By: Ethan Knowles

A language can do much more than greet and give directions. It can unite or it can incite; it can build and, just as quickly, it can break down. It can change, and it can change. Indeed, entire communities and cultures perch on the tips of common tongues and intonations, and The Bahamas is no different. Here we speak English, united with other Caribbean nations like St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Barbados and Jamaica by a common colonial past. But here we also speak a “dialeck”. Call it Bahamianese or Bahamian Creole, it is a vernacular that harbours our past and permeates our present all the same. And so, the question remains: if a language can do all that, what does a dialect do?

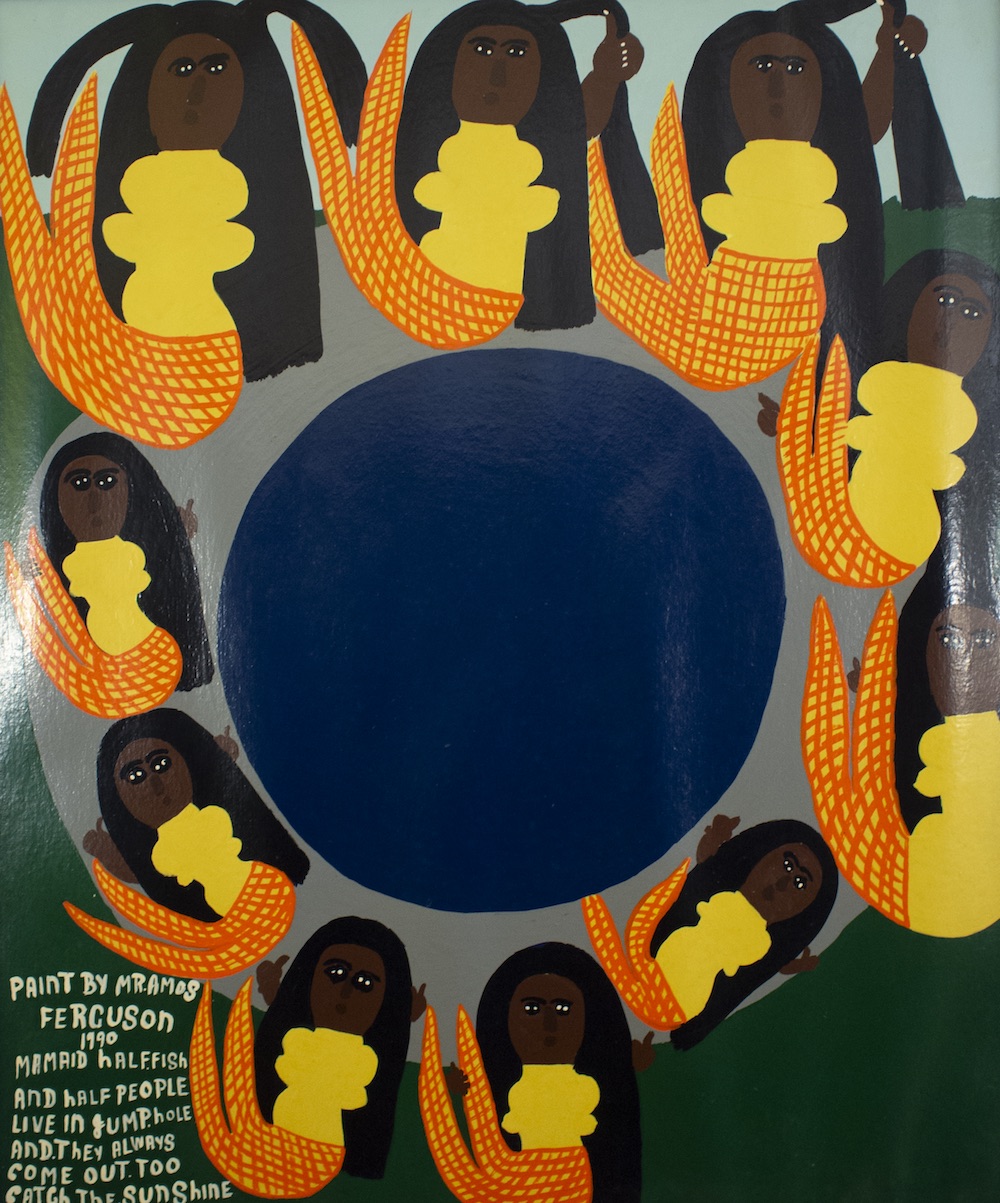

“Mamaids. Half Fish Half People” (1990), Amos Ferguson, house paint on board, 36 x 30. The National Collection.

Curated by Natalie Willis and Richardo Barrett, “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean” deals with just this question. “Hard Mouth” explores how visual and verbal language has molded the sociocultural landscape of our archipelago and considers how, in the wake of a history of revolt and reclamation, we find our voice today. From the ways we express political discontent, to our depictions of women, to our dialogue with our West African and European heritage, the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas’ latest Permanent Exhibition touches heavily on the Bahamian experience, both past and present, and the ways in which language and identity interact within our nation.

Apposite to the overarching theme of language is the work of intuitive or ‘outsider’ artist Amos Ferguson, which can be seen upon entering the exhibition. Born on the island of Exuma in 1920, Ferguson enjoyed a typical out-island childhood replete with farming, fishing and warmly-received religious instruction. Having moved to Nassau at seventeen, Ferguson began working as a carpenter and later would become a private contractor, painting houses for the wealthy. During this period, Ferguson produced some of his early work, but it was not until a nephew approached him with a dream that the painter’s practice began to pick up steam. In the dream, Jesus rose from the sea with a painting and told the nephew that a certain relative was squandering his talents. Shortly after receiving this news, Ferguson would go on to paint his various visions and observations full-time, with whatever materials he had available. It was also around this time that he set up shop on Bay Street, working alongside his future wife, Bea, in decorating handicrafts and developing his style. Though popular with tourists, Ferguson’s work was largely rejected by Bahamians, that is, until two influential women in the United States helped orchestrate a series of solo exhibitions of the Ferguson’s work during the latter stages of his life.

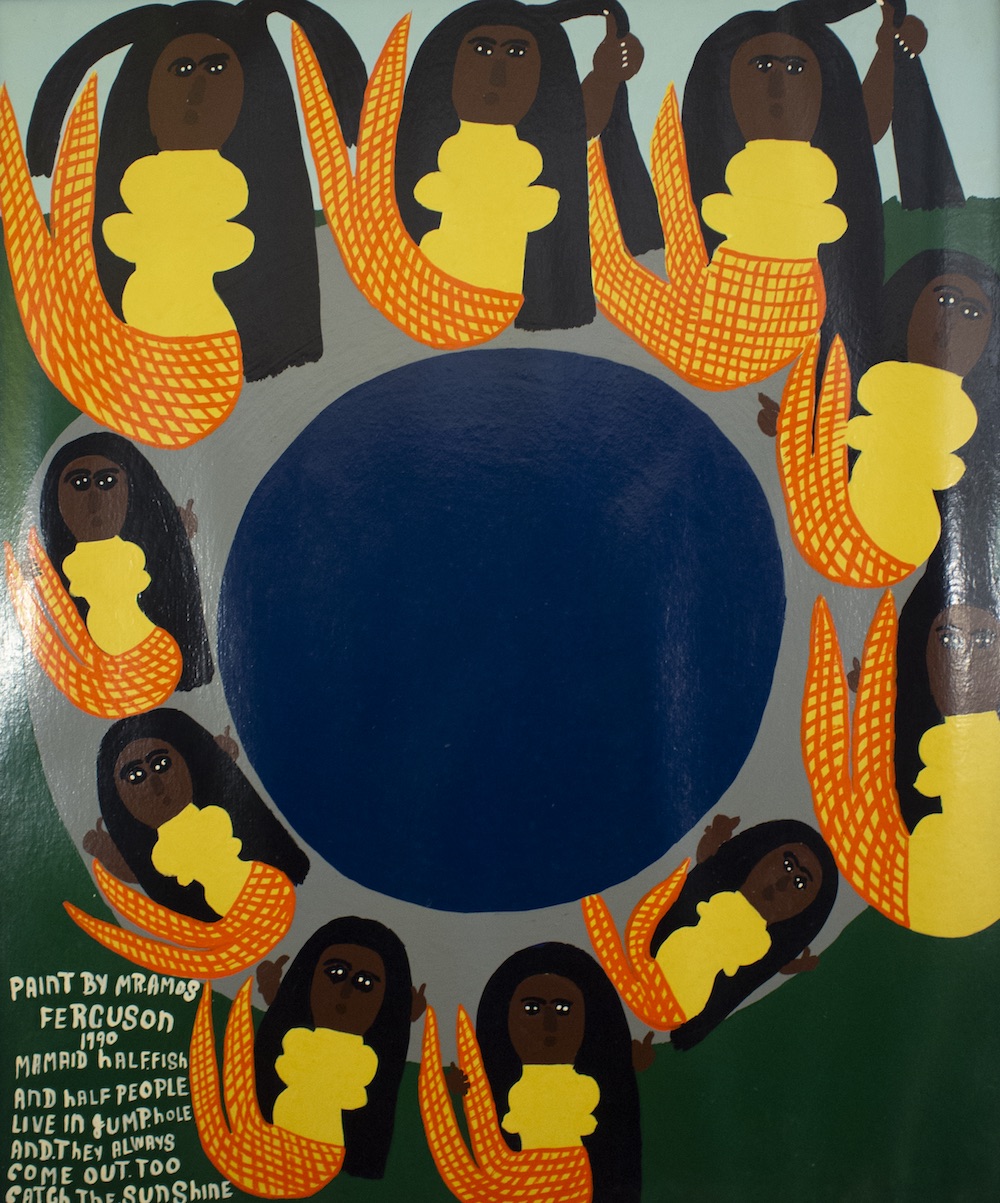

Installation shot from “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean”, the new Permanent Exhibition on view at the NAGB through June 2019.

It’s worth mentioning that the reason Ferguson’s work falls into the category of ‘outsider’ art, otherwise known as folk, naïve, or intuitive art, is not simply because he was self-taught, but because his practice was conducted outside the mainstream art tradition and therefore disregarded many of its conventions. This very tendency to manoeuver outside traditional molds and challenge the pervading narrative of what an artist should be and do is exactly why we have so much to learn from Amos Ferguson. But it is not only Ferguson’s independence from which we can draw wisdom, but also his genuineness. These two facets of the folk artist’s legacy – his autonomy and authenticity – have a lot to offer our spry nation as we cross the forty-fifth anniversary of independence.

In many ways, intuitive art can be viewed as a ‘dialect’ of the wider artistic tradition alongside which it operates. Intuitive art may be deemed less sophisticated, marginal, and even cheap – much like a dialect can be painted as the backward indigent of a mother tongue. Indeed, both can be seen as insolent offshoots of a larger, often more respected precedent, as in many ways Bahamianese is to English, and Ferguson’s intuitive practice is to the Chelsea Pottery tradition of the sixties. At the same time, however, dialects and outsider art embody defiance and autonomy. They thrive at the peripheral level, operating autonomously as tiny pockets of growth and self-development. Like the example that Amos Ferguson illustrates, it is sometimes necessary to break away from existing traditions – even unconsciously so – by independently pursuing one’s own practice, in one’s own space. Though such moves may initially be met by dismissal and condescension, it is essential now more than ever to have such exemplars of eccentricity to lean on.

“The Family Off Eight” (1991), Amos Ferguson, house paint on board, 36 x 30. The National Collection.

Amos Ferguson’s life and work urge us to take what we have, whether within or around us, and use it uniquely for the betterment of both our neighbors and ourselves. Applying such a philosophy to the issue of language, we might then see the need to stop marginalizing our own “dialeck” and instead celebrate it. Yes, celebrate it. Just as Ferguson did in his painting descriptions: champion it as an expression of our identity and a source of our sense of belonging. So, to answer the question of what a dialect can do, I would argue that it constructs a home, and it brings its speakers in by the hand. Indeed, a dialect can unite and build just like a language. But in our case, it can also repossess. It is a method of not only acknowledging our colonial past but of moving beyond and making it our own. Of shaping and molding it to our tastes. Our dialect is no ‘broken’ English, but a reclaimed and appropriated English – a gem in our postcolonial crown.

The life of Amos Ferguson also has much to say on the issue of authenticity. Throughout his career, Ferguson often looked inside himself for artistic inspiration, painting his personal visions from memory or pulling from his religious background. Otherwise, he painted what he knew from everyday life. He painted gospel choirs, junkanooers, and newlyweds. He produced brilliant flora, captivating fauna, and even stunning seascapes – all of which harked back to an idyllic out-island childhood. In capturing the Bahamian experience, Ferguson took a modest yet authentic approach and for this reason, amongst his quirky signatures and idiosyncratic style, enthralled droves of tourists with his art. It should be noted, however, that although for many years foreigners were the principal supporters of Ferguson’s work, the artist would never compromise what he considered his divinely-driven practice. Ferguson painted based on mood, declining to conform his craft to what he thought his visiting clientele sought despite evidently knowing which works sold best. His practice was not an effort to please, but an exercise in introspection. The outsider artist dove down into depths of himself to bring forth treasures we still admire and learn from today.

Installation shot of Amos Ferguson’s work in “Hard Mouth: From the Tongue of the Ocean”, the new Permanent Exhibition on view at the NAGB through June 2019.

Perhaps, as a nation, we would do well to follow Ferguson’s example. As more and more of our number fall victim to an almost manic obsession with the outsider’s gaze, we find ourselves ever struggling to decipher who it is we are, and whether what we do is truly for ourselves, or for our fleeting guests. When we pick up litter off the roadside, do we really do it out of concern for our country’s natural environment? Or are we simply striving to please the tourist eye? The unfortunate reality is that in solely focusing on how we may be scrutinised by others, we risk forgetting experience and be first persons in our own lives – to dig inside and actively develop ourselves. The great ill of tourism, rather paradoxically, is that it so often alienates instead of encouraging the cultural exchange that it should. It distances people from their own heritage by regularly compelling them to view it from the outside, and even worse, to assess its potential for economic exploitation.

Now, more than ever, we must ask ourselves: Are we outsiders in our own land? And if so, can we afford to wait until someone else orchestrates our solo show?