By Patricia Glinton-Meicholas

“The Fruit and the Seed”, the ninth National Exhibition (NE9), opened at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas on 13 December 2018. As with its antecedents, I celebrated its advent as an asset to much-needed national growth in the creative field. It is essential to trumpet the value of creativity, as it all too often is lost to the cash-on-the-barrel head mentality that afflicts Bahamian society. I congratulate the director, the chief curator, her team and the judges. A great deal of funding, planning and intellectual and physical effort goes into mounting an exhibition, especially one such as the National Exhibition.

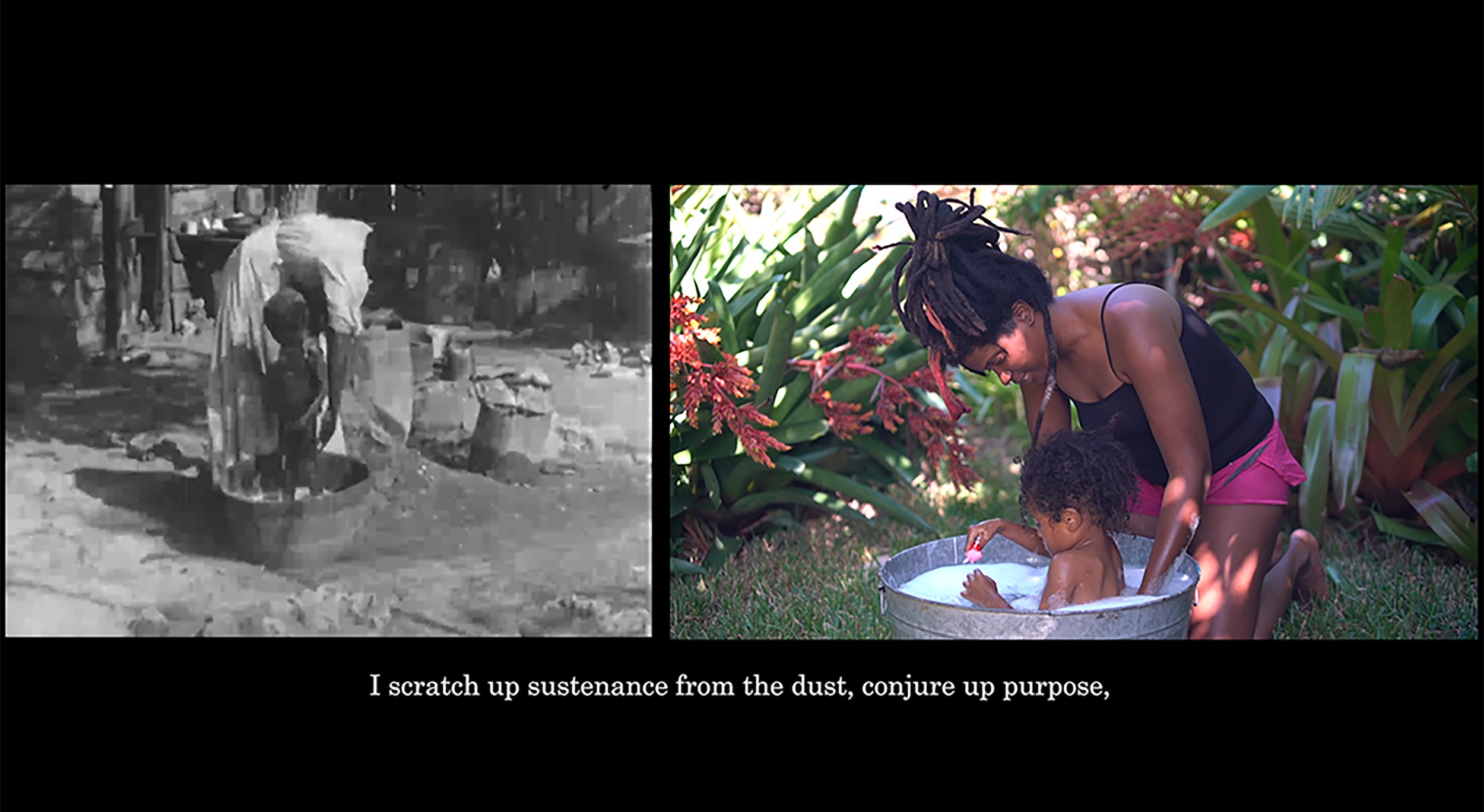

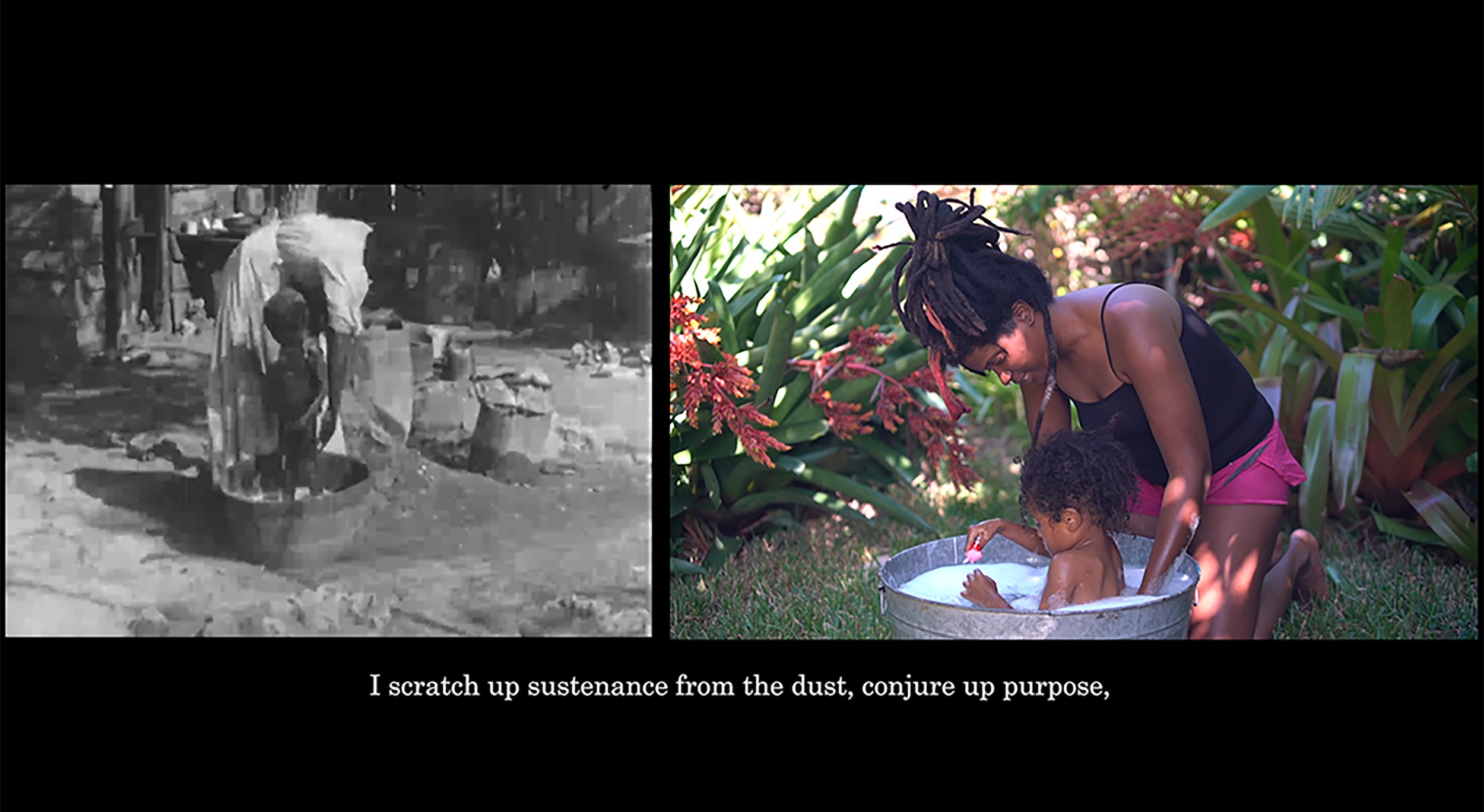

Video still from Tamika Galanis’ “Returning the Gaze: I ga gee you what you lookin’ for” (2018), currently on view at the NAGB as part of the 9th National Exhibition “NE9: The Fruit and The Seed”. All images courtesy of Jackson Petit and the NAGB.

Above all, I celebrated the fact that as many as 38 people took the risk of exposing their works, performances, ideals and sensitivities to public gaze. It was a delight to see that so many young people decided to dive into the waters of a national showing. It is a plunge often made risky by undercurrents generated by an audience still in aesthetic puberty and the clannishness and heavy competition for space that is consistent with a fairly small art circle.

In viewing NE9 the day after the hoop-la of its opening night, when the press of crowds and socializing would likely have obscured the artwork, one absence from the artwork was immediately evident. Save for David Smith, the more senior artists of The Bahamas appear generally to have side-stepped NE-9. As several of them, including Smith, have a recognised ability to ally intent and material rendition that is not dependent upon the aid of a fulsome ‘artist statement’, they could have seasoned the pot and sparked a more profound discussion. Perhaps, they removed their overshadowing presence to allow the sun to shine upon and promote the growth of novices. I mourned their absence from this essential organ for self-examination and the expansion of sensibilities that are so vital to a progressive art movement and a more mature national consciousness. The curator’s declared intent to make this 2018 iteration of the National Exhibition a further “incubator, laboratory and site of curiosity” is admirable in this regard.

To the date of this essay, the writings on NE9 had been sparse and had come from members of NAGB staff or others closely connected. It must surely be a matter of concern for the art professionals of the NAGB and all serious art lovers that the Bahamian art community is still young in terms of the output of critical valuation. The Bahamas has several challenges in this respect. We are a small, insular and mostly euphemistic society. So far, assessments tend to be either overly psycho-sociological to the detriment of the art or superficial, leaning towards non-discriminating. People tend to be non-committal or give favourable views for the sake of acceptance into a circle that is generally considered intellectually and socially gilt-edged and membership within highly desirable. This lack of deep engagement is not useful for the development of artists or NAGB’s advancement.

The 2018 National Exhibition deserves further reflections. I offer what I intend and hope to be critical fertiliser to spur growth of ever-increasing quality in public art in The Bahamas. My point of departure is the curatorial essay, which launched the call for entries to the exhibition. This writing contained a series of questions published to guide the artists’ creation of the works they would submit to be considered for inclusion:

- How are you diversifying your experiences and thoughts through art?

- What language/devices are you using to speak about (re)presentation?

- How are you unfixing colonial understandings of our society and decolonising your space with new ideologies and narratives?

- How do these new images, writings, movements or selves look and where are they located?

- How are you working with The Bahamas’ vulnerable geography to advocate for the environment?

- How are you encouraging your colleagues and peers in this creative ecology?

- How are you defending and protecting those that continue to be stateless?

- What do the paths of resistance look like in your lives, your families, communities and the expansive country?

- How are you making space for yourself and for others that share differing perspectives?

- How does intersectionality benefit yourself, your communities and country?[1]

On my first visit to the NAGB, my reaction was that NE9 had produced a strange harvest. It was my view that the call document had probably cast too wide a net, which led to a degree of thematic incoherence. For the most part, the works and the exhibition title and focal points seemed wildly divergent. Where there should have been a tight bond, these two vital elements seemed not to “hang together”. The offerings of the show were dominated by the works of artists who appear to be neophytes, which may have added to marked discontinuities. It is clear that the curator’s laudable ambitions were located a few floors beyond the reach of the analytical and aesthetic elevators of several of the participants. So much so that some inclusions seem gratuitous.

North Eastern room of upper galleries of NAGB with the works of Cydne Coleby.

With a second visit, I realised that the many of the works were responding to Chief Curator Holly Bynoe’s question “How are you unfixing colonial understandings of our society and decolonising your space with new ideologies and narratives?”. Subsequently, I discovered a phrase—“reclamation of self-representation”—in the statement of exhibitor Tiffany Smith, which provided a kind of Rosetta Stone for understanding what turned out to be the strongest works of 2018 artistic crop.

I have reason to be humbled and honoured that Tamika Galanis chose to use my poem “Woman Unconquerable” as her point of departure and dedicated her submission to me. The film installation turned out to be the star of the show in terms of a deeply reflected conception and artistic realisation of intended meaning. Return of the Gaze: I ga gee you what you lookin’ for (2018), spoke of much archival research and ability to create impressive metaphor, which elevated it out of the common herd. I was taken by the more than century-old film clips from the great American inventor Thomas A. Edison, which are demonstrative of the invasiveness of tourism and key to Galanis’ message. In the gaze of the tourist, the indigenous people and their culture were little more than spectacle, which the visitor could sample at will, without permission and invading a most basic right and space. Filmed in four vignettes, Galanis attempts to recreate Edison’s scenes with women casted to radically contest the colonial/tourist’s point of departure as privileged spectator. Her message is ownership of oneself and one’s culture and sole right to self-definition, which is worthy of vigorous defence.

The first three tableaux of “Return of the Gaze: I ga gee you what you lookin’ for are highly successful in this regard. In the first, a woman threatens an unseen voyeur with a machete; in the second the woman bathing her child removes the toddler from the unwanted intrusion, shielding its body with her own in a frantic departure. The sexually explicit dancing of the woman featured in the third vignette profoundly underscores the subtitle of the Galanis’ work I ga gee you what you lookin’ for. In turning and shaking her “boonggy” to the camera, she is exhibiting an iconic Bahamian gesture of contempt.

In something of a departure—an upping of the decolonising ante—the fourth Galanis vignette focuses on the take-over of Nassau’s most colonial space—the city-centre Parliament Square with its dominant statue of Queen Victoria surrounded by more than two-hundred-year old Parliament buildings of Georgian architecture. Here is the most visible remnant of the pre-independence era, of which the principal ethos was the subjugation of the indigenous people, ritual, value system and landscapes. The Square can be taken as an egregious contradiction of independence and self-definition. If this vignette has a weakness, it is that the unfolding relies too heavily on the viewer’s ability to recognise the artefacts of African-descended ritual. The question arises as to whether an exploration of the post-colonial landscape of women with vignettes of actual daily life might not have better served the artist’s purpose.

It is hoped that Galanis will extend this work to explore whether or how the socioeconomic ecology and perception of Bahamian and Caribbean women have changed over the hundred years.

[1] (https://nagb.org.bs/mixedmediablog/2018/7/9/ne9opencall)

Part 2 of An Opportunity for Reflection can be found here.