All posts tagged: NE9

Push Out: Jodi Minnis and Ian Bethell-Bennett Investigate the Mythologies and Futures of Gentrification in Over-the-Hill

Essay Push Out: Jodi Minnis and Ian Bethell-Bennett Investigate the Mythologies and Futures of Gentrification in Over-the-Hill Natalie Willis ·

Leaning on your community to create: Natascha Vazquez speaks on her first time National Exhibition

The National Exhibition 9 (NE)9) – An Opportunity for Reflection Part 2

The National Exhibition 9 (NE)9) – An Opportunity for Reflection Part 1

When We Are Like the Trees

Stories When We Are Like the Trees Letitia Pratt · 18 February 2019 “You who are so-called illegal aliens must

Blank Canvas with Cydne Coleby and Letitia Pratt

Women continue to populate the Blank Canvas studio tonight to discuss their artwork and the concepts it addresses in this year’s National Exhibition “NE9: The Fruit & The Seed.”

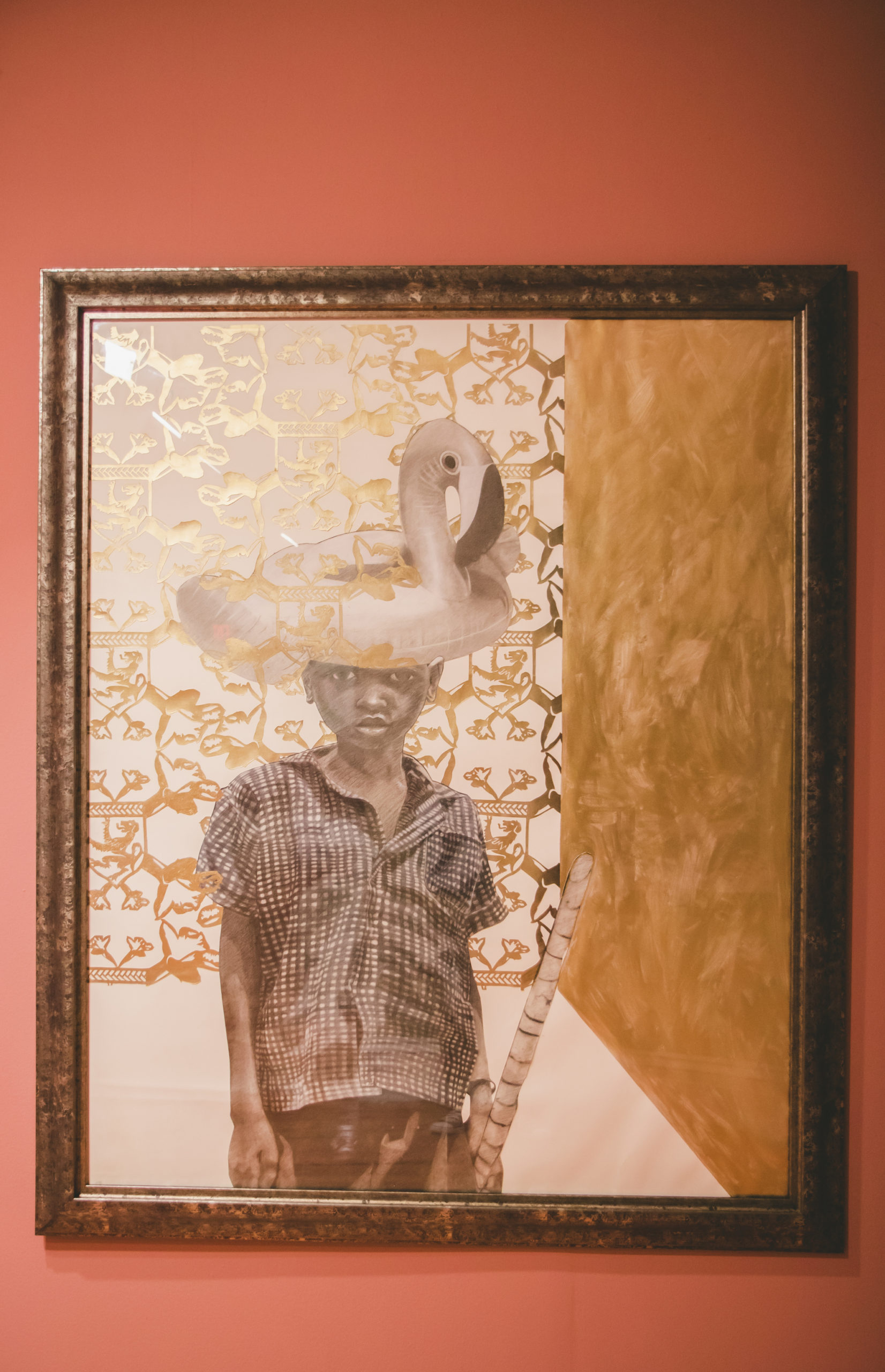

The Island Repeated: Toni Alexia Roach’s Patterned Approach to Confronting the Past

We repeat—limestone, faces, power structures, the same images of palm trees and beaches. Toni Alexia Roach’s work in NE9: The Fruit and The Seed questions these ideas of the Caribbean picturesque.

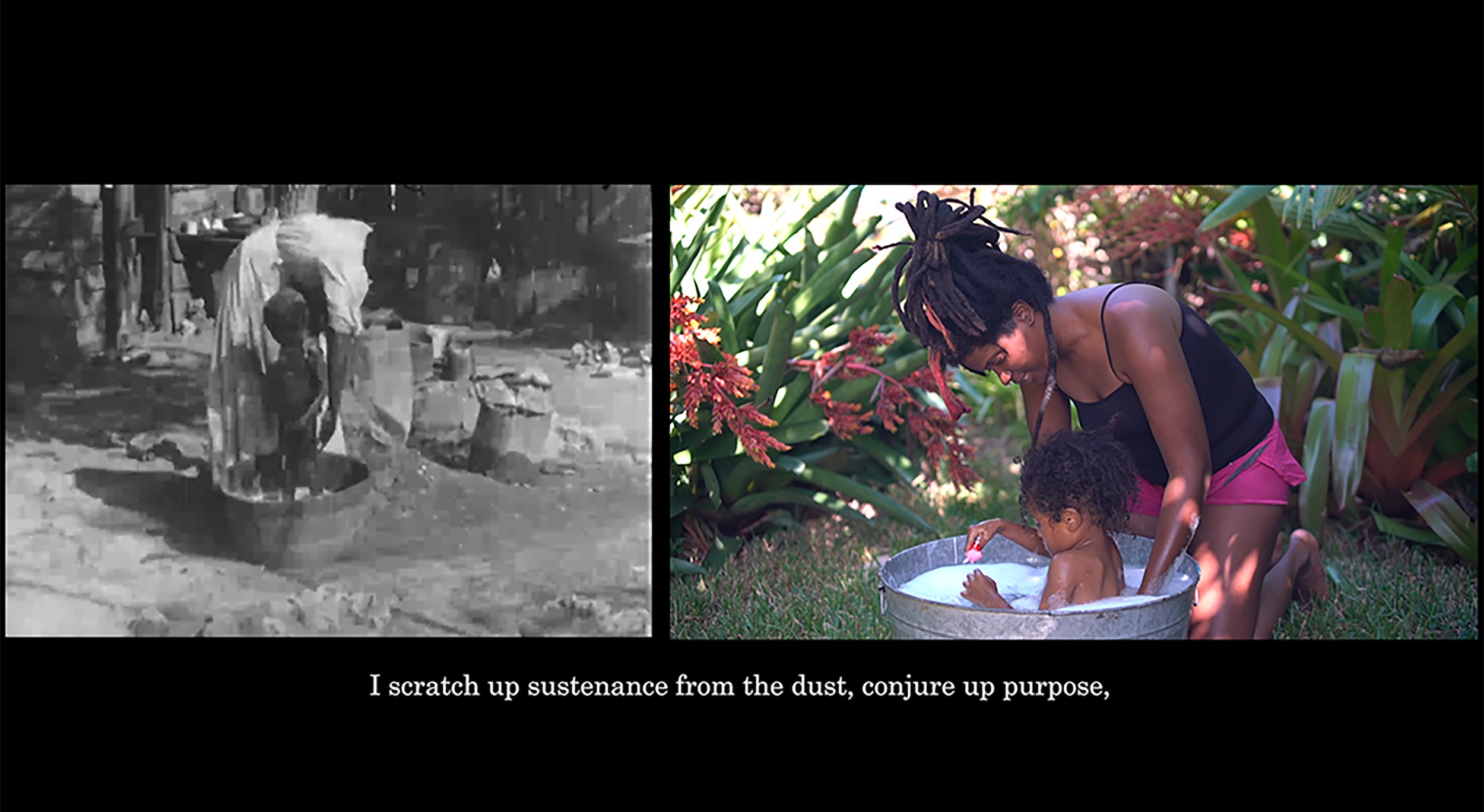

A Botanical of Grief: Yasmin Glinton and Charlotte Henay Connect with Ancestors’ Voices and Put Mother Tongue to Poetry

By Natalie Willis. In much of cultural studies, the Caribbean region has been discussed as a place where people feel an uneasy, tense tie to landscape due to our history of people being displaced here. Paradise or purgatory, whether these islands were viewed as restorative or a place of exile – and truthfully, we have had both stories ring true throughout time, it’s all in the branding. Tourist narratives aside, this space is a difficult one to feel truly close to, the landscape feels at once that it is ours and that it is without of our reach given the fact we are all “from elsewhere”, as Stuart Hall (the late Jamaican scholar and father of cultural studies) stated. Poetry in visual art can also be a difficult fit – is it language? Is it visual? Is it both? Problematising our ties to the land and the neat boxes that traditionalists might wish to shove the vast world of poetry into, are the unapologetic works of Yasmin Glinton and Charlotte Henay. “A Botanical of Grief” (2018), displayed in subtle silver script bearing powerful words of great weight, exists between – like so many of us in the Caribbean. The work is between voices: of the authors, of their ancestors, of poet and of artist, but it also exists in a liminal space physically as it spans the high walls of the stairwell of the 1860’s old bones that make up the Villa Doyle. Stairs are between places, and so are we as children of the Caribbean. We are between Africa and Europe, between India and China, we come from Arawaks, Tainos and Caribs with difficult access to those mother tongues – and most importantly, we are an amalgam of any and all combinations of these continents.

To Heal We Must Remember: Katrina Cartwright’s power figure uproots the past

By Letitia Pratt. It is a hopeful mission of the African diasporas to heal the ancestral pain that Black peoples have inherited. This healing will only come to us in the process of remembering. One of the primary ways to initiate this process is through the creation and consumption of art, which invites us to remember the past, take stock of the present, and come to terms with the complex histories that influence our current experiences as Black people. This process is especially needed for Black Bahamians, whose past traumas shape how we view ourselves. It is incumbent on our ability to tell truths about our past: we must recall times of slave rebellions, punishments, uprisings and revolts. We must remember the slaves that escaped the tyranny of Lord Rolle of Exuma – only to be recaptured and severely punished – and remember the tragedy of Poor Kate of Crooked Island who died from torture in the stocks for seventeen days. (The Morning Chronicle, 1929). It is these stories we need to remember. These are the stories that shaped our ancestors. These are the traumas we need to heal from. Katrina Cartwright’s Nkisi/Nkondi Figure: Prejudice is the Theory, Discrimination is the Practice, (2012) does just that: It forces us to remember, and it inspires us to heal.