By Natalie Willis

This week we continue our interview with Sonia Farmer on her work for the upcoming collaborative exhibition with the British Council, “We Suffer To Remain”. It is difficult to think about just who gets to discuss our history, when some voices are silenced, and others get a proverbial loudspeaker. Farmer’s artist book “A True & Exact History”, a poem produced from her erasure of Richard Ligon’s “A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes” (1657), deals with just that.

Author and artist, Sonia Farmer.

NW: Given that the exhibition has an underlying theme of slavery and its legacies, how do you begin to position yourself in regards to this complicated history and the vestiges we see of it today?

SF: I’m thinking a lot about what it means for Graham Fagen to make the work he did, and for me to make this work (especially around me being white in the Caribbean space), and what visibility that affords us, and protection too. What does it mean, as a white person in the Caribbean with English heritage, to engage with a white English man’s narrative (Ligon’s), to create a new narrative about the Caribbean space? What kind of interesting bridge is being built there, if it is interesting? How does my narrative differ to that of a Black Caribbean writer exactly–because they certainly would be different. Each erasure is different because we come at it from our perspective, concerns and identity. This exhibition is giving me an opportunity to think about what it means to have made this work.

I was particularly interested in engaging on the level of language and narrative. In interrogating Ligon’s narrative, I think my poem is building a bridge to my position today, and revealing the emotional burden of Caribbean people living in a space that was shaped by so much violence to get to our present day. A large part of that violence is the legacy of slavery in our space. I didn’t go into the project with the intention of interrogating slavery specifically, though it’s so naturally present in the work. But of course, by the act of engaging with this writer, and the powers he had in his time, I am undoubtedly participating in a political, subversive act. Erasure is just that.

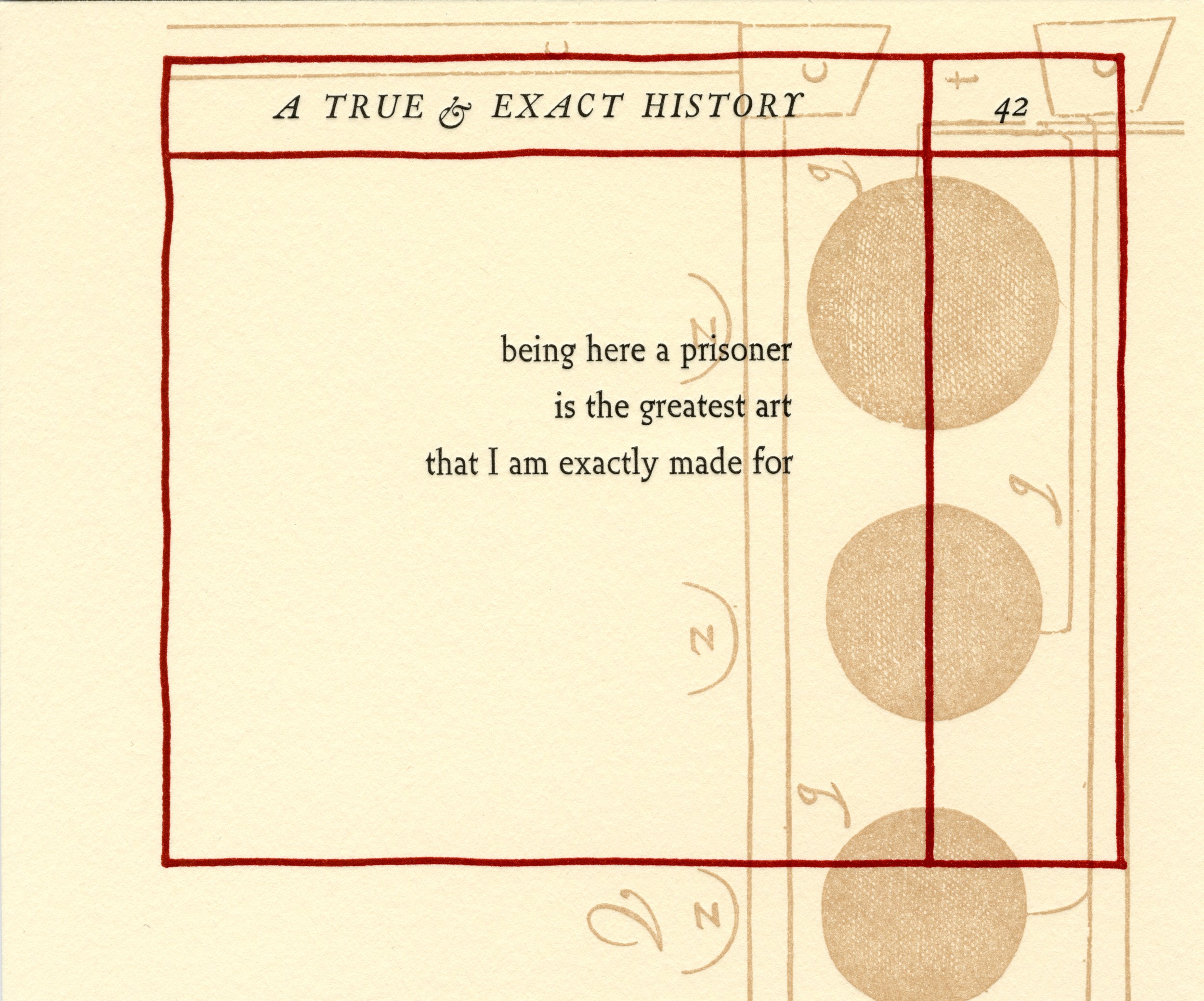

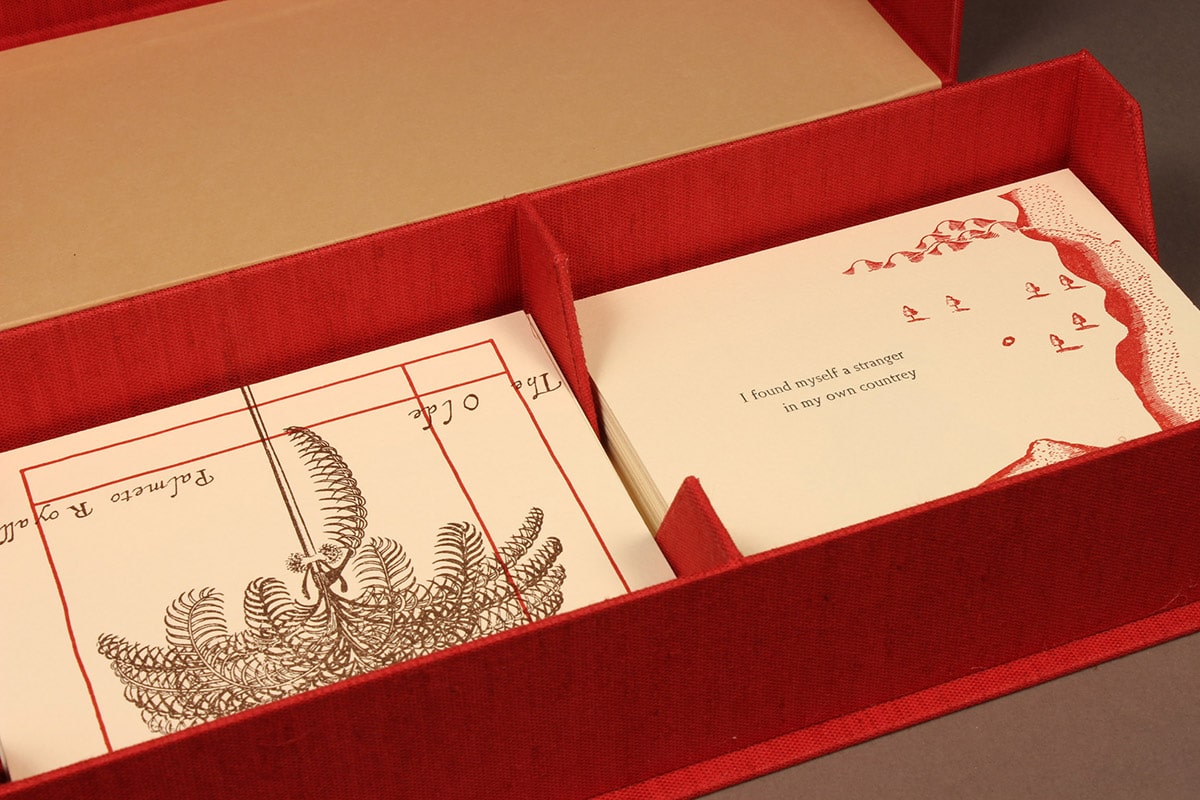

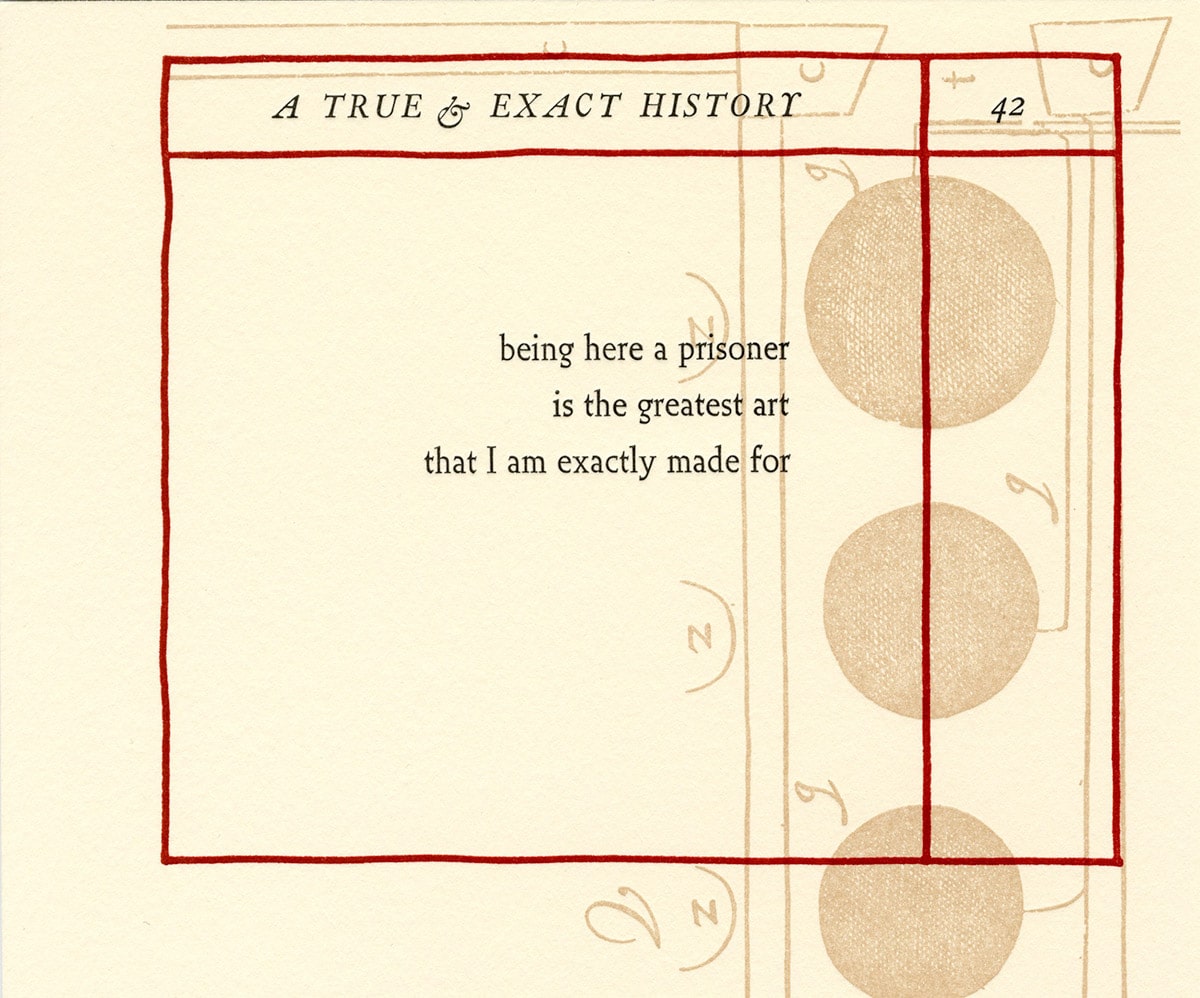

“A True & Exact History” (2018), Sonia Farmer, letterpress printed book, Erasure of Richard Ligon’s “A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes” (1657), letterpress-printed and collected into a handmade clamshell box measured, 5.5″ x 13″ (closed box). Edition of 25. Image courtesy of Sonia Farmer.

NW: In this idea of bridging, tell me more about how your work plays with the quality of time in the Caribbean?

SF: I feel like this piece was produced during suspensions of time. When I started the project, I was at Fresh Milk in Barbados, and I wrote the first two parts there at my residency. That was a period of suspension for me in that I was visiting another Caribbean space. I think that when you’re from the Caribbean but visiting another country in the region, it almost becomes an act of magical realism. You’re in a world you know, but it’s a little ‘off’. You see the signifiers that you recognise as your home, but you also see how things could’ve been so different if you had not been born or lived in that particular part of the Caribbean that is yours. There’s still an underlying Caribbeanness that is familiar, which I think is the history and the violence, and there are other things too, that aren’t heavy. I finished the work in other suspended spaces also: on a train in Iowa, on the Bohengy, and lastly on a bus. All the erasures occurred in these skewed senses of time and place. I feel it was crucial for the raw, first draft of the work and the actual erasure itself to happen in these suspended spaces.

Letterpress print from Sonia Farmer’s artist book, “A True & Exact History” (2018).

NW: Lastly… how do you think “We Suffer To Remain”?

SF: I’ve been thinking about this line it since I wrote it. It comes early on in the narrative, and I believe in my poem it’s the first time we’re introduced to the voice of someone who is on the island Ligon is describing somehow. The voice also says “being here a prisoner, is the greatest art that I am exactly made for”. Those two lines articulate the work of living in the Caribbean space. I say “the work of” because the work that you have to do emotionally just to live in the Caribbean space. It makes us uncomfortable, it’s like we are calling that work into question too much, making people too aware of it, and that’s a problem for us. We feel we aren’t supposed to show “how the sausage is made” or “how the pig feet souse” gets made in the Caribbean.

I think “We Suffer to Remain” taps into the emotional burden of those of us who live in the Caribbean, who do the work of living in ‘paradise’ and what that means in a place where tourism is our primary industry. Not ecotourism or cultural tourism so much as the one-dimensional tourism of sun, sand and sea. They are lovely, beautiful resources – but they are not enough. My next project is interrogating the myth of paradise and who does the making of paradise, the physical making of it. Not the imagination that exists in the mind of the visitor. When I hear that line I think of the people who might not even choose to “remain” in the spaces they create or that they are forced to be creating, especially those people who aren’t aware that they do this work.

Sometimes when we talk about suffering, especially when it comes to women, we think that suffering is something of beauty, about beauty in pain – and perhaps to our detriment. In my piece, and in this line, I think of suffering not as beautiful, but as being acknowledged and visible, because it isn’t usually allowed to do so in the Caribbean.

“We Suffer To Remain” opens on March 22nd at 7 p.m. at the NAGB and is open to the general public. There will be an artist talk on Friday, March 23rd starting at 6 p.m. with participating artists Anina Major, John Beadle, Graham Fagen and Farmer.