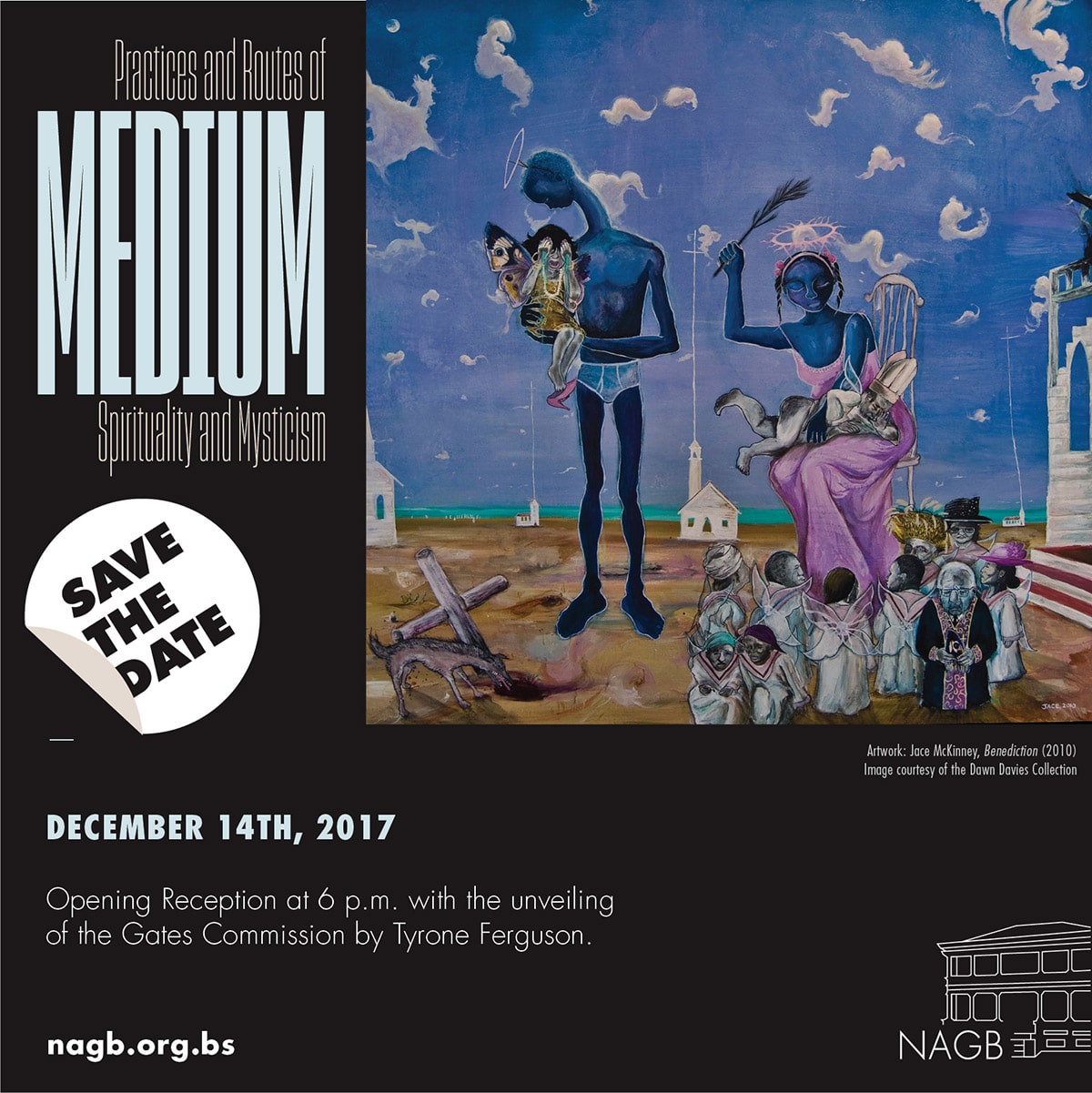

Medium opens on December 14th at the NAGB.

Their spiritual practices and understandings are still actively alive. Perhaps a great lesson in the mixing of everyday life and spirituality is provided in “Girl” (1978) a rudimentary lesson in life from Jamaica Kincaid:

“this is how to make a good medicine for a cold; this is how to make a good medicine to throw away a child before it even becomes a child; this is how to catch a fish; this is how to throw back a fish you don’t like, and that way something bad won’t fall on you; this is how to bully a man; this is how a man bullies you; this is how to love a man, and if this doesn’t work there are other ways, and if they don’t work don’t feel too bad about giving up; this is how to spit up in the air if you feel like it, and this is how to move quick so that it doesn’t fall on you; this is how to make ends meet; always squeeze bread to make sure it’s fresh.” (Excerpt June, 1978, The New Yorker.)

Perhaps “Medium: Practices and Routes of Spirituality and Mysticism”–which opens on Thursday, December 14th, at 6pm featuring the work of 33 artists and remains on view through March 11th, 2018–can begin to break the gravestone imposed over so much of Bahamian culture and spirituality. We must begin to (re)learn or to re-member how to ‘sit with our bones.’

1. Henay, C. (2017) Sitting with My Mother’s Bones. In Dannabang Kuwabong, Janet MacLennan and Dorsia Smith Silva (Eds.) Mothers and Daughters. Bradford, ON: Demeter Press, pp. 65-87.