By Natalie Willis

They may appear to be things of fantasy, with their glittering feathered wings, beads, embellishments, and horns adorning those who look to be less than the usual hooved suspects, but Lavar Munroe’s “Specimens” series find their footing in the real world through their presentation, and indeed through their representation. By investigating through fantasy and myth the repercussions and implications of the waves of colonialism on this landscape, first with Columbus, but also alluding to British colonialism with the museum-style classifications and taxonomies of these fair and strange imagined beasts, Munroe’s “specimens” give us a moment to really think beyond the horrific impact on humans and into the broader ecology of The Bahamas.

The “specimens” were shown first as part of the wider “Invasions” series, including again fantastical drawings and mixed media works, which looks to the “discovery of the New World” with Columbus and the subsequent decimation of the indigenous peoples–Arawak, Lucayan, and Taino–populations in The Bahamas. We have since found promising research that suggests they were not completely eradicated from this place. Through study of other Caribbean island populations near us, the recently uncovered jawbone of an Arawak woman found in Preacher’s Cave, Eleuthera – a thousands-year-old mouth which due to its preserved state is capable of telling us the first full human genome – shows that Caribbean people still hold the DNA of the Indigenous peoples of this chain of limestone and volcanic rock. It would, of course, be arrogant to think that strangers coming to the land that was home and sacred to the Arawaks, could know this landscape intimately enough to know all of its secrets, its hidey-holes, its places of refuge. Of course, the indigenous people’s couldn’t have entirely been killed off, even with disease – they were nomads and resilient and found a way to continue, albeit differently. However, what of the fauna and flora?

Since the West’s “discovery” of the New World, and especially since the British colonialism of the 1800s, the world has seen a sharp decline in many of its species. This is not simply due to the rising numbers of people; it is because our attitudes toward land use and wildlife are changing along with our growing populations, and so much of it is rooted in these key moments in our history. Regardless of when you might wish to date the start of the Anthropocene, it is undeniable that we live in an era where the planet has been forever marked by human intervention. The story of our own changing landscape is being told next door to the Villa Doyle, in our ever-growing native plant and sculpture park, while Munroe’s specimens in the gallery, contained in their shadow-boxes with taxonomic labels carefully laid inside, speak to the western world’s obsession with “discovery” and with taking exoticised treasures “home” to the mother colony.

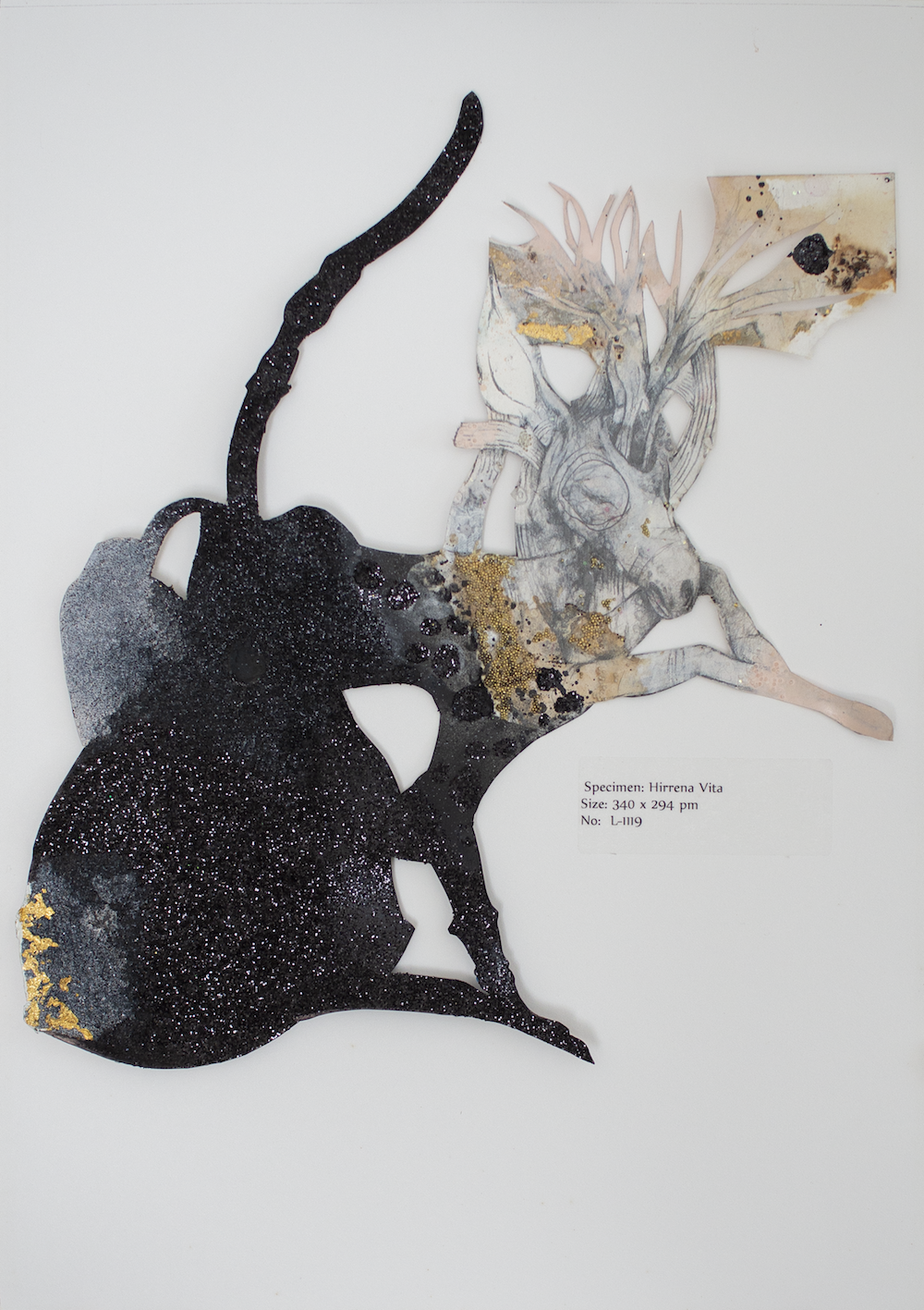

However, how does one who is already exoticised, as Munroe is as a Bahamian, begin to imagine what that exoticism could look like from his perspective? Fantasy and myth are the next best thing, and he mixes this science with alchemy to give rise to these Jurassic Park-cum-Middle Earth beings. Munroe’s “Specimen L-1119” (2011), listed in-image as “Hirrena Vita”, is a visual metaphor of sorts for our effects as humans on the environment, and, more personally, on the land that serves as our inheritance as Caribbean people, as earthlings. The glittering black that is subsuming this creature that is part faun, part rabbit, mimics some voracious, all-consuming virus eating away at its host. Can we look to ourselves and our impact on the planet, in contemporary and historic times, and think “Is this the legacy we wish to leave as people? As a species on this planet?”.

Always the “trickster”, Munroe draws us in with the near-nostalgic, mystical, magical beauty of his works, and leaves us feeling harrowed by its implications. But, after all, honey makes the medicine a little smoother to go down, and this is indeed an easy one on the eyes if not on the heart.