By : Dr Ian Bethell-Bennett

The post office stands at the top of Parliament Street on East Hill street, a monument to 1970s development. It stands now condemned. The Churchill building stands condemned, much like the Rodney Bain Building on the verge of Parliament Street Hill on the way to the post office. Condemned buildings populate the city of Nassau. The shift has been rapid; from a thriving colonial backwater settled by administrators and Loyalists to a post-colonial shadow of colonial rule, to a derelict city of decay. This shift has been enormous.

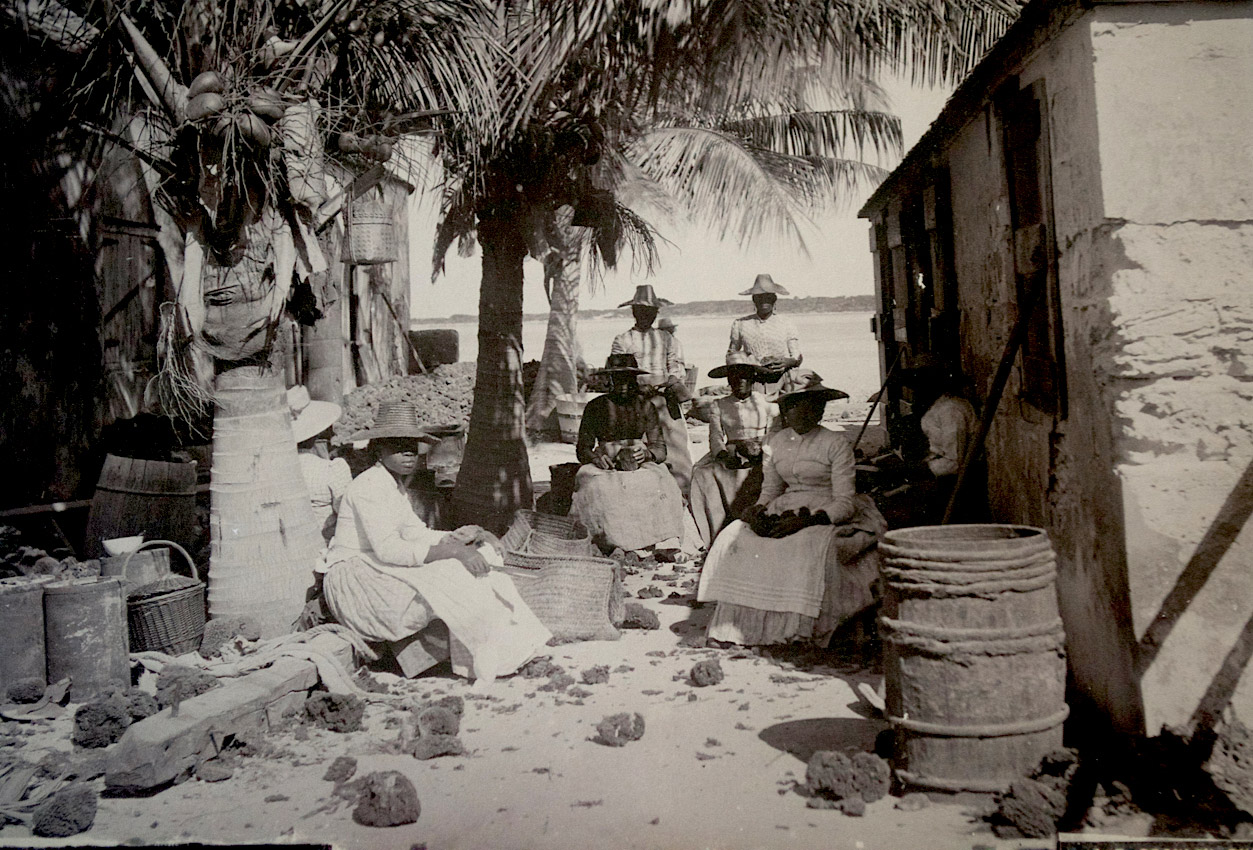

“Sponge Yard” (ca. 1870-1920), Jacob F Coonley, albumen print, 7 x 8. Part of the National Collection, previously owned by R. Brent Malone.

In “An Eye for the Tropics,” (2006) Dr Krista Thompson discusses the image of us created by the power in the centre. It was a romantic notion of what order and beauty should be and this is specially adapted and adopted to the tropics, an idea that had evolved from a dangerous, fecund space to the ordered space imagined into existence where time is suspended and our revelry was allowed for the benefits of tourist enjoyment. This removes attention from the leadership’s exploitation of the masses, as visitors could come and frolic in the tropics and then return home unsullied.

However, the image was always dependent on the imagination and then the space was created to meet that imagining. Nothing was real when the process began. The market woman Thompson described from Jacob Coonley’s work is imagined into being and then her reality is constructed, so that it drives a dream and a particular notion of tropicality. It seems now, in today’s Nassau, that we inhabit a space of tropical dereliction, which also determines how we live and perform.

“A Sponge Yard – Trimming” (ca. 1870-1920), Jacob F Coonley, albumen print, 7 x 8. Part of the National Collection, previously owned by R. Brent Malone.

Space, as Michel Foucault, Edward Soja, and David Harvey state, determines how we live. They make us good people or bad people. The space we live in determines our attitude and our behaviour. Our culture has been determined by the space we inhabit, our space is determined by the natural environment around us. When we live in the space of open gutters, decaying buildings and collapsing roads, we are sent a message that says we are not good enough.

This is especially so when we see on the other side of the road a space of great beauty, high rises, well-manicured parks and open spaces, that butts up against our expectations and makes it clear how impoverished we are, though we may not think about it. This is worsened when those ‘nice’ tropical spaces are seemingly out of reach. However, the irony is not that we strive to be in those spaces, we somehow get trapped in seeing ourselves as undeserving of anything better. We can visit the imagined-into-being tropical space of lushness, but we cannot inhabit that space.

This is particularly so when we are taught to celebrate our oppression as Paulo Freire argues in “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” when he underscores that the oppressed are programmed into being through their education and their treatment at the hands of the oppressor. It is not coincidental that art does not inhabit our Over-the-Hill areas. We have, instead, buildings that are institutional, for the most part, many without running water, electricity or well-maintained roads. The art-filled walls and gardens are missing. The graffiti art seen in other inner city areas is absent here. Art programmes create a culture of creativity; a culture of creativity creates a culture of positive productivity and a space for humanity and self-empowerment and awareness.

“A Native African Hut” (ca.1870 – 1900), Jacob Frank Coonley, albumen print, 7 x 8. Part of the National Collection, previously owned by R. Brent Malone. This photograph was originally printed in “Stark’s History and Guide to the Bahama Islands” in 1900.

When we produce people who inhabit spaces of power and possibility rather than spaces of crime and poverty, we produce development. The space and place for art in these areas and social justice is essential. Art is not simply about pretty pictures. It is about making spaces work for the inhabitants. Art is about design, about building and about mapping and creating the ‘livability’ of spaces.

Spatial justice is essential in any postcolonial community because so much has been decided on before the current leaders coming to power. Maps were made, boundaries drawn and re-presentations affected by the policies of colonial powers who sought to dispossess the population of their land. Edward Said does brilliant work on this. His work informs how we see the imagined and the stereotype and their impact on how we see ourselves. It is also not simply coincidental that governments when attempting to be proactive can be told by special interest groups to leave them alone and let them be. Once the land has been removed from the commons or, in this case, from the Crown, it is about the power to determine how land is imagined and how those who inhabited the land are imagined into or out of being.

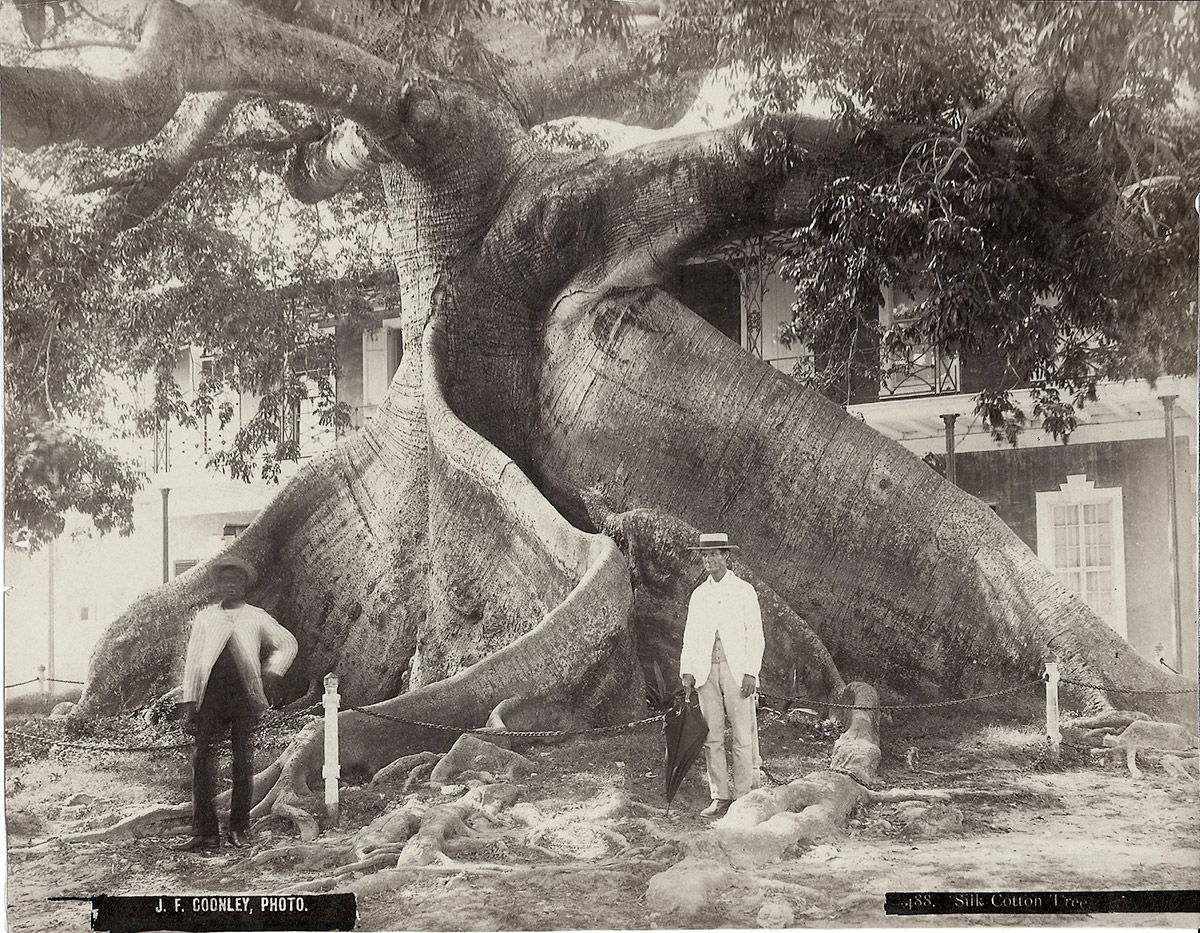

“A Ceiba or Silk Cotton Tree” (1877-78), Jacob F Coonley, albumen print, 7 x 8. Part of the National Collection, previously owned by R. Brent Malone.

Said and Soja both articulate this well. Soja states:

“Colonizing power and the imaginative geographies of Eurocentric orientalism, the cultural construction of the colonised “other” as subordinate and inferior beings, are expressed poetically and politically in defined and regulated spaces. These colonising spaces of social control include the classroom, courthouse, prison, railway station, marketplace, hospital, boulevard, place of worship…practically every place used in everyday life.” (37)

Like the market women imagined into being by Coonley in the heydey of colonialism and re-presentation, we are still being controlled by the idea of where we live and how we live in that space. That “Over-The-Hill” is defined in exclusively negative terms since the end of colonialism, followed by the depopulation of those areas by the then resistance movement, compounded by the removal of art or spatial justice, is telling of how much art can be used to develop an alternative and healthy notion of self and become a tool to empower. We need to work to continue to debunk the image and idea of the market woman and provide professions, careers and self-empowering images that are not limited to the ghetto or life in the service or tourism industry to be of currently seen as unproductive members of this small island.