By Keisha Oliver.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Irma’s devastation, as the Caribbean recovers and rebuilds, it would be remiss not to pause and reflect. In moving forward, there is much to be considered from our survival and journey as an island people. Our social and physical landscapes have and will continue to weave the rich cultural fabric of our existence once we continue to value and preserve them.

Following the most powerful storm seen in the Caribbean, desecrating islands and leaving many homeless, much debate concerning our built environments has emerged. Largely influenced by environmental factors, Caribbean architecture, dating back to the Lucayans, has responded pragmatically to geography and climate considerations. Even when modelling after the early European trends, which often proved less appropriate to the tropics our structures have still withstood hurricane and storms for decades.

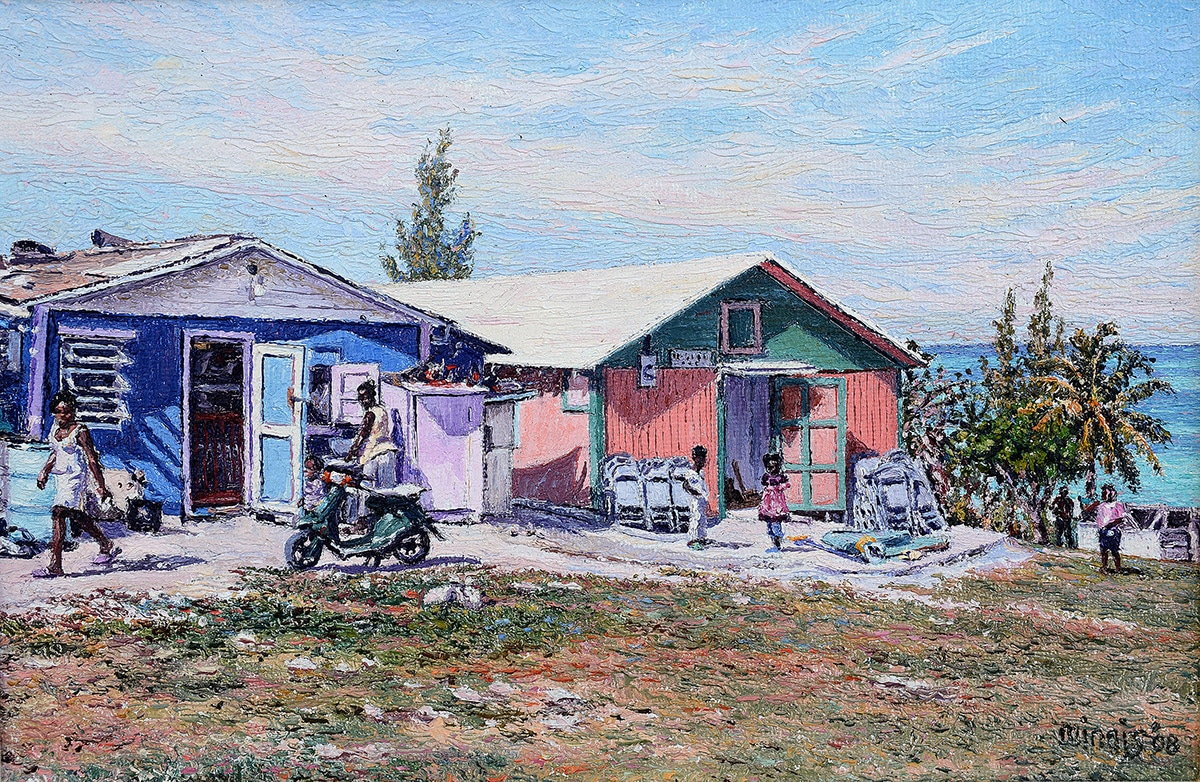

“Out Island Scene” by Eddie Minnis, oil on canvas. 2008 (Photo Courtesy of The Central Bank of The Bahamas)

According to Bahamian Architect and Partner at TDG Architects Marcus Laing, “Building codes and standards in The Bahamas ensure that structures are designed to take wind speeds of at 150mph. The house I grew up in Englerston was a modest two-bedroom home that survived many hurricanes because it was built up two feet from the ground and followed this building code. In fact, clapboard or wood framed house could be just as strong as a concrete block structure. It’s just a matter of the quality and frequency of wood used.”

Although deemed structurally comparable to concrete, clapboard construction is at an all-time low. The once-revered Bahamian clapboard house emerged as an architectural style in the 19th century as one of the most commonly-used styles in the region. Ship-builders turned their woodworking skills to home construction and developed a style that has reached as far as the South Florida area. Sadly, the charming landscape of brightly-coloured clusters that framed our residential communities has left our social and patriotic consciousness. Bulldozed, burned down and belittled has been the fate of the remnants of the clapboard house legacy. Their scarcity is heartbreaking. We’ve abandoned them for concrete floors and drywalls, sometimes carrying over colonial accents like decorative shutters, an understated architectural snub.

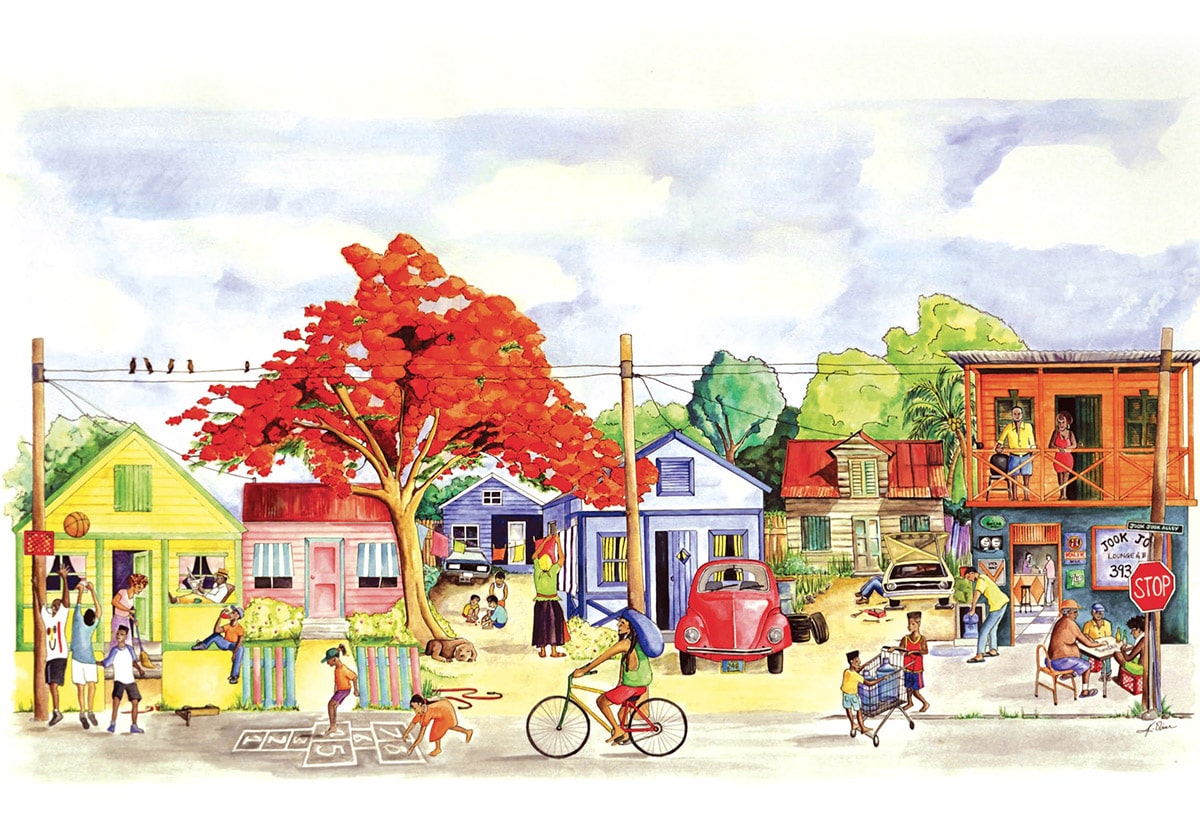

“lsland Homes” By Holston Bain, acrylic on canvas. 1998. (Photo Courtesy of The Central Bank of The Bahamas)

As the Southern Bahamas prepares to rebuild our lost communities, we are presented with a unique opportunity to help reclaim and restore cultural, environmental and possibly economic balance through architecture. Considering the degree and frequency of the threats with which we are faced, it calls for the re-thinking of design, construction and urban planning. This doesn’t mean that we must simply abandon models that have worked for our country for so long, but we should consider realising a blend of preservation, creativity and sustainability that will allow the tradition of the clapboard and similar regional architectural styles to evolve.

According to Assistant Professor in Architecture at University of The Bahamas, Valeria Pintard-Flax, “Drawing a link to our past to the materials and methods used and realising the benefit to a ‘common sense’ approach to building, is essential to moving us toward a more sustainable future for our built environment. I feel that there is a direct correlation of how we build, with an “authentic” traditional lifestyle. This translates not only to the aesthetics of our surroundings but affects how we live. The purpose of architecture is to help people experience the person, the culture and the surroundings; to give a feeling of “authenticity” and “belonging,” a familiarity with the culture and the environment.”

“West Street House” by Nastassia Pratt, watercolour on paper. 2014. (Photo Courtesy of Artist)

Growing up, I have always had a deep appreciation for the endearing and welcoming sense of belonging of tight-knit neighbourhoods in The Bahamas. A community is woven together like a string of clapboard houses, whose landscape appear as a continuance playground, hangout, clothesline and communal space. In 2012, I created a watercolour painting, “Jook Jook Corner,” after returning home having lived abroad for several years, as a way to express this longing that I had for a space I never really experienced. Like myself, many Bahamians will never have the opportunity to know and appreciate the charm of such a space and a time. Thankfully, there is a saving grace. The memory of the architecture and dynamics of the community that lives through the work of visual artists.

Eddie Minnis, many of whose works are in the National Collection, is known for his life’s work of oil paintings that focus on everyday Bahamians in their environment. As a trained architect, there is no surprise that his style is meticulous in capturing the details of the architectural elements. In “Out Island Scene” Minnis offers a glimpse of island life in and around the home with children playing and mothers soaking in the sun as they carry out domestic chores.

“Jook Jook Corner” by Keisha Oliver, watercolour on paper. 2012. (Photo Courtesy of Artist)

Holston Bain and Nastassia Pratt’s work is less about social stereotypes in the Caribbean and are more concerned with architecture and the landscape. The connection between homes and the natural environment not only offer visual references but insightful technical and archival gems. Collectively, these works belong to an anthology of art that can be archived and studied to reference an island people and their habitat.