By Natalie Willis

“Monumental” is a bit of a slippery word, to say the least. Think “giant towering structures” or the Eiffel Tower, the Burj Khalifa, any number of impossibly big (or big for the time) constructions. Monumental can also mean exactly that, ‘monument’, and as the most recent Double Dutch exhibition, “Re: Encounter” shows, artists can often speak to the idea of the monumental both in size and in content. Dede Brown presents ambiguous humanoid busts, absent and cut out of wood and masonite, which are suspended from the ceiling – perhaps un-monumental in their own way. Playing into this in a different respect, Joiri Minaya presents us with a monumental wall of stretchy fabric that spans the width of the ballroom, but also gives us a series of postcards depicting a proposal for artistic intervention on the Christopher Columbus monument that sits at the front of Government House, making good use of both sides of this double-meaning of the word.

“Proposal For Artistic Intervention on the Columbus Statue in Front of Government House, Nassau” (2017), Joiri Minaya, postcard, 5×7.

The sculpture holds quite an interesting story, really, in light of the recent upheavals this year over problematic sculptures in both the US and the Caribbean in particular, it is good to note that this 12-foot-tall monument to the Italian explorer that ‘discovered’ The Bahamas was in fact gifted to the then-Governor, James Carmichael Smythe, purportedly as a gift by free Blacks to the Bahamian people (the statue of Queen Victoria in Rawson’s Square came later, which is oddly fitting given the history). They had wanted to place the image in Rawson Square originally, but got told to put it in front of ‘their house’ at Government House instead.

The idea of Columbus discovering the islands is certainly a point of contention – how could he possibly “discover” a place that was already inhabited? But then again, this is how the colonial game worked in its first major wave of activity. Though, if I went into my neighbour’s yard and said I ‘discovered’ the house there and took up occupancy and ordered them around, it mightn’t go down so well. And the notion of the statue as a gift (apparently not very well received) is more peculiar still, well, all things in their respective times…

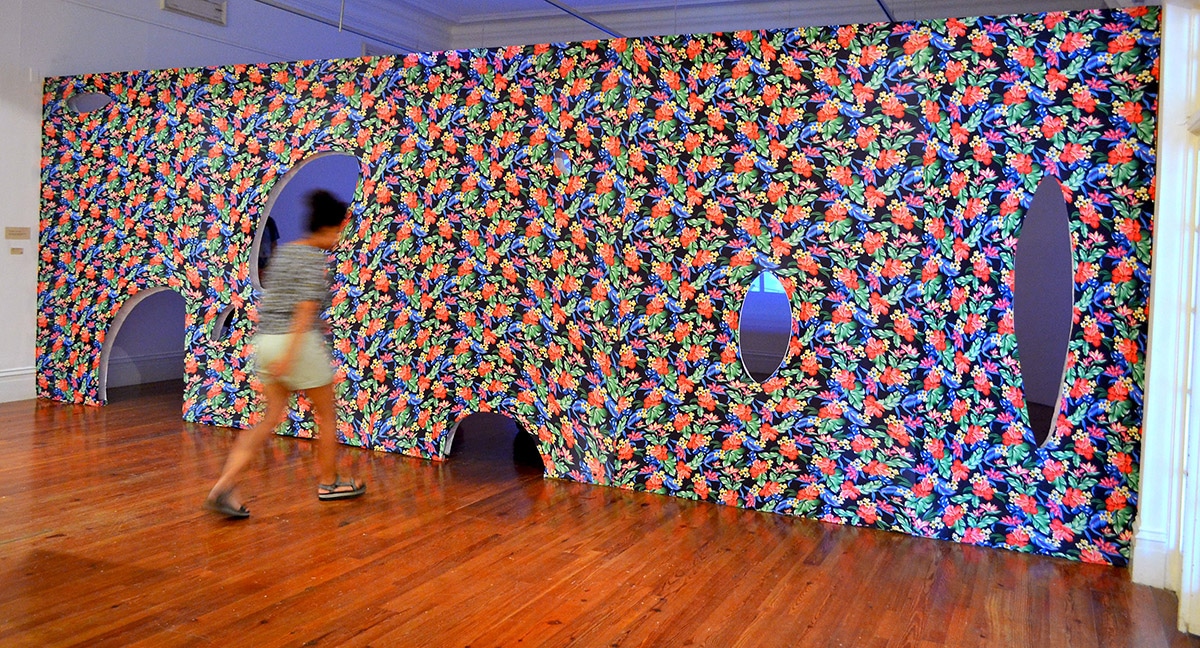

Installation view of “Invitation to Transgress” (2017), an installation work by Joiri Minaya.

All this aside, this key bit of knowledge leaves this monument in rather a confusing state for us: Columbus is representative of part of the reason we feel such a lack of origin in this country (though we cling so tight to our ideas of what Bahamian is, it is by and large based upon displacement) for killing off the Arawaks, Lucayans, and Tainos who lived here, and to add insult to (syphilis and) injury, he paved the way for the most impactful wave of colonial activity with the arrival (see: claiming) of the British. Still, it was, for all intents and purposes, a ‘well-received’ gift, and the practice of ‘re-gifting’ is generally frowned upon, but repurposing a monument might be better suited.

The arguments to have these items preserved as history is fair, they are. The arguments to have them destroyed for what they represent is also fair as they are, in fact, deeply painful for many when they look at these giant structures, reminding them of the instruments of power that lead to the state we are in now. But art offers a shining alternative: re-contextualising. As art generally deals with the past and present in a very visible, tangible way, it makes sense then to have artists do just so: to make sense of these sculptures for us in the here and now, which is what makes Minaya’s proposal so enticing.

Installation view of “Tesselations (Pieces of Me, Pieces of You)” (2017) by Dede Brown

Do we really need to keep these giant reminders in place, completely untouched, to become an antiquated emblem? Could we not simply give them a ‘makeover’ to make them relevant to us in a way that helps us preserve the culture, engage with it, and to help us feel that we have power over these things and our spaces for once in our lives? Monuments themselves are seen as masculine structures, not just because of their scale and the bravado it takes to complete such things, but also because of the phallic nature of sculptures, such as the Washington monument. This often renders them as patriarchal objects, which provides a point of discomfort for many women in feeling a sense of reinforcement of the power men hold in society, not in a dissimilar manner to the way that one might find confederate monuments uncomfortable as a person of African descent. The constant reminder that these old power structures of racial, patriarchal and classist hegemony are very much alive as we feel the repercussions today is exemplified in these statues – a public reminder of who others think you are and your place.

Installation view of ““Proposal For Artistic Intervention on the Columbus Statue in Front of Government House, Nassau” (2017) by Joiri Minaya.

Wouldn’t it be marvelous to take these things, keep them in public view, but shift their context so that we can really dig into some decent discussions on it all, without feeling uncomfortable, whilst looking at some, frankly, cool interventions around it all? The discourse need to be had, and nurtured, in a way that doesn’t make anyone feel threatened or fragile about their beliefs – be they for or against. Perhaps this gesture is a good start.